Jerusalem: Communities up close

- Published

Jerusalemites are preparing to cast their vote - or abstain in protest - in municipal elections. The city is home to the world's major religions and a host of social, political and economic issues. Here, the BBC's Erica Chernofsky looks at some of Jerusalem's diverse communities and the matters which concern them.

Oh, Jerusalem. The holy city, the city of gold, the city of peace. One of the oldest cities in the world, it has been conquered and reconquered, rebuilt and destroyed, for centuries.

Every stone has a story, every olive tree a history, and every mountain a different name, depending on who you ask.

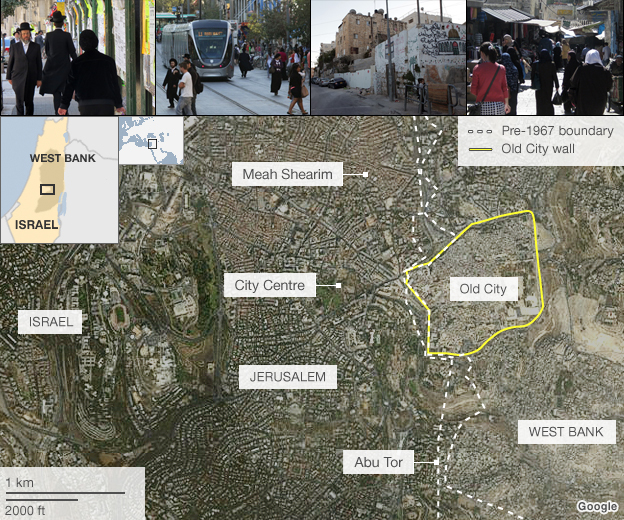

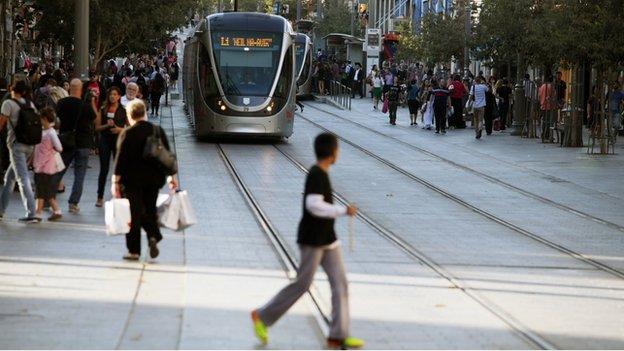

The city today is a vibrant mosaic of both ancient and modern. From the Old City walls overlooking dusty souks to the state-of-the-art light rail rushing past the upscale shops and five-star hotels of the Mamilla promenade, Jerusalem's ethnic landscape reflects the diversity of its population, a growing melting pot of Israeli society.

Despite its charm, Jerusalem is also a source of bitter disputes. It is a divided city, part Arab, part Jewish, and its ownership is still fought over, as ever.

Both Israel and the Palestinians claim it as the capital of their nations. Israel captured East Jerusalem in the 1967 war and later annexed it, but the international community does not recognise this sovereignty.

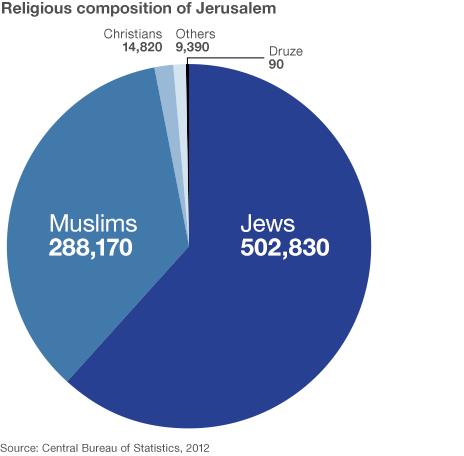

According to Israel's Central Bureau of Statistics, Jerusalem is Israel's largest city, but also one of the poorest, with higher unemployment rates than the national average.

There are a lot of issues that come with living in Jerusalem, and many of its residents feel the voices of their communities are not being heard.

Meah Shearim

Masada Porat grew up here, in Meah Shearim, an ultra-Orthodox neighbourhood in the western part of Jerusalem.

Rabbis are the revered leaders in ultra-Orthodox society, and it is not uncommon to hang photos of one’s rabbi in the home.

The ultra-Orthodox have a very strict dress code, and require women to dress modestly at all times, which usually means a loose shirt with long sleeves, a long skirt, and closed shoes.

City centre

Dor Sircovich lives here, in the centre of town, which holds an eclectic mix of religious and secular people.

Jerusalem’s secular residents are concerned that the ultra-Orthodox are encroaching on their neighbourhoods, and trying to impose their way of life on the city.

Traditional Jewish artifacts are sold in abundance in the tourist shops of the city centre. Here, a shopkeeper demonstrates a shofar, or ram's horn, traditionally blown on Jewish high holidays.

Abu Tor

Jewish and Arab residents live in the mixed Jerusalem neighbourhood of Abu Tor, where Khaled Saheb makes his home.

Palestinian children play with toy weapons near a mosque on the eastern side of the neighbourhood.

A group of girls on their way to a celebration for the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Adha.

Old City

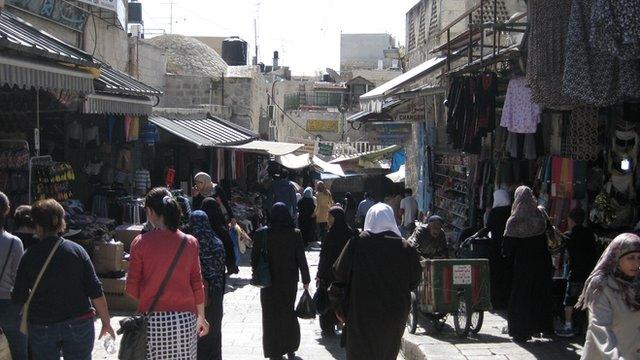

Damascus Gate of the Old City of Jerusalem is the entrance to the Muslim Quarter and the Arab shouk, where Khaled Saheb has his clothing shop.

The Old City of Jerusalem is surrounded by high stone walls and is made up of four quarters - Jewish, Muslim, Christian and Armenian.

The Old City draws locals and tourists, keen to experience its vibrant markets and famous religious sites.

MASADA PORAT, ULTRA-ORTHODOX CANDIDATE, MEAH SHEARIM

Masada Porat is the first ultra-Orthodox, or haredi, woman to run for the local city council.

Masada Porat: "They are against me because I am a woman"

The ultra-Orthodox community constitutes about a third of Jerusalem's Jewish population, and as such wields plenty of power over local life.

There was another haredi woman in the running, but she eventually backed out after reportedly receiving threats against her and her family from within her own community.

Ultra-Orthodox society is very closed and insulated against the outside world.

The men dress in traditional 19th Century religious garb and devote their lives to Torah study, while the women are required to dress very modestly and are mainly responsible for childrearing and supporting the household.

It is strongly frowned upon for a woman to draw attention by placing herself in the public spotlight, and the campaign has been a difficult one for Mrs Porat.

KHALED SAHEB, PALESTINIAN SHOPKEEPER, ABU TOR

There is another sector of Jerusalem society battling to have its voice heard, but most of its population won't even be voting.

Palestinian Khaled Saheb: "If I vote, it will give legitimacy to the occupation"

The vast majority of the Palestinians of East Jerusalem are not Israeli citizens and therefore cannot vote in national elections.

But they are officially residents of the city, and as such have the right to vote in local elections.

However, most of them will be boycotting the polls out of protest against the Israeli occupation and what they say is discrimination against their community by local government.

Khaled Saheb owns a small denim shop in the Old City souk just inside Damascus Gate.

He used to be a microbiologist, but took over his family's business after his father died.

He complains that living conditions are much worse on the eastern side of the city than on the western, mostly Jewish, side, and longs for a day when the Palestinians will be able to govern themselves in a state of their own.

DOR SIRCOVICH, SECULAR PUB OWNER, CITY CENTRE

Making Jerusalem more enjoyable for its residents has become almost like a mission for Dor Sircovich, owner of the popular local pub Bolinat and part of the city's decreasing secular population.

Secular pub-owner Dor Sircovich: "[Orthodox communities] are taking Jerusalem, neighbourhood by neighbourhood"

Many secular people complain that the city is becoming too religious, and resent the encroachment of ultra-Orthodox families on their neighbourhoods.

Large numbers of secular residents, including many friends of Mr Sircovich, have been leaving for more liberal places like Tel Aviv.

But he is determined to stay. His pub serves non-kosher food and is open on the Jewish Sabbath (Shabbat), therefore serving only the city's non-religious public.

Shabbat in Jerusalem means almost everything is closed down from Friday afternoon to Saturday evening.

Dor Sircovich wishes there was more entertainment spots like his, more places open on Shabbat, and less religious power over city life.

He hopes that the city's religious and non-religious population can find a way to live together in harmony, and to that end is even planning to open up a kosher restaurant, right next to his non-kosher pub, so that both groups can have common ground to connect and interact.

For now, the city remains divided, along a lot of different political, religious and ideological lines. It remains to be seen if a new local council can make any significant change in one of the most loved and contested cities in the world.

Video by Alon Farago; Photographs by Noam Sharon