Haiti gangs: The spiralling power of criminal groups

- Published

Protests against Prime Minister Ariel Henry have been mounting in recent weeks

Thousands of prisoners on the loose after gangs stormed the jails they were in, a government without a single elected official and a gang leader who openly threatens the prime minister.

The scenes unfolding in Haiti are shocking even to those who have been following the seemingly unstoppable rise of armed groups in the country in recent years.

Here we take a closer look at how gangs have come to dominate huge swathes of the capital and, increasingly, of rural areas of this Caribbean country.

Armed groups have long played a bloody role in Haiti's history.

During the 29 years of the dictatorship of François Duvalier, known as Papa Doc, and his son Jean Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier, a paramilitary force called the Tonton Macoutes used extreme violence to stamp out any opposition to the Duvalier regime.

The younger Duvalier was forced into exile in 1986, but gangs have continued to exert varying degrees of power, sometimes shielded and encouraged by the politicians with whom they forged alliances.

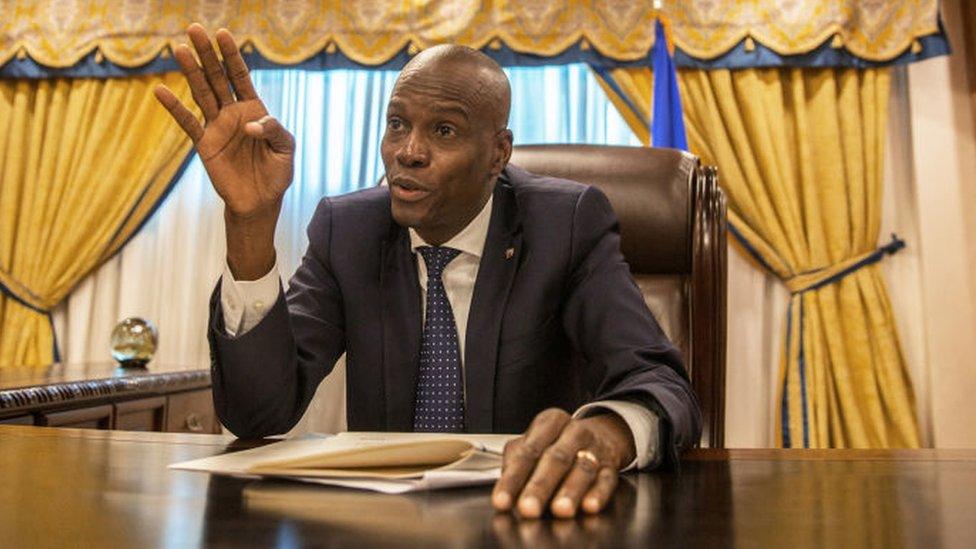

The most recent widespread outbreak of gang violence has been fuelled by the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse on 7 July 2021.

Jovenel Moïse was shot dead in July 2021

The president was shot dead by a group of Colombian mercenaries at his home outside of Port-au-Prince after he had started denouncing "dark forces" inside Haiti.

While the Colombians and a number of other suspects have been arrested, an investigation into his killing has still not determined who ordered the president's assassination.

Gang violence had already been rampant under President Moïse, but the power vacuum created by his murder allowed these gangs to seize more territory and become more influential.

And it is not just the position of president which is vacant.

Following repeated delays to hold legislative elections, the terms of all elected official have run out, leaving the country's institutions rudderless.

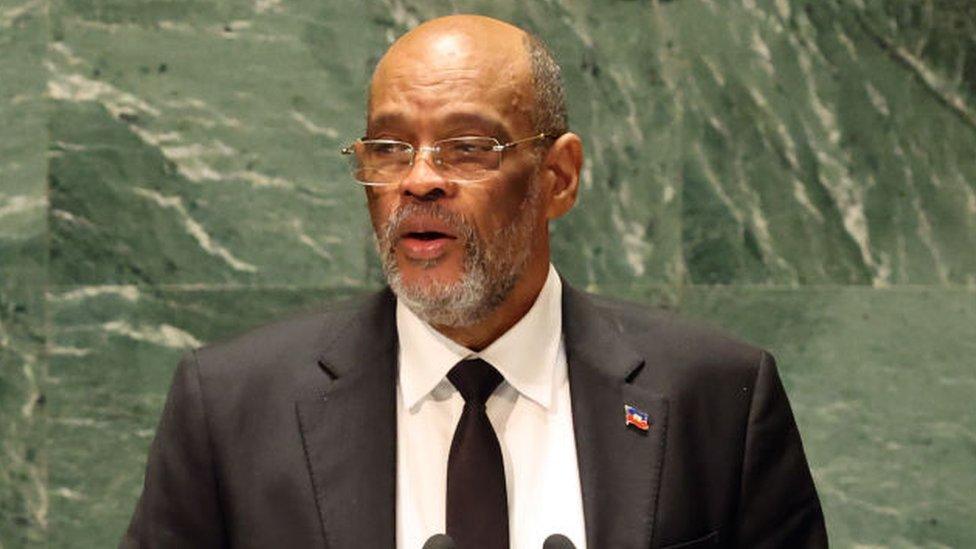

Since Jovenel Moïse's murder, the country has been governed by Ariel Henry.

Mr Henry had been designated by President Moïse as his prime minister shortly before he was killed. But some question his legitimacy to govern the country for years without fresh presidential elections being held.

Ariel Henry has been serving as prime minister since 2021 - the post of president has remained vacant

Opposition to Ariel Henry's leadership has been increasing as the elections he promised to hold have failed to materialise.

Moreover, insecurity has spiralled, forcing hundreds of thousands of Haitians to flee their homes.

One of the most outspoken rivals of Mr Henry is Jimmy Chérizier, a former police officer who became a gang leader after he was fired from the police force.

Also known by his nickname of Barbecue, the ex-cop leads G9, an alliance of nine gangs founded in 2020 which reportedly has links to late President Moïse's Tèt Kale Party.

Barbecue has opposed Prime Minister Henry from the start.

The gang leader used Moïse's assassination, which he blamed on the "stinking bourgeoisie", to encourage his followers to engage in what he called "legitimate violence".

Brutal attacks and looting spread, especially in the capital, Port-au-Prince, where Barbecue has his power base.

In October 2021, Ariel Henry was prevented from laying a wreath at a monument, when heavily armed members of Jimmy Chérizier's gang suddenly showed up and fired shots into the air.

Dressed in a pristine white suit and flanked by his men, the gang leader then proceeded to lay a wreath at the monument - an extraordinary show of force.

His G9 gang has also been fighting a bloody war with G-Pèp, a rival gang which is reportedly linked to the parties who opposed murdered President Moïse.

Shootouts and battles over territory between the two groups are common and have spilled over from the poorer neighbourhoods into the centre of Port-au-Prince.

Schools and hospitals have had to close and more than 100,000 people fled their homes in 2023, according to the International Organization for Migration.

The International Committee of the Red Cross told the BBC its staff had to talk to hundreds of gangs in order to be able to deliver humanitarian aid.

In a further flexing of its muscles, the G9 gang also blocked access to the Varreux fuel terminal in 2022, causing fuel shortages and hampering other key deliveries, such as medicines and drinking water.

Haiti's national police force - which according to 2023 figures only has 9,000 active-duty officers in the country of 11 million inhabitants - has struggled to confront the gangs, which are well armed with high-powered weapons smuggled in from the US.

Eighty percent of the capital is now estimated to be under gang control and the people living in these areas face "inhuman" levels of violence, according to the United Nations' humanitarian co-ordinator, Ulrika Richardson.

Ms Richardson said that there had been a 50% increase in sexual violence between 2022 and 2023 with women and young girls in particular targeted by the gangs.

Mr Henry has repeatedly called for international support to combat the violence, but so far only The Bahamas, Bangladesh, Barbados and Chad have formally told the UN that they plan to send security personnel.

But none have arrived so far.

During this latest spike in violence, Mr Henry went to Kenya to lobby officials there to make good on their promise to deploy 1,000 police officers to Haiti.

While Haitian civilians are desperate for more security, the deployment of foreign security personnel is viewed with concern by some.

Haiti, which became independent from France after the successful 1791 slave revolt, was occupied by the US from 1915 to 1934. Subsequent US military interventions between 1994 and 2004 have also made many wary of outside "meddling".

Some critics of Mr Henry fear he wants to use the Kenyan police force to prop up his power, just as protests calling for his resignation are mounting.

Jimmy "Barbecue" Chérizier is one of those who has accused Ariel Henry of trying to cement his power by inviting in foreign security personnel.

Jimmy "Barbecue" Chérizier is a gang leader who likes to style himself as a revolutionary

In 2022, the gang leader put forward his own plan for "peace", suggesting members of his gang be offered an amnesty and a "council of sages" be created with representatives from Haiti's 10 regions.

At the time he also suggested that his gang be given posts in the cabinet.

Since then, he has been ratcheting up the pressure, trying to present himself as a "revolutionary" who aims to overthrow what he says is an "illegitimate" leader.

On 1 March, Chérizier said he would "keep fighting Ariel Henry".

"The battle will last as long as it needs to," he added.

It is not currently clear where Mr Henry is, but with thousands of prisoners on the run and the powerful leader of the G9 openly calling for him to step down, the odds of the prime minister quickly re-stablishing order have just become more remote.

- Published4 March 2024

- Published8 February 2024