Egypt: Return to a generals' republic?

- Published

Many were delighted when the head of Egypt's armed forces, General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, ousted President Morsi in July

The last few weeks have seen violent scenes and several hundred deaths in Egypt following a crackdown on those protesting against the overthrow of democratically elected Islamist president, Mohammed Morsi, by the powerful Egyptian military.

That ousting was itself triggered by widespread protests against Mr Morsi's government, which had come to power following a period of military rule after Hosni Mubarak was forced out of office in 2011.

In this look back at the history and legacy of military rule in Egypt, Middle East expert Dr Omar Ashour argues that the challenges facing the country following the Arab Spring go back to the era of President Nasser and before.

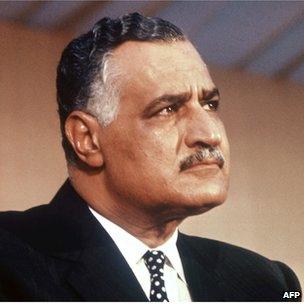

Gamal Abdul Nasser was involved in Egypt's 1952 military coup and later seized the presidency

"The coup leader - the hero Mohammed Naguib - gave an example of humility by refusing promotion to the rank of 'lieutenant-general'…This proves that the army does not want power, just the general good," wrote Egypt's renowned historian, Abd al-Rahman al-Rafai, in al-Akhbar newspaper on 1 August 1952.

His statement did not stand the test of time.

By February 1954, the humble general, who acted as Egypt's first president, was removed by younger, more power-hungry officers led by Colonel Gamal Abdul Nasser.

Egypt back then, as it is now, was divided.

One part of the country wanted a parliamentary democracy, a return to constitutionalism, and the army back to its barracks.

Another part of Egypt wanted a strong, unchecked charismatic patron who promised land and bread.

By November 1954, the latter part not only crushed the former, but also destroyed its demands. Basic freedoms and parliamentary constitutionalism were among the casualties.

Nasser did deliver on some of his promises, including land confiscation and redistribution, and confronting the United Kingdom, the former colonial power, in 1956.

But the cost was the establishment of an officers' republic: a state where the armed institutions are above any other, including the elected ones.

What do Egypt's generals want?

The January 2011 revolution challenged that 1954 status quo in many ways.

The revolutionaries did clash with a 21st Century junta: the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (Scaf).

The Scaf was a politically conservative, unconstitutional body that ruled Egypt between February 2011 and June 2012.

At the very least, security sector reform, democratic control of the armed forces, military and police oversight by civilian institutions, accountability to elected civilians, and budgetary transparency of the army were all radical, alien concepts for it. At worst, these concepts were threatening taboos and therefore should be eliminated or rendered meaningless.

After the removal of Mubarak in February 2011, the Scaf had a minimum of three demands it insisted on: a veto in high politics, independence for the army's budget and economic empire, and legal immunity from prosecution on charges stemming from corruption or repression.

It also wanted constitutional prerogatives to guarantee those arrangements.

These demands were reflected in a July 2012 constitutional addendum that gave the Scaf the prerogatives of the first post-revolution parliament, dissolved by Scaf's decision number 350 on 30 June 2012 (following a constitutional court verdict that part of the parliament's electoral law was unconstitutional).

This decision vested all legislative powers in the Scaf only days before Egypt's first elected civilian president was scheduled to take office in July 2012.

The independent military-economic empire, which benefits from preferential customs and exchange rates, tax exemption, land ownership and confiscation rights (without paying the treasury) and an army of almost-free labourers (conscripted soldiers), is a source of much military influence and thus another thorny issue for any elected civilian.

A black hole in the suffering Egyptian economy, post-revolution elected politicians might well seek to improve conditions by moving against the military's civilian assets and imposing oversight.

But in March 2012, a loud public warning was declared by General Mahmoud Nasr, a member of the Scaf in charge of financial affairs: "This is our sweat and we will fight for it….we will never allow anyone near the projects of the armed forces."

What do Egypt's generals fear?

Yet despite its power, the Scaf was quite sensitive to certain factors. Pressure from the United States is one of them, due to arming, training, equipping, and financing.

Street mobilisation is another factor. Most of the Scaf's pro-democracy decisions have come as a result of massive pressure from street protesters.

These include the removal of Hosni Mubarak, his trial, and that of other regime figures, and bringing the date of the presidential election forward to June 2012 from June 2013.

Coptic protesters were an easy target for the Scaf, argues Dr Omar Ashour

A third factor that influenced the Scaf's decision-making is the army's internal cohesion.

"The sight of officers in uniform protesting in Tahrir Square and speaking on Al Jazeera really worries the field marshal," a former officer told me.

One way to maintain internal cohesion is to create "demons" - a lesson learned from the "dirty wars" in Algeria in the 1990s and Argentina in the 1970s and 1980s.

Coptic protesters were an easy target to rally soldiers and officers against.

In October 2011, the army cracked down on a rally protesting against the burning of a church.

Twenty-eight Christian Copts were killed and more than 200 protesters were injured, but state-owned television featured a hospitalised Egyptian soldier screaming, external: "The Christians - sons of dogs - killed us!"

The systematic demonisation of anti-Scaf revolutionary groups, and the violent escalation that followed in November and December 2011, served the same purpose. After the coup of July 2013, the Muslim Brothers and Islamists became the new/old "demons".

The armed versus the elected

A forward step was taken towards balancing civilian-military relations following the election of President Mohammed Morsi in 2012.

In August of that year, Mr Morsi was not only able to freeze the constitutional addendum enforced by the Scaf in June 2012, but also to purge the generals who had issued it (Field Marshal Mohammed Hussein Tantawy and his deputy, General Sami Anan).

There was a price to pay for such moves, though.

President Morsi (at centre) may have been democratically elected, but civilian-military relations remained far from balanced, argues Dr Ashour

In the 2012 constitution, approved by 63.83% of Egyptian voters, civilian-military relations were far from balanced. Not only would the defence minister have to exclusively be a military officer (article 195), but also the National Defence Council (NDC) would have a majority of military commanders (article 197). This effectively gives the military a veto over any national security or sensitive foreign policy issue.

"If you add one of yours, I will add one of mine," yelled General Mamdouh Shahin, the army representative in the Constitutional Assembly, at Mohammed el-Beltagy, a now-wanted Muslim Brotherhood leader.

The latter suggested an additional civilian in the NDC, the head of the treasury committee in the parliament. His suggestion was rejected. And it was all caught on camera, external.

The July coup: From 2013 to 1954?

The July 2013 coup could lead Egypt into several bleak scenarios.

They are not certain, but the future of Egypt's democracy is certainly in danger.

When elected institutions are removed by military force, past patterns show that the outcome is almost never favourable to democracy: outright military dictatorship, military-domination of politics with a civilian facade, civil war, civil unrest or a mix of all of the above.

A few highlights include Spain in 1936, Iran in 1953, Chile in 1973, Turkey in 1980, Sudan in 1989, and Algeria in 1992.

The July coup is a backward step for democratic civilian-military relations.

Even more worrying are its regional implications.

The message sent by the coup to Libya, Syria, Yemen and beyond is that of militarising politics: only arms guarantee political rights, not the constitution, not democratic institutions and certainly not votes.

In the end, what remains certain is that no democratic transition is complete without targeting abuse, eradicating torture, ending exclusion, and annulling the impunity of security services, with effective and meaningful civilian control of both the armed forces and the security establishment.

This will always be the ultimate test of Egypt's democratic transition.

Dr Omar Ashour, external is a Senior Lecturer in Middle East Politics and Security Studies at the University of Exeter.

He is non-resident Fellow at the Brookings Doha Center and the author of The De-Radicalization of Jihadists: Transforming Armed Islamist Movements, external and From Good Cop to Bad Cop: The Challenge of Security Sector Reform in Egypt, external.