Tehran's Grand Bazaar re-opens after days of protests

- Published

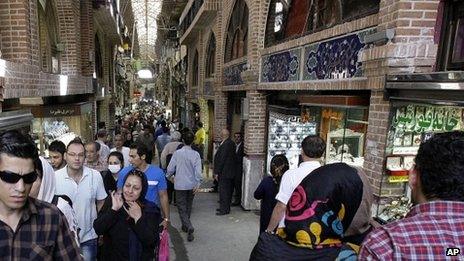

The historic Grand Bazaar is an important trading centre in Tehran

Tehran's Grand Bazaar - a maze-like complex of shops with its many narrow corridors selling more or less anything you can think of - was throbbing again on Saturday as it re-opened for business after being closed for three days.

The bazaar's traders brought down the shutters in protest at growing economic turmoil triggered by an unprecedented currency collapse.

Money changers triggered clashes with police on Wednesday that led to an angry demonstration against President Ahmadinejad's government, accusing it of mismanagement and wrong policies that led the national currency to plunge to record lows against the US dollar. Now, the rial seems to have stabilised and it was trading on Saturday at 28,500 to the dollar on the unofficial market.

As I walk along one of the bazaar's many corridors, the air infused with a mix of spices, especially cinnamon and cardamom, I stop to buy a cup of tea from a hawker carrying a big kettle.

"I earn almost 20,000 tomans ($15) a day, selling tea in the morning and lemon sherbet in the afternoon. But it is really difficult to make ends meet," Hojjat, 48, tells me. He has two daughters, one married. He has to work hard to provide a dowry for the other who is unmarried and working.

Shopkeepers fling open their shutters one after another, suspiciously looking around, as they say hello to neighbours and acquaintances passing by.

Today they have to host some uninvited guests - a heavy presence of uniformed police punctuates the network of corridors. Most carry no guns, handcuffs, or batons. They are just there. And, surprisingly, they start talking to the shopkeepers in a friendly manner. Soon it is as if they have known each other for years.

'Under pressure'

Mohammad Reza jokes with his friends about how "there are a lot of aliens" in the bazaar today, referring to the policemen. "We want to do business, but in the current economic climate it is impossible," he says.

"We import cloth and we have to pay in US dollars. With drastic fluctuations in the dollar rate, there is no room for manoeuvre. That is our problem. We need stability to make decisions."

Many people complain of feeling the pinch in the current situation

Beyn-ol-Haramein is one of the bazaar's most famous corridors and has a very beautiful mosque. In one of the shops there, Mehdi Esfandiyari has worked for more than half a century, since he was a boy of 12.

"We shut our shops for two reasons - both to show our protest to the government to stop wrongdoings in the economy, and for our own safety," he said.

"We are already under pressure; we do not want to lose our remaining assets in clashes between people no-one knows and the police. What if a lunatic sets fire to my shop?"

The bazaar traders are not alone in criticising the government because of what they believe is mismanagement by the president's administration. Almost all Friday prayer leaders bitterly criticised the government over its policies.

"The president talked irrelevantly about increasing living costs in his press conference that led to the bazaar merchants' reactions. He should not assume people just stupidly believe what is said," said Ayatollah Tabatabai, the Friday prayer leader in Isfahan.

'Serious message'

This is a serious message to President Ahmadinejad. Friday prayer leaders who used to be diehard supporters of the government are all appointed by Iran's Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei. Political activists believe they cannot criticise the president so harshly without the supreme leader giving the green light.

However, Mr Ahmadinejad continues to insist that all the trouble is caused by a tiny handful of foreign-inspired rioters and troublemakers who launched hefty psychological warfare against him in the last year of his term.

"If tolerating my presence in power is so difficult for you, I can write a sentence [of resignation] and say goodbye," he warned his opponents at his press conference a couple of days ago.

Many shops closed in sympathy with the demonstrators in the past week

Mr Ahmadinejad said the fall of the rial was caused in part by sanctions imposed by the West over Iran's disputed nuclear programme, which have prevented it from selling oil and transferring money.

He also blamed a band of "22 people in three separate circles" within the country, who with "one phone call" could manipulate foreign exchange trades in Iran.

While it is difficult to measure to what extent Iran's economic problems are down to the government's own policies and how far they are due to the effects of international sanctions, Iranian parliament speaker Ali Larijani believes the government has played a central role.

"The smaller part of the problem relates to sanctions while 80% of the problem is rooted in the government's mistaken policies. Robin Hood-like strategies do not work in Iran's economy," he said in an interview with the semi-official Fars news.

It is almost lunch time and in a restaurant in the heart of the bazaar, many people are tucking into Iran's famous chelo kebab. Almost everybody here is complaining that they are feeling the pinch of the hard economic times the whole country is going through.

Historically speaking, the bazaar will undoubtedly survive, but whether President Ahmadinejad finishes his second term in the normal way, or whether he writes a one-sentence letter of resignation remains to be seen.

- Published30 March 2015

- Published1 October 2012

- Published30 September 2012