Guantanamo Bay: Why are so many inmates from Yemen?

- Published

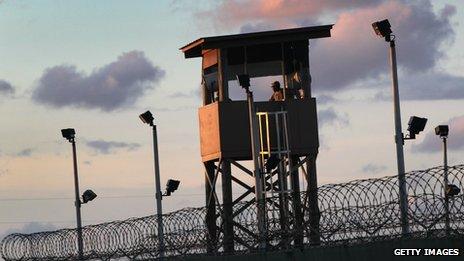

More than half of the detainees at Guantanamo come from Yemen

US President Barack Obama has lifted a moratorium on the transfer of Yemeni prisoners held at Guantanamo Bay as part of a renewed push to close the detention camp.

Nearly 800 detainees have passed through the centre since it was set up under the Bush administration in 2002 to hold "enemy combatants" from the war in Afghanistan - and 166 are still being held there, external.

More than half of these inmates - 89 men - come from Yemen.

They were largely picked up around in Afghanistan or border areas 11 years ago on suspicion of involvement with al-Qaeda.

But of the 86 men in Guantanamo who have been cleared for transfer or release, 56 are Yemeni. They are no longer considered enemy combatants or a threat to US security.

Many of other nationalities - including Europeans, Saudi Arabians and Afghans - have been moved on due to agreements with their home countries. But the Yemenis have been going nowhere.

'Too risky'

"The Europeans went home first, as did others whose home countries did quite a bit of advocacy on their behalf," said Martha Rayner, Clinical Associate Professor of Law at Fordham University in New York, who has represented some of Guantanamo's Yemeni inmates.

"The Yemenis had the misfortune of coming from a country that had had a dictator for many years - Ali Abdullah Saleh - and that didn't do enough to advocate for its nationals.

"So the Yemenis languished, even though many were approved for release by the Bush administration."

In January 2009, President Obama ordered the closure of Guantanamo within a year.

But on Christmas Day of that year, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab - a Nigerian trained in Yemen - attempted to set off a bomb hidden in his underwear on a Detroit-bound jet.

And the following January, President Obama issued a moratorium against the release of any Yemeni detainees. Combined with restrictions imposed by Congress, it brought releases and transfers to a virtual halt.

"I think it was a practical response," said Ms Rayner.

"It was a year since Obama had come into power and his critics were already galvanising themselves to challenge him on the issue of Guantanamo and connecting it to national security."

Matthew Waxman, professor at Columbia Law School and former Department of Defense adviser on detention issues, sees it as a more international issue.

"During that time, the view was that violent instability in Yemen made returning detainees too risky," he said.

"There was little confidence that the Yemeni government would be able to mitigate any continuing threat that the returned Guantanamo detainees would pose."

President Obama says Yemenis who have been cleared will be transferred "to the greatest extent possible"

Rehabilitation

Al-Qaeda gained territory during the Yemen revolution in 2011, taking control of towns predominantly in the Abyan region in the south west of the country.

Yemen's new President, Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, led a US-backed military offensive against them in the summer of 2012, pushing the insurgents out of Abyan.

But their presence continued - their numbers rose from hundreds estimated in 2009-2010 to several thousands believed to be operating in the country in 2013.

Suicide bombings and assassinations of military and security personnel became common. A growing anti-American sentiment has also been fuelled by a popular Shia Houthi rebellion and hated US military drone strikes.

This instability, combined with a lack of infrastructure and rehabilitation services in Yemen, means that Guantanamo's Yemeni detainees may not be going back just yet.

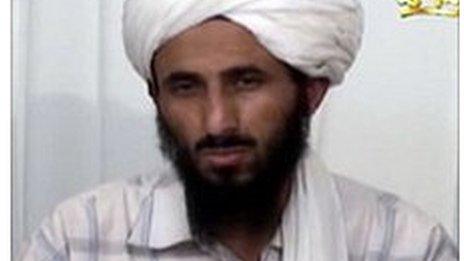

Former prisoner Said Ali al-Shihri, who was returned to Saudi Arabia, went on to become a leading member of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), now seen as the country's greatest threat.

US officials fear other former inmates - radicalised in the detention centre if not before - will go straight to fight for al-Qaeda once released.

Nevertheless, President Obama said on Thursday: "I am lifting the moratorium on detainee transfers to Yemen so we can review them on a case-by-case basis.

"To the greatest extent possible, we will transfer detainees who have been cleared to go to other countries."

President Obama vowed to close Guantanamo Bay in January 2009

Ms Rayner believes the move is connected to a hunger strike, which is being staged by around 100 detainees and has attracted worldwide attention.

"I think the hunger strike has made the Obama administration move Guantanamo up its priority list."

But Wells C Bennett, an expert in national security law at the Brookings Institution, said it was a sign of increased US confidence in the Yemeni government.

"It may mean that the administration is beginning to feel more positively about security," he said.

Analysts agree, however, that a number of hurdles remain, such as strict requirements imposed by Congress that mean that Guantanamo's Yemeni detainees may not be transferred or released imminently.

Much depends on how much energy the Obama administration is willing to expend.

"I am hopeful that a few Yemenis will go home," Ms Rayner said, "but I think it will be a small number."

- Published24 May 2013

- Published13 February 2024

- Published16 June 2015

- Published30 April 2013

- Published23 May 2013

- Published10 September 2012