Seeking out the PKK gunmen in Iraq's remote mountains

- Published

PKK fighters use the mountains of northern Iraq as an attack base

In Iraq's northern mountains, Kurdish rebels the PKK plan and launch their attacks on Turkey. The BBC's Gabriel Gatehouse sought them out.

After a number of abortive approaches, we finally made contact with the PKK.

With the help of a guide, for hours we travelled by car along miles of bumpy, unpaved winding roads up into the Qandil Mountains of northern Iraq.

When we got to the camp, hidden in a dip in the mountains, our reception was friendly but guarded.

Few of the fighters wanted to talk to us. About a third of them are women. All were dressed in the same heavy green uniform. Most carried Kalashnikov rifles.

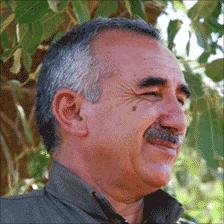

Under the shade of a tree, I sat down with their leader, Murat Karayilan. His cordial smiles and air of reasonableness soon turned to anger as he accused Turkish government forces of mutilating the dead bodies of his fighters.

"When one of our comrades is killed, Turkish soldiers cut his body to pieces and cut out his eyes," he said.

"We will go on. We will make whatever sacrifice is needed and we will not surrender, no matter what."

I challenged him to justify killing in the name of a political cause. He said he was willing to order the PKK to lay down its arms, under UN supervision, if the Turkish government agreed to a ceasefire.

Fighting for independence

The group's demands, he said, were an end to attacks on civilians and more rights for the millions of Kurds living in eastern Turkey, or northern Kurdistan as he called it.

But his offer was immediately tempered by a threat.

"We want the problem in the northern part of Kurdistan to be resolved through democracy.

"If the Turkish state does not accept this solution, then we will declare democratic confederalism independently."

Asked for a response to Mr Karayilan, a Turkish government official said it was "not in the habit of commenting on statements made by terrorists".

For more than a decade now, the PKK has used the inaccessible mountains of northern Iraq as a base from which to plan and execute attacks inside Turkey.

PKK leader Murat Karayilan says he is fighting for independence

They see this as a war of self defence, a fight for the survival of Kurdish identity.

The Turkish government regards the PKK as a terrorist organisation. Most governments, including EU states and the US, agree.

Only last month, there was a stark reminder of why. On 22 June a roadside bomb exploded next to a bus in Istanbul. The attack, which was claimed by a PKK splinter group, killed five people, four of them soldiers, one a 17-year-old girl.

The PKK launched its armed struggle against the Turkish government in 1984. Since then, the conflict has claimed the lives of more than 40,000 people on both sides.

A drive last year by Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan to solve the conflict with the Kurds through dialogue has stalled. Hundreds of Kurdish officials in eastern Turkey have since been arrested.

Earlier this spring, the PKK announced the end of its unilateral ceasefire. Since then more than 50 Turkish soldiers have been killed.

And this war is now being fought on two fronts: with Turkey to the north, and with Iran to the east.

Both countries have been hitting back, with artillery bombardment and air-strikes on Iraqi territory.

Scattering the villagers

At a village near the secret PKK camp, we saw some of the effects of this bombardment.

Two vast craters, filled with rubble and shrapnel, bore witness to a recent air-strike. Several houses had been badly damaged, their walls collapsed, glass shattered, the belongings of their inhabitants charred and scattered about.

Outside one of the houses, the twisted nose-cone of a shell lay in the dust.

The village was deserted, and there was no-one to ask about the circumstances of the attack.

But Kamal Chomani, a local journalist, said that villagers had told him that the destruction was the result of a Turkish air-strike which took place at the end of June.

The inhabitants of the village, he said, had moved into temporary accommodation in a school building nearby.

After years of massacres and oppression under Saddam Hussein, the Kurds of northern Iraq finally have their own autonomous homeland.

But, he said, the people here in these mountains have little choice but to show support for their fellow Kurds from other parts of the region who are still fighting.

"[The people of] this area, during Saddam Hussein's time, they were very revolutionary," he said.

"When any armed [PKK] forces come here, they have to listen to them, they are obliged to support them. Because, if they do not support them, they may have to leave their villages."

In other words, they are afraid.

And at the moment, many are paying dearly for that support.

In a deep valley at Doli Shahidan, not far from the Iranian border, there are hundreds of tents pitched in a dry riverbed.

Forgotten families

The setting is spectacular, with soaring craggy mountains on either side and small winding paths receding into the distance.

But for more than 500 families who have been forced to flee here over the past six weeks, the realities of life are less poetic.

Gabriel Gatehouse witnesses the effects of the attacks taking place inside Iraq

Mahmoud came here with his family in June, when Iranian shells fell on his village.

He is a farmer, dressed in a traditional baggy Kurdish tunic, held in at the waist with a length of cloth.

"Yes," he said, "there are PKK fighters in our area. But what can we do? They are armed. We just want to be left in peace to tend to our land."

It is the PKK and not Iraqi forces who control much of this mountainous region.

The government in Baghdad has protested to Tehran and Ankara over the shelling and incursions into its territory. But, say local people, not loudly enough.

Mahmoud and his fellow refugees are victims of a forgotten war, who have no idea when they'll be able to go back home again.

Correction 22 July 2010:

In the original version of this story we quoted Murat Karayilan as saying: "If the Turkish state does not accept this solution, then we will declare independence." We have clarified the translation of this sentence and corrected it to: "If the Turkish state does not accept this solution, then we will declare democratic confederalism independently."

- Published20 June 2010

- Published19 June 2010

- Published17 June 2010