Jeremy Bowen: Obama faces second-term Middle East challenges

- Published

Faced with a new generation of less compliant Arab leaders, America's political leverage in the Middle East is in decline

On 22 January 2009, 48 hours after he was sworn in for his first term as president, Barack Obama laid out his goals in the Middle East. Top of the list was to seek peace "actively and aggressively" between Israel and the Palestinians.

No-one, he said, should doubt America's commitment to Israel's security. But it would be "intolerable" for the Palestinians to face a future without hope.

In his remarks at the state department in Washington DC, President Obama - people were still getting used to putting those two words together - also paid a warm tribute to the leadership of President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt.

Four years later, the US is still committed to Israel's security. But there is no peace.

Palestinians have less hope for the future than they did four years ago. And former President Mubarak is serving a life sentence for his part in the killing of unarmed protesters during the revolution in Egypt almost two years ago.

The Middle East is in a process of change that will take a generation. It is driven by the wishes and needs of men and women under the age of 30.

However much the United States would like to influence, the people of the region show every sign of wanting to take back control of their lives from foreigners and their current and former allies in the region's palaces.

To his credit, President Obama shows every sign of realising America's limits. You get the feeling that President Obama would love to be able to turn his back on the Middle East.

A year ago he announced that US foreign policy would have a new priority. Not the Middle East, but Asia and the Pacific.

The trouble with that is the Middle East is too important to be left alone.

The United States has too many interests and commitments in one of the world's great strategic crossroads.

Green light for war?

In his victory speech, President Obama told Americans that 10 years of war were ending. But turbulence in the Middle East means that military action, perhaps even new wars, will be pushed back on to his agenda.

The Syrian war is leaking into neighbouring countries. No American president could afford to ignore so much trouble on Israel's northern border, in a part of the world that even before the Syrian fighting started was looking highly unstable.

In his second term, President Obama is likely to authorise more support for the Syrian rebels, short of direct US military intervention.

An even bigger decision awaits on Iran.

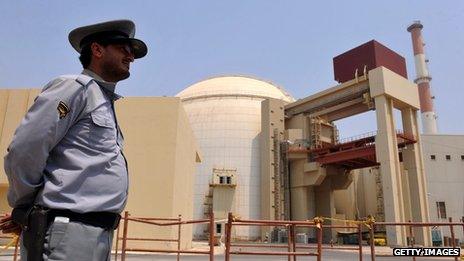

Iran insists it has a right to develop nuclear energy for peaceful purposes

If by next summer the US and its key allies still believe that Iran is developing a nuclear weapon, despite talks and sanctions, President Obama will have to decide whether or not to attack Iran's nuclear sites, or to give Israel a green light to go to war.

Iran has denied many times that it is developing a bomb, and its supreme leader has said that developing, possessing, stockpiling and using nuclear weapons is a grave sin.

Israel remains the only nuclear weapons state in the Middle East. But the policy of America and its allies towards Iran is defined by the belief that at the very least Iran wants the option of a nuclear weapon.

President Obama will not want to be part of another war in the Middle East.

His first move could be to improve the offer that has been made to Iran to give up its programme of enriching uranium to the point where it could potentially be made into a nuclear bomb.

Iran, faced with tightening sanctions, might be prepared to make a deal, which would end a highly dangerous, long drawn-out crisis.

Loss of leverage

But neither will Barack Obama want his presidency to be remembered as the time when Iran became a nuclear weapons power.

As a candidate in 2008 he told America's biggest Jewish lobby group that under no circumstances would he allow Iran to get a nuclear weapon.

The ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestinians is another thorny issue for Mr Obama

If Iran rebuffed an offer that President Obama considered fair, and if he felt Iran was going to go nuclear, there is every chance that he would order an attack.

The two-track policy, of accompanying negotiations with a military threat, has always had the threat of war as a endgame.

A peaceful settlement of the Iran crisis will not give the Obama White House much chance to draw breath in the Middle East.

More trouble between Israel and the Palestinians is overdue. When it comes, President Obama will be tempted to revive the push for peace he abandoned in his first term.

But it is probably too late for another realistic attempt at creating a Palestinian state alongside.

America has also to build new relations with Arab countries that have elected Islamist political leaders, and to respond if the Arab uprisings continue to spread to its allies in the Gulf.

Behind every decision that crosses the president's desk will be the knowledge that, despite its huge military power, America's political leverage in the Middle East is in decline.

Compliant, reliable, authoritarian allies have been deposed. And a new generation that sees America as an adversary, not a friend, is being empowered.

- Published7 November 2012