Why al-Qaeda in Yemen scares the West

- Published

Whatever plot the US eavesdroppers overheard the top two al-Qaeda leaders discussing clearly rattled the US intelligence community so badly that Washington shut 19 of its diplomatic missions around the Middle East, Asia and Africa.

In the Yemeni capital, Sanaa, where the threat of attack is considered greatest, the UK, France and Germany have also shut their embassies.

The British embassy has emptied completely, with all remaining British staff leaving the country on Tuesday, while the US air force flew out American personnel.

So just what is it about al-Qaeda's branch in Yemen that triggers such warning bells in Washington?

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), al-Qaeda's branch in Yemen, is not the biggest offshoot of the late Osama Bin Laden's organisation, nor is it necessarily the most active - there are other, noisier jihadist cells sprawled across Syria and Iraq, engaged in almost daily conflict with fellow Muslims.

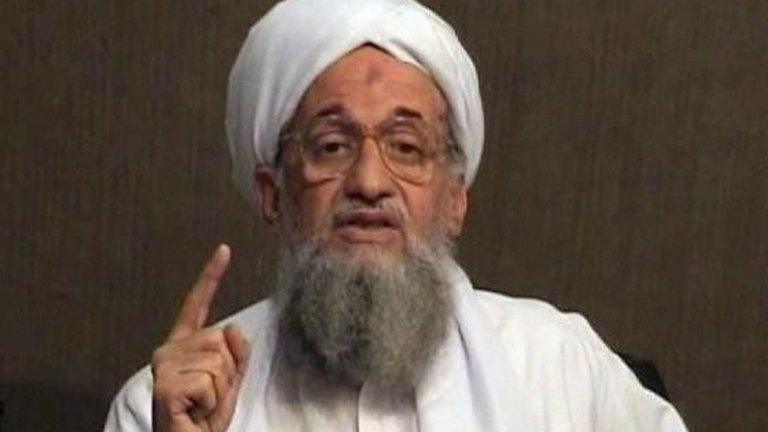

AQAP is loyal to nominal al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri

But Washington considers AQAP to be by far the most dangerous to the West because it has both technical skills and global reach.

Plus it is loyal to the nominal al-Qaeda leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and what remains of the group's core leadership hiding in Pakistan.

For the West, AQAP presents three dangers:

locally, to western embassies and citizens in Yemen

inspirationally, to potential jihadists around the world through its online magazine Inspire

globally, by putting bombs on planes

AQAP has form. In August 2009, its master bomb-maker Ibrahim al-Asiri, a Saudi national, built an explosive device so hard to detect it was either packed flat next to the wearer's groin or perhaps even concealed inside his body.

He then sent his brother Abdullah, a willing volunteer, as a human bomb to blow up the Saudi prince in charge of counter-terrorism. He very nearly succeeded.

Pretending he wanted to give himself up, Abdullah al-Asiri fooled Saudi security into letting him get right next to Prince Mohammed Bin Nayef before the device was detonated, possibly remotely by mobile phone.

The blast blew the bomber in half, but with most of the explosive force directed downwards, the prince had a miraculous escape with only a damaged hand. AQAP boasted that it would try again and it did.

In December 2009, Ibrahim al-Asiri devised another device to put on a volunteer, this time a young Nigerian called Omar Farouk Abdulmutallab.

He was able to fly all the way from Europe to Detroit with a viable explosive device hidden in his underpants, a massive failure of intelligence and security.

But when he tried to light it as the plane approached Detroit airport, he was spotted, overpowered, arrested and convicted of the attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction.

As Western intelligence heads scrambled to assess this new development, the British government decided to raise the UK national terror threat level to "critical", its highest ever. (It has since dropped back down to "substantial", the third highest of five.)

Drone attacks

The next year, 2010, AQAP tried again, smuggling bombs onto the cargo holds of planes hidden inside printer ink toner cartridges.

The intended destination was America and one device got as far as the UK's East Midlands airport. The plot was thwarted at the last minute by a tip-off from a Saudi informer inside AQAP, but the group has promised to keep trying.

Since then AQAP's leaders have come under continual attack from unmanned US Reaper drones or UAVs, losing several top operatives, including their deputy leader, Saeed al-Shihri, and the influential English-speaking propagandists Anwar al-Awlaki and Samir Khan.

According to the US think-tank the New America Foundation, US drone strikes in Yemen have soared, from 18 in 2011 to 53 in 2012.

A drone strike on Tuesday reportedly hit a car carrying four al-Qaeda operatives.

In Yemen, the US drones are deeply unpopular, sometimes hitting the wrong targets and wiping out whole extended families.

Human rights groups have branded them as a form of extra-judicial killing. Local tribes also view them as an insulting infringement of national sovereignty.

But US and Yemeni officials argue that in the wilder, more remote parts of the country, including Shabwa, Marib and Abyan provinces, targeting from the air based on tip-offs on the ground is their only means of stopping those plotting fresh attacks.

- Published6 August 2013

- Published6 August 2013

- Published16 June 2015

- Published5 August 2013

- Published3 August 2013