Moroccans see limits of reform in rapper's case

- Published

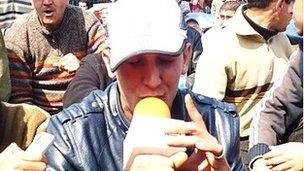

Mouad Belrhouate used his rap to criticise Morocco's rulers before he was arrested

For Morocco's protest movement, the case of rapper Mouad Belrhouate shows that the regime's authoritarian reflexes die hard.

The rapper, who goes by the name of El-Haked, or The Indignant, was arrested on 9 September, accused of physically attacking and injuring someone in a scuffle.

But according to Haked's supporters, the case was concocted because his lyrics dared to criticise the regime.

The 24-year-old remains in prison as Moroccans head to the polls to elect a parliament under a new constitution.

The authorities say the vote is an important step on the path of democratic reform, but for the beleaguered 20 February protest movement, Haked's case has become a rallying call as they appeal to people to boycott the vote.

'Silenced'

Moroccan activists say the plaintive in Haked's case, known as Mohamed D, is a well-known member of the royalist militias deployed over recent months to violently break up protests. They say he feigned injury to incriminate Haked.

"He was asking people to revolt and claim their rights, and he was fighting with all his energy against corruption in Morocco," says Abdelrahim Belrhouate, Mouad's older brother.

Stopping Being Silent by the rapper El-Haked, or The Indignant

"He was set up by the authorities… because of his songs," he says. "They put him in jail to silence him."

In one song, Stopping Being Silent, he addressed a taboo that has been breached but not entirely broken during the protests this year, directly challenging the monarchy and King Mohammed VI.

"While I'm still alive, his [the king's] son will not inherit," he raps.

Driss El Yazami, the head of Morocco's National Council for Human Rights, says Haked's case is being investigated, and that he is just one among "hundreds" of rappers.

The council is an official body created by the government amid a flurry of reforms prompted by the protest movement, and Mr El Yazami says Morocco is making big steps towards guaranteeing greater freedoms, noting that 65 of the 185 articles in a constitution approved in July refer to human rights.

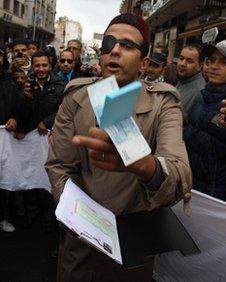

The protest movement has dwindled, but thousands turned out in Casablanca to call for a boycott

During an interview in the capital, Rabat, he reaches over for a pile of newspapers with front page articles about the king and the Western Sahara, topics traditionally outside the limits of critical discussion in Morocco.

"I don't agree that nothing has changed," he says.

"Of course, the fact that a right is in a constitution doesn't mean it will be applied automatically. The effective enactment of the rights in the constitution is a task that will last several years."

'Democracy now'

Moroccan authorities say the constitution paves the way for a constitutional monarchy in which the new parliament and a range of other bodies will provide democratic checks and balances.

But the protest movement is deeply sceptical, saying that without further change, the privileged elite aligned with the royal palace will retain power and wield it as they please.

Many say voting will make no difference, because the political parties are not strong or independent enough to represent them.

"On the first day we went out to call for a democratic constitution," says Hamza Mahfoud, a leading member of the protest movement in Casablanca.

Corruption is one of the grievances behind the demonstrations

"But the constitution is not democratic and will not lead to a constitutional monarchy. We are sticking to our demand of achieving democracy now, not later."

The protest movement has been criticised for lacking realistic and coherent goals, and it has dwindled since the beginning of the year.

The reforms may have taken some wind from its sails, and it has been subject to a smear campaign.

The movement's members have been painted as homosexuals - a common slur in socially conservative Morocco - and portrayed in parts of the media as a fringe bunch of contradictory secular revolutionaries and Islamist extremists.

But at a demonstration in Casablanca days before the vote, thousands turned out despite heavy rainfall to call for an election boycott.

"Nine months and we've not stopped," they shouted. "With the rain, with Ramadan, with the violence and the arrests - we're still there."

In the midst of the crowd two men dressed up as crooked politicians made jovial exchanges with the marchers.

One had the word "corruption" written over his bulging stomach, the other, hunchbacked, waved a fat cheque book in the air.

The slogans used also referred to social and economic complaints, to Morocco's mass poverty and sharp inequalities.

"The ministers are able to educate their children outside the country and we can't even educate ours here," goes one chant.

Cultural split

It is widely accepted that Islamists from the banned Justice and Charity movement have indeed gained power with the movement.

But they say there is nothing sinister about this. They say they have simply been forced outside the formal political process by a despotic regime, and see the more moderate Justice and Development Party (PJD) - which hopes to win the election - as too close the king.

Karim Tazi says Morocco risks a more acute social and economic crisis

The crowd at the recent Casablanca demonstration appeared to include a cross-section of society, though cultural gaps are clear.

While Hamza Mahfoud relaxed with a beer after leading chants during the march, a neatly dressed Justice and Charity youth wing member, Mohamed Balfoul, talked beforehand of persuading people through "education" that wine shops should be closed and women should wear the veil.

Both want democracy, though Mr Balfoul appears more outspoken, especially about the monarch.

"The king is outside the law. He is never challenged, we never question him," he says.

"That in itself seems bizarre - that he rules over 30 million people, billions of dollars of the country's wealth, and no-one can judge him."

Karim Tazi, the 50-year-old head of a furnishings business who has been outspoken in his criticism of the authorities and provided logistical support for the protest movement, says they are now wrong to be calling for a boycott.

But he also says the regime has much more to do before it achieves real reform, and that if it fails in this task, it risks provoking more widespread anger.

"The last hope I think is how the next government is going to behave within the framework of the new constitution," he says.

"I say the last hope because if it fails I'm afraid there is going to be a more acute social and political crisis with probably more spectacular consequences."

- Published24 November 2011

- Published17 November 2011

- Published28 October 2024