Syria crisis: Russia chemicals plan doable, says US

- Published

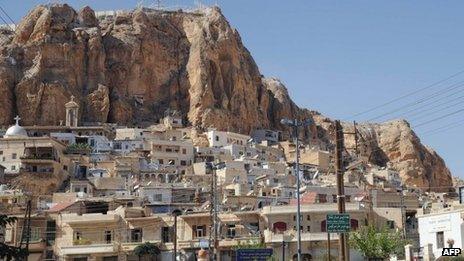

The BBC's Jeremy Bowen was in the town of Maaloula

Russia's plan to dismantle Syria's chemical arsenal is "doable but difficult", according to US officials.

The Russian and US foreign ministers are due to hold talks in Geneva over the plan, which involves Syria handing its stockpile to foreign observers.

Both sides are taking teams of experts, saying the disarmament process could be long and highly complex.

The US accuses the Syrian regime of killing hundreds in a poison-gas attack in the Damascus suburbs on 21 August.

The regime denies the allegations, but has agreed to abide by Russia's disarmament plan.

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has appeared on Russian television to confirm that Syria would concede control of its chemical weapons.

But he said it was because of a Russian initiative on the issue and not the threat of American military action.

Russia's foreign minister Sergei Lavrov has now outlined three main phases of the proposal:

Syria joins the Chemical Weapons Convention, which outlaws the production and use of the weapons

Syria reveals where its chemical weapons are stored and gives details of its programme

Experts decide on the specific measures to be taken

Mr Lavrov, completing a visit to Kazakhstan, said: "I am sure that there is a chance for peace in Syria. We cannot let it slip away."

He did not mention the destruction of the weapons, which is thought to be a sticking point in Moscow's negotiations with Damascus.

He is due to discuss the plan with US Secretary of State John Kerry, who will first hold talks with UN-Arab League Syria envoy Lakhdar Brahimi.

Officials travelling with Mr Kerry said they wanted a rapid agreement with the Russians on principles for the process, including a demand for Syria to give a quick, complete and public declaration of its stockpile.

The US postponed plans to launch military strikes on Syria after Russia proposed the disarmament earlier this week.

Russian media have hailed the move as a diplomatic coup.

President Vladimir Putin affirmed this view by writing an opinion piece, external in the New York Times lambasting US policy, saying strikes would lead to an upsurge in terrorism.

"The potential strike by the United States against Syria, despite strong opposition from many countries and major political and religious leaders, including the Pope, will result in more innocent victims and escalation, potentially spreading the conflict far beyond Syria's borders," he wrote.

BBC News asked people in the Middle East to share their views on a possible military strike against Syria

However, Western officials and the Syrian opposition remain sceptical over the willingness of President Assad's government to give up its arsenal.

State department officials have been stressing the exploratory nature of the talks with the Russians, saying they want "to see if there's reality here, or not".

UK Foreign Secretary William Hague said the Russian plan "must be treated with great caution".

And experts have pointed out the difficulty of conducting such a process in a war zone.

The rebels have already refused to co-operate.

Gen Salim Idriss of the Free Syrian Army said he categorically rejected the plan, and insisted that the most important thing was to punish the perpetrators of chemical attacks.

If the talks are successful, the US hopes the disarmament process will be agreed in a UN Security Council resolution.

However, Russia has already objected to a draft resolution that would be enforced by Chapter VII of the UN charter, which would in effect sanction the use of force if Syria failed in its obligations.

How the UN Security Council works

Russia regards as unacceptable any resolution backed by military force, or a resolution that blames the Syrian government for chemical attacks.

More than 100,000 people have died since the uprising against President Assad began in 2011.

Russia, supported by China, has blocked three draft resolutions condemning the Assad government.

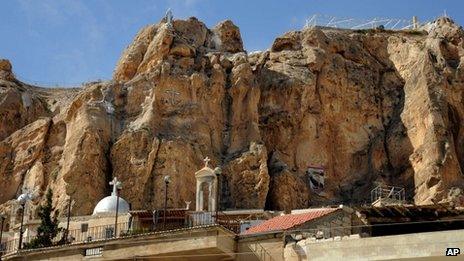

Maaloula is one of the earliest centres of Christianity in the world.

The town was overrun last week by rebel forces led by the al-Nusra Front, which is linked to al-Qaeda.

Government troops were forced to withdraw to the outskirts of the town. In one online video, smoke was seen rising from the St Sarkis monastery

After days of fighting, reports said the government had retaken the town. The BBC's Jeremy Bowen, who visited Maaloula, saw pro-government militia on the streets.

However, our correspondent said fighting was still going on around the town.

In normal times, Maaloula has been a magnet for tourists, drawn by its ancient monasteries and hermits' caves, and the fact that its people still speak Aramaic.

Now, there are fears for that heritage, with reports that militant Islamist rebels have attacked religious buildings and statues.

But opposition leaders have blamed pro-regime militias for that, accusing the government of terrorising minorities while trying to pose as their protectors.

On Tuesday, hundreds of Christians attended funerals in the capital's Damascus for three Maaloula residents killed in the fighting.

"Maaloula is the wound of Christ," mourners chanted as they marched through the narrow streets of the Old City's Christian quarter.