Egypt crisis: Who are the key players?

- Published

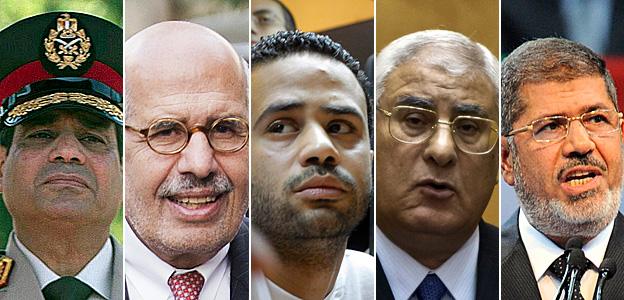

From left to right: Gen Abdul Fattah al-Sisi; Mohamed ElBaradei; Mahmoud Badr; Adly Mansour; Mohammed Morsi

The political crisis in Egypt has deepened following the overthrow of President Mohammed Morsi by the army.

His Muslim Brotherhood supporters say they will not accept his removal, while the military-appointed interim leader has laid out plans to change the constitution and for fresh elections.

Here is a guide to the key players shaping the course of events.

GENERAL ABDUL FATTAH AL-SISI AND THE MILITARY

The intervention by the military has underscored the position of the armed forces - led by defence minister General Abdul Fattah al-Sisi - as Egypt's most powerful institution.

Gen Abdul Fattah al-Sisi was instrumental in ousting Mohammed Morsi from power

Following days of mass protests against President Morsi, Gen al-Sisi warned that the military was prepared to step in "to stop Egypt from plunging into a dark tunnel of conflict and infighting".

The army issued an ultimatum to Mr Morsi, instructing him to respond to people's demands or step down within 48 hours. When he failed to do so, it removed him from power and placed him under house arrest.

On 3 July, Gen al-Sisi suspended Egypt's constitution and called for new elections. He was backed by liberal opposition forces and the main religious leaders.

The military's reputation was tarnished during the last transitional period, when it governed Egypt after the fall of then-President Hosni Mubarak. It was accused of breaching human rights and continuing authoritarian rule.

This time round it appointed an interim civilian leader and issued a roadmap leading to fresh elections and was viewed by anti-Morsi protesters as the saviour of democracy, rather than the perpetrators of a coup.

MOHAMED ELBARADEI AND THE NATIONAL SALVATION FRONT

The former United Nations nuclear agency chief, Mohamed ElBaradei, had been a favourite to lead a transitional government in Egypt after Mr Morsi was removed from office.

Mr ElBaradei, 71, is coordinator of the main alliance of liberal and left-wing parties and youth groups, known as the National Salvation Front.

Mohamed ElBaradei: "We were between a rock and a hard place"

It was formed late last year after Mr Morsi granted himself sweeping powers in a constitutional declaration.

Mr ElBaradei defended the army's intervention, saying Mr Morsi "undermined his own legitimacy by declaring himself a... pharaoh".

Presidential officials initially named Mr ElBaradei interim prime minister, but his appointment was rejected by Egypt's second biggest Islamist group, the Salafist Nour party, which said it would not work with him, and he was passed over.

He was then appointed interim vice-president with responsibility for foreign affairs.

TAMAROD (ANTI-MORSI MOVEMENT)

Tamarod, meaning "revolt" in Arabic, is a new grassroots group that called for the nationwide protests against Mr Morsi on 30 June, one year after he was sworn into office. It organised a petition that also called for fresh democratic elections.

The grassroots Tamarod movement had threatened open-ended protests if Mr Morsi did not resign

After millions of Egyptian took to the streets in Cairo and other cities, Tamarod gave the president an ultimatum to resign or face an open-ended campaign of civil disobedience. It was backed by the army.

Tamarod was formed in late April 2013 by members of the long-standing protest group Kefaya ("enough").

Kefaya successfully organised mass protests during the 2005 presidential election campaigns, but later lost momentum because of infighting and leadership changes.

Two representatives of Tamarod stood alongside Gen al-Sisi when he announced on television that Mr Morsi had been ousted.

One of them, Mahmoud Badr, urged protesters "to stay in the squares to protect what we have won". It has since issued statements supporting the military in its fight against what it calls "terrorism".

ADLY MANSOUR AND THE SUPREME CONSTITUTIONAL COURT

Adly Mahmud Mansour, the head of Egypt's Supreme Constitutional Court, was sworn in as interim leader on 4 July.

Mr Mansour praised the armed forces and the Egyptian people

As he took the oath, he praised the massive street demonstrations that led to Mr Morsi's removal. The revolution, he said, must go on so that "we stop producing tyrants".

Mr Mansour has set out plans to amend the suspended Islamist-drafted constitution, put it to a referendum and hold parliamentary elections by early 2014. They have been rejected by the Muslim Brotherhood and even criticised by the National Salvation Front and Tamarod.

Since the 2011 uprising, the Supreme Constitutional Court, Egypt's top judicial body, has made a series of rulings that have changed the course of the democratic transition.

Mr Morsi and his Muslim Brotherhood supporters claimed its judges remained loyal to the former autocratic leader Hosni Mubarak, who appointed them.

Last June, the court dissolved the Islamist-dominated parliament saying it was illegally elected. It also rejected a presidential decree by Mr Morsi to have it reinstated.

MOHAMMED MORSI AND THE MUSLIM BROTHERHOOD

Mohammed Morsi was Egypt's fifth president - and the first civilian and Islamist to fill the role. He had been in office for a year until he was ousted.

Critics have accused Mr Morsi of concentrating power in the hands of the Muslim Brotherhood

He is now reported to be under house arrest at an army barracks in eastern Cairo, where his supporters have been staging a sit-in.

Tensions increased dramatically on 8 July after the army shot dead some 50 supporters of Mr Morsi outside the barracks in disputed circumstances.

The Brotherhood said the attack was entirely unprovoked, and has called for "an uprising". The army said it was attacked by a group with live ammunition, petrol bombs and stones.

When he came to power, Mr Morsi promised to head a government "for all Egyptians" but his critics say he concentrated power in the hands of the Muslim Brotherhood, to which he belongs.

Opposition grew late last year, after he passed a constitutional declaration giving himself unlimited powers and pushed through an Islamist-tinged constitution. He has been repeatedly accused of mismanaging the economy.

Islamists have dominated the political scene since the 2011 Egyptian uprising, winning the majority in parliamentary and presidential votes. The Muslim Brotherhood has operated under its political wing, the Freedom and Justice Party.

The Brotherhood was founded in Egypt in 1928. Although it was officially banned for much of its history, its social work, charities and ideological outreach enabled it to build up a vast grassroots membership