Six things that went wrong for Iraq

- Published

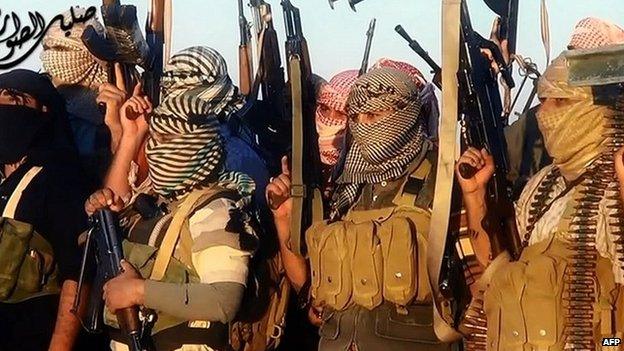

Fighters from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) have made gains in Syria and Iraq

The borders of the modern Middle East are in large part a legacy of World War One. They were established by the colonial powers after the defeat and dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire.

Those borders could now be in peril for two main reasons - the continuing fighting and fragmentation of Syria and the ISIS assault in Iraq Unless the military gains of ISIS can be reversed, the Iraqi state is in peril as never before. The dual crises in Syria and Iraq combine to offer the possibility of a "state" encompassing eastern Syria and western Iraq where the jihadists of ISIS hold sway.

This would have huge implications for the region and beyond. Iraq has to a large extent staggered from crisis to crisis, so what went wrong?

1. 'Original sin'

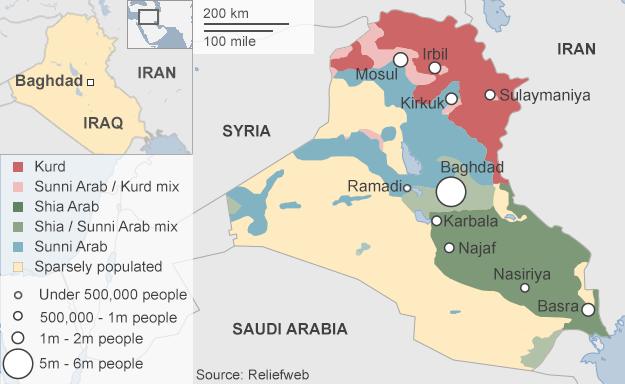

For some, Iraq's problems begin at the creation, with the founding of the modern Iraqi state itself. Britain, as the colonial power, established a Hashemite kingdom that took little account of other communities like the Shia or the Kurds - a theme that was to recur throughout Iraq's turbulent history.

The monarchy was eventually overturned by a military coup similar to the secular, nationalist and modernising forces that propelled the Nasser regime to power in Egypt.

It is this edifice that was eventually headed by Saddam Hussein whose Sunni-dominated regime dealt harshly with Shia and Kurdish sentiment.

Western support for Saddam during the Iran-Iraq War only seemed to consolidate his brutal regime.

2. Operation Iraqi Freedom

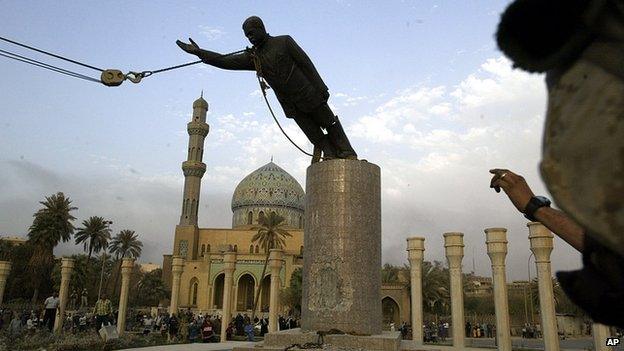

The toppling of Saddam Hussein left Iraq struggling to stay united

The Baathist state was destroyed by the US and British invasion of Iraq in 2003. Saddam Hussein was deposed and ultimately tried and executed by the new Iraqi government. Iraq's military was largely dismantled and a new security force created.

The war which some US neoconservatives saw as an explicit attempt to bring democracy to the region, established new political arrangements, which while seeking to unite all communities, effectively produced a state dominated by the Shia majority.

Many had actually wondered if Iraq could actually hold together as a unitary state, not least because the Kurds in the north had been able to carve out a significant degree of autonomy for themselves.

3. US pull-out

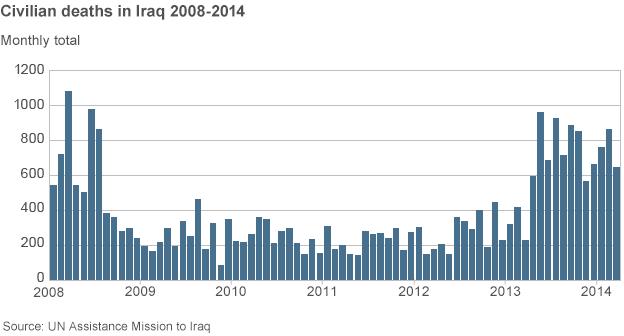

Despite initial plans to keep some forces in Iraq to assist the local army, no agreement could be reached between Baghdad and Washington, and the last US troops pulled out in December 2011 leaving security in the hands of the often less-than-effective Iraqi military.

The US had chalked up some significant successes in courting Sunni groups to help fight al-Qaeda-linked jihadist terrorism. Without the Americans these arrangements quickly broke down.

Sunnis found themselves increasingly the victims of the Shia-dominated government's security forces.

Indeed, the heavy-handedness of Iraqi forces may have effectively acted as a "recruiting sergeant" for ISIS.

4. Sectarianism in the new Iraq

The great paradox of the US overthrow of Saddam Hussein is that by destroying Iraq as a regional player they accelerated and facilitated the rise of Iran. Tehran saw the Shia in Iraq as its allies in a wider regional struggle.

Maybe emboldened by support from Iran, Prime Minister Nouri Maliki's Shia triumphalism antagonised many Sunnis worsening the security situation on the ground.

5. Economic and social failure

Sectarianism and the Sunni-Shia divide is seen by many commentators in a kind of chicken and egg situation.

Is it the sectarian differences in themselves that are the problem or is it that the Iraqi state's social and economic failure prompted more bitter divisions?

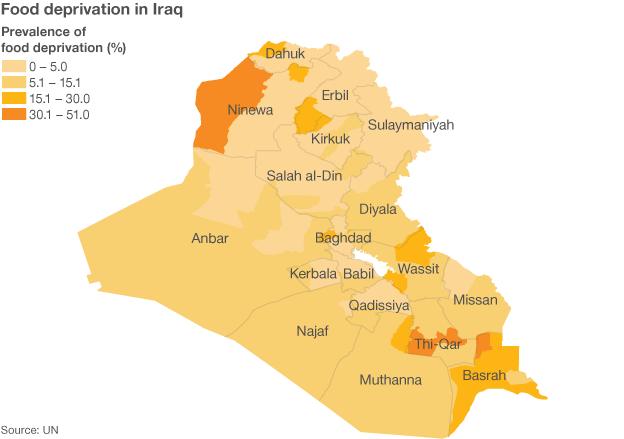

Iraqis - despite their country's oil wealth - are generally poor and levels of corruption in the country are very high.

6. Regional context

Nothing that happens in the Middle east occurs in a vacuum. Iraqis, while fixated inevitably on their own problems, have watched as the currents of the Arab Spring have come and gone; the almost circular political transformation in Egypt; and of course crucially the upheavals in neighbouring Syria. The jihadist surge there has inevitably had implications across the border in Iraq.

Backing for extreme Sunni fighters from the Gulf States has also facilitated the emergence and consolidation of groups like ISIS with a broader regional agenda.

And while direct collusion between Syria's Assad regime and the jihadists is hard to prove, there have been consistent reports that the Damascus government's military has paid far less attention to such groups while concentrating its fire on more moderate Western-backed fighters. This has given ISIS room to establish its own administrative structures in the areas it controls.