Arab revolt: Could Oman turn into 'next Egypt'?

- Published

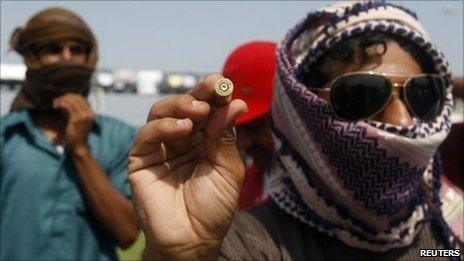

The level of violence in the port city of Sohar has shocked many Gulf experts

Observers are nervously watching Oman following unprecedented protests over the weekend, during which several people are reported to have been killed.

The big question is whether this previously stable Gulf state with a large and youthful population could turn into the next Egypt or Tunisia, and whether the unrest could spread to neighbouring giant Saudi Arabia.

One of the key differences between Oman and the larger Arab republics is that people are not (so far) calling for serious regime change.

Rather, they have demanded changes to things that directly affect them: job creation, greater state control over spiralling food prices, more power for the semi-elected majlis al-shura (lower house of parliament), and an end to the perceived corruption of some government members.

Protesters have also not gone as far as to directly criticise Oman's ruler Sultan Qaboos bin Said, who recently celebrated his 40th anniversary in power.

That Omanis would turn out to protest has not been a surprise for long-term Gulf watchers: the past few months have seen peaceful protests on two occasions. But the level of violence in Sohar, the centre of Oman's industrial sector, has shocked many.

Following the deaths in Sohar the US has urged Muscat to show "restraint", engage in dialogue and carry out reforms to widen participation in a "peaceful political process".

'One step behind'

Oman has long been a useful Arab ally to Washington, not least because of its steady relations with the increasingly isolated Iran. It was Oman's participation that helped secure the release of US hitchhiker Sarah Shourd from a Tehran prison last September.

So far, Sultan Qaboos has reacted in a typically Gulf manner, by dispensing largesse, creating new jobs and announcing an immediate government reshuffle.

Whether these moves will be enough to calm protesters - who have also staged sit-ins in Muscat in the past few days - remains to be seen.

Some observers have been scathing of the concessions, questioning how the already saturated public sector can cope with the 50,000 promised positions, and noting that it is the private sector that is meant to be driving job creation.

Analysts say that the cabinet is still - post reshuffle - staffed with those from within the system.

"Basically the reforms are too small and too late. They are one step behind the expectations of the people," said one academic who asked not to be named due to the sensitivity of the situation.

Sultan Qaboos remains genuinely popular in Oman

There are also key differences between Oman and neighbouring countries such as Bahrain, which has been hit by weeks of unrest. Oman has no organised and committed opposition, as there is in Manama, and there is no serious force within the political system calling for change.

It is also lacking the sectarian divide that has long caused problems for Bahrain and the national-expatriate balance is not as serious as in some of the other Gulf states. Civil society is still very weak and Sultan Qaboos is genuinely popular.

The Sandhurst-educated monarch is an old ally of the UK, and the Omani-British trade relationship is also important, with UK arms manufacturers having many successes over the decades. British Prime Minister David Cameron called into Muscat on his late February Gulf tour.

Saudi watch

Because Oman has long been one of the most stable Gulf states, analysts are keenly watching its neighbour Saudi Arabia for any signs of "contagion" - if unrest can hit the Sultanate, what will happen to the Saudi kingdom which suffers from more serious issues?

A Saudi "Day of Rage" has been called for 11 March. Just weeks ago, analysts would have said there was no chance of protests, but now there does seem to be the potential for violence.

In many ways, Saudi Arabia has by far the most serious problems of all the Gulf states - a large, youthful and sometimes restive population chafing under an ageing leadership.

There is unemployment and corruption, little political development and few personal freedoms. There has even been unrest in areas such as Najran and the oil-rich Eastern Province, where the minority Shia population is concentrated.

King Abdullah returned to Riyadh on 23 February from convalescence abroad. It will no doubt have comforted some of his people: he is a popular monarch, and the ruling Al Saud have proved resilient over the decades to other sweeping movements, from pan-Arabism to the Iranian revolution to Islamic terrorists.

But many Saudis are unhappy with the grants the king made on his return - an estimated $36bn (£22bn) spread across social programmes, job creation packages and higher salaries.

Adding to the mix is an increasingly infirm group of senior princes, with King Abdullah said to still be not entirely well following an operation in December.

A recent story put out by a dubious news outfit, that King Abdullah had died, saw the oil price leap before steadying.

And this is what many Western observers are worried about - that the least hint of unrest in the kingdom, the world's largest oil producer, could have serious knock on effects for the global economy.

Eleanor Gillespie is a Gulf specialist and a director of Cross-border Information, a London-based research company specialising in the Middle East and Africa.

- Published28 February 2011