Mid-East unrest: The discontent shaping new Arab world

- Published

It is only about two months since the first protests started in Tunisia. A desperate young man died after setting fire to himself because the police had stopped him selling fruit and vegetables.

Since then the presidents of Tunisia and Egypt have gone.

Demonstrators have learnt that if they push, if they overcome their fear of the police, then remarkable things can happen.

One of the leaders of the protests in Cairo told me that before their first demonstration on 25 January he thought they would last five minutes - that's a direct quote - before they were picked up by the police.

I don't mind admitting that the next day when I went over to Cairo I assumed that President Mubarak's state would be too strong for them.

But it wasn't and now it is clear that no Arab ruler can afford to feel safe. And the protests in Iran have started again as well.

The Iranian authorities, and the Arab ones in Yemen, Libya, Algeria and Bahrain are fighting back. Other leaders, and their secret policemen, wonder when it will start in their countries.

All have home-grown reasons for discontent. But they share some common characteristics.

One is government that is to a greater or lesser degree repressive.

Another is the frustration of young and growing populations, who know more about the outside world than any generation before them.

No taboos

Popular opinion in the Arab Middle East only really emerged 50 or so years ago, through radios in cafes and village squares that were often tuned to highly partisan broadcasts from Cairo.

Leaders concluded they could manipulate the way people thought.

Not any more. Pan-Arab satellite TV has been tearing away at taboos about what can be discussed since the mid 1990s. And now social media mean that everybody can join in.

Countries can't be shut off anymore. But their rulers have often continued to behave as if it was still 1960.

Many eyes are now on Bahrain.

For years, the Sunni royal family has been trying to tighten its hold over a population that is 70% Shia.

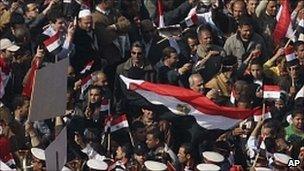

While the protests continue in Cairo, unrest is continuing to spread across the Middle East

It has brought in Sunnis from other countries to try to change the population balance. They've been given passports and other inducements that can include jobs with the security forces.

Bahrain is attached to Saudi Arabia's eastern province by a causeway.

Unrest among Bahraini Shias disturbs the Saudi royal family. The eastern province, which is where most of the oil is, has a large Shia population. It has been regarded as fifth column for the Shia rulers of Iran - though without much evidence.

Perhaps the Saudi royal family should feel nervous. The king and the crown prince are both old and ill.

Before the protests started in Arab countries Saudi Arabia was already worrying about the transfer of power to the next generation of princes.

And if the Saudis are worried, imagine the calculations that are being made in Washington, London and other Western capitals.

For years countries that pride themselves on democracy and human rights have backed undemocratic regimes that to varying degrees oppress their people. It has been a useful piece of diplomatic hypocrisy.

But now Western countries are going to have to deal with a new Middle East. And no-one at the moment has any idea how it will turn out.