Why there is more to Syria conflict than sectarianism

- Published

- comments

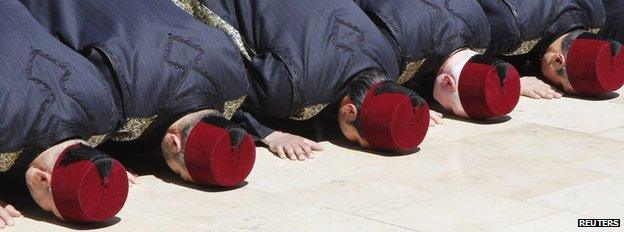

Sunni Muslims comprise about 75% of the Syrian population, with the remainder split between Christians, Alawites, Druze and Ismailis

"There is no nation of Arabs", the explorer and archaeologist Gertrude Bell, external wrote in 1907, "the Syrian country is inhabited by Arabic speaking races all eager to be at each other's throats."

The current conflict in that country is often branded sectarian too - yet despite the statements of some of the belligerent ideologists many Syrians refuse to accept the characterisation of it as a war based upon religion. So where does the truth lie?

Between the early 16th Century and 1918 the Ottoman Empire ruled much of the Middle East, including Syria. It tolerated non-Muslims, fostering cosmopolitan cities like Aleppo and Damascus, where many different creeds lived and traded in an interdependent manner.

Indeed the Ottoman system, which taxed non-Muslims at higher rates became financially dependent on this multi-cultural system carrying on.

While life between these different groups often carried on happily, the Ottoman system created intricate scheme of rules and restrictions, for example over where you lived or who carried out certain trades, which produced a highly developed sense of identity and group separation - inter-marriage was discouraged, not least by religious leaders.

Watch Mark Urban's film on Syria's long and complex history in full

In this elaborate pecking order members of Muslim sects regarded by the Sunni leaders as heretical, such as the Druze, external, Ismailis, external and Alawites, ranked below other 'people of the book', Jews and Christians.

Indeed Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, external, who travelled around Syria during 1810-12 found members of these Islamic sects operating underground, fearing death and pretending to be Sunnis, since they knew, "there is no instance whatever of pagans being tolerated".

Burckhardt saw that similar, violent, differences existed within the Christian community, notably between followers of Catholicism and Greek Orthodoxy.

He described the phenomenon as a, "system of intolerance, at which the Turkish governors smile, because they are constantly gainers by it".

The final decades of Ottoman rule were marked by growing instability and uncertainty, as some parts of the empire broke free to independence, and Western powers became increasingly involved, claiming to be the protectors of minority rights. In 1860 anti-Christian riots in Damascus left 8,000 dead.

When the British Army conquered Syria in 1918, the jostling for power between different groups became febrile. General Sir Edmund Allenby wrote from Damascus, "all nations and would-be nations and all shades of religions and politics are up against each other".

These tensions were managed to some extent by the French, who ran Syria between the World Wars, with a system of divide and rule. It had one important difference from that of the Ottomans. Sensing that the Sunni majority were in many ways their most violent and difficult constituency, the French kept them in check by advancing minorities in the army and other security forces.

By the time Syria's post-war nationalist civilian governments were overtaken by military rule in 1963, Christians, Druze and Alawites held many of the senior military jobs. By this time the secular, socialistic, pan-Arab ideology of the Baath Party had also become very important in the officer corps and it further empowered the minorities.

While anti-sectarian ideology became a central plank of the Baath Party, factions within it could not escape their sense of identity and tallying of who was lining up with whom. In 1966, for example, the loser of one army power struggle, a Druze, complained the Alawites were taking over, noting, "the sectarian spirit is spread in a shameful way in Syria, particularly in the army, in the appointment of officers and even recruits".

Hafez al-Assad, the father of the current Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, emerged victorious from these power struggles in 1970, and gradually managed to clamp down on his rivals, purging dissidents. Although he became the first Alawite president of Syria and put many members of his sect into key positions, Assad senior sought to portray his regime as non-sectarian: some of those he had defeated were also fellow Alawites, and some his supporters, such as the Tlass clan of his long-serving defence minister were Sunni, or from other non-Alawite minorities.

The Ottoman governor of Syria, Jamal Pasha, rides through Damascus in 1917

Even today, Bashar al-Assad's government generally avoids sectarian language, although the departure of key former supporters such as the Tlass family has left him ever more dependent on the Alawites and some other groups. The Damascus government's attempts to blame "foreign terrorists" and al-Qaeda for the country's difficulties harks back to its long term opposition to militant Sunni ideology.

In 1982 the regime crushed a rising by the Muslim Brotherhood in the city of Hama, leaving an estimated 20,000 dead. Although this was officially portrayed as a battle against a kind of extremism that endangered the country's multiculturalism, it was seen in many quarters as an attempt to thwart the Sunni majority from deciding Syria's future - and indeed this is how many members of that group view the current campaign of repression.

As the violence in Syria has intensified, outsiders have backed the different sides, and set the conflict into the context of a wider Sunni-Shia clash. Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah, leader of Lebanon's militant Shia Hezbollah movement, in seeking to justify his fighters' entry into the war has lambasted "takfiri" groups - a term for Sunni Jihadists who, like those Ottoman rulers of past centuries, regard Shias or Alawites as heretics fit for execution.

Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi, an influential Egyptian Sunni cleric, responded by calling two days ago for a Jihad against Hezbollah and Iranian interests in Syria. He says it is the duty of every Sunni to fight.

President Bashar al-Assad is a member of the Alawite community

Watching videos from the frontline of Qusair yesterday, it is interesting to see how this language of holy war - from outsiders it should be noted - has permeated to the Syrian foot soldiers. Sunni opposition fighters, taking a position manned by what they believe are Lebanese Shia fighters, refer several times to the "Party of Satan", a play on Hezbollah, which means Party of God.

Even at this dire hour, Syrian opposition people tell me about the Christians or Alawites in their movement, emphatically rejecting the label of Sunni Jihadists. Or government supporters will note the presence of non-Alawites in the higher reaches of the regime. Each meanwhile tries to tar their opponent with the sectarian label.

It is the long inheritance of Syria's history that leaves its traces of the Baathist or Ottoman belief that all peoples can get along in the greater national interest, and a certainty that for centuries people co-operated perfectly well.

But it is also this heritage that has left their society largely unintegrated, intensely aware of sectarian identity, and open - at least in part - to the messages of those who preach holy war.

- Published7 January