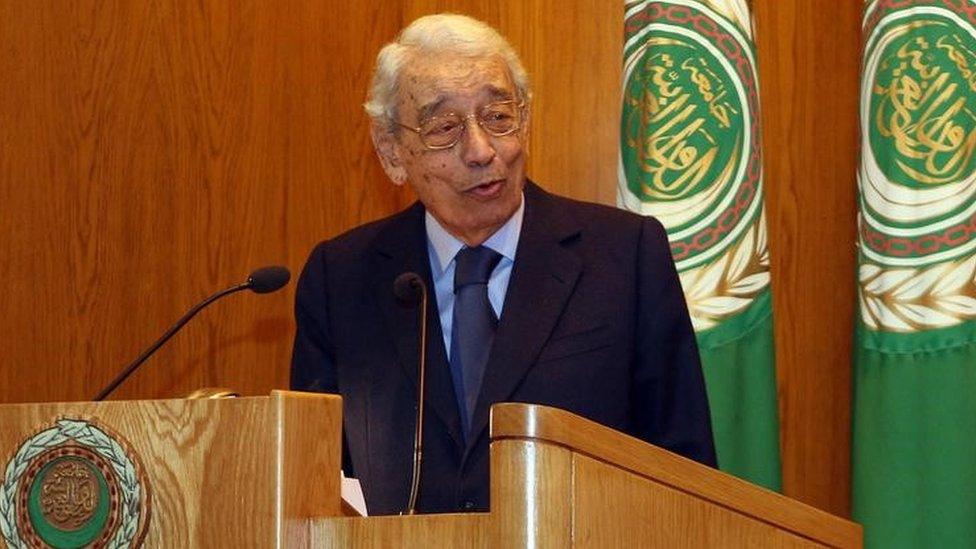

Obituary: Boutros Boutros-Ghali

- Published

As UN Secretary-General between 1992 and 1996, Boutros Boutros-Ghali sharply divided world opinion.

He was the first holder of the post to be denied a second term.

His five years in office were clouded by controversy, especially about perceived UN inaction over crises in Rwanda, Somalia and the former Yugoslavia.

To some, he was an effective diplomat with a formidable track record brought low by a widening rift between the UN and the United States. Others, most notably in Washington, saw him as a symbol of all that was wrong with the organisation.

Boutros Boutros-Ghali was born in Cairo in November 1922 into an influential Coptic Christian family. His father had served as finance minister in the Egyptian government, and his grandfather had been prime minister.

After taking a law degree at Cairo University, he completed his education at the Sorbonne and Columbia University in New York, before returning to Cairo as professor of international law and international relations.

He benefited from the then Egyptian president Anwar Sadat's policy of trying to heal the divisions between the dominant Muslim community and the minority Christians in Egypt, and served in Sadat's government from 1977, twice as acting foreign minister.

He was credited as the architect of the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty

He accompanied Sadat on his historic trip to Jerusalem in 1977, and was an architect of the Camp David accords which led to the Egypt-Israel peace treaty of 1979.

His influence survived Sadat's assassination in 1981 - he helped to fortify the American-led coalition against Iraq in the first Gulf War - and became Egypt's foreign minister under President Mubarak in 1991.

When Perez de Cuellar announced his retirement as UN Secretary-General later that year, Boutros-Ghali quickly emerged as a possible successor, even though he was already in his 70th year when the election was held.

And, in spite of his support for the Palestinian cause, Israel raised no objection to his appointment.

Slaughter

He had married into a prominent Egyptian Jewish family, and had a reputation for fairness and long-standing support for peaceful co-existence with the Jewish state.

Boutros-Ghali was one of 14 candidates for the post of Secretary-General, but won on the first ballot of the Security Council and took office as the sixth holder of the post on New Year's Day 1992.

His term coincided with a number of momentous international events. The Rwandan genocide, which UN peacekeepers on the scene were unable to prevent, led to the deaths of 800,000 people.

He was criticised for the failure of UN troops to stop genocide in Bosnia

The entire international community stood accused afterwards of looking on as the killers embarked on their slaughter.

The civil war in the former Yugoslavia seemed to drag on interminably. Once more UN troops, ostensibly there to keep the peace, were unable to prevent atrocities like the deaths on 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men in the Srebrenica massacre of July 1995.

And Somalia was hardly one of the more successful UN operations. The deaths of 18 US Army Rangers in Mogadishu in 1993 poisoned the waters between the Clinton administration and the UN.

This led to Washington becoming averse to using UN troops in peacekeeping roles, a turn of events which had disastrous effects, especially in Rwanda.

Daunting

But Boutros-Ghali's period in office saw countries look to a better future, too - South Africa being one example.

It held its first non-racial elections in 1994. The voting was both successful and memorable with long, patient queues of first-time black voters.

But HIV and Aids also tightened their grip on large parts of Africa and other parts of the world in the first half of the 1990s.

He became the first UN Secretary-General not to win a second term

Boutros Boutros-Ghali also faced the daunting task of securing more reliable funding for the UN and streamlining its bureaucracy.

Though he initially said that he would not seek a second five-year term, it was the United States veto which ended Boutros-Ghali's time at the UN in 1996.

The US, which owed the UN more than a $1bn dollars in unpaid subscriptions, saw Boutros-Ghali as an ineffective figurehead, who had failed to reform the financing of the UN.

Washington claimed that he was unable to define a mission for the organisation after the ending of the Cold War, and had presided over an unsuccessful peacekeeping strategy.

For his part, Boutros-Ghali saw the US as talking tough in the Security Council, but then failing to follow up its rhetoric with action on the ground.

He reserved particular scorn for the US State Department, writing later: "Coming from a developing country, I was trained extensively in international law and diplomacy and mistakenly assumed that the great powers, especially the United States, also trained their representatives in diplomacy and accepted the value of it.

"But the Roman Empire had no need of diplomacy. Neither does the United States."

After leaving the United Nations, Boutros Boutros-Ghali served as the first Secretary-General of La Francophonie, a group of French-speaking countries which includes Canada and former French colonies, as well as France itself.