Factors behind the precipitate collapse of Iraq's army

- Published

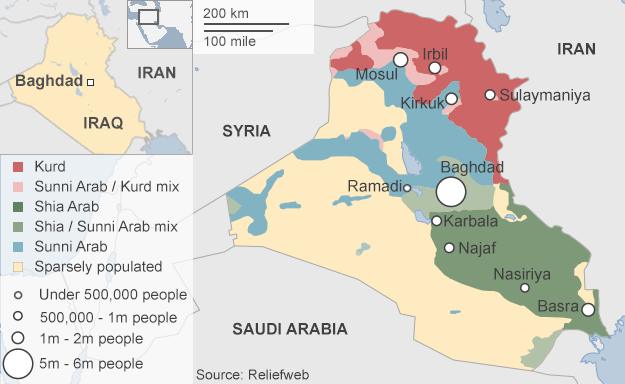

On paper Iraq's army should be able to overcome the numerically inferior IS

The collapse of the US-trained Iraqi military in the face of the initial onslaught from ISIS fighters and their allies underscores the perilous position confronting Iraq's rulers.

On paper, Iraq's military is a sizeable force - an army of over 193,000 to which can be added some 500,000 police and paramilitary forces of one kind or another.

It is a military that in many ways is still a work in progress. Iraq has very limited air power for example.

Nonetheless it is a force where - in the aftermath of the US military's departure in 2011 - some units at least might have been expected to acquit themselves well in combat.

Instead, they have largely abandoned their weaponry, stripped off their uniforms and fled.

ISIS may be a far more competent combat force than its description as an offshoot of al-Qaeda might suggest.

But it has been numerically far inferior to the numbers that the Iraqi government can put in the field against it. So why the precipitate collapse? This rests upon a whole variety of factors - such as military equipment, organisation and so on - but the fundamental reasons are probably political.

A "New Model Army"

In a step that was subsequently much-criticised, the US simply closed down Iraq's existing military after it evicted Saddam Hussein from power.

Iraqi security forces

193,400

soldiers

500,000+

police

-

-

$17bn military budget

-

$1.3bn US aid for Iraq

-

Iraq was 5th biggest recipient of US aid in 2012

In its place, it sought to establish a much more westernised army in terms of equipment and, crucially, doctrine and behaviour.

Creating any military from the ground up is a huge task. Some progress was indeed being made, but the project was always going to take many years.

The departure of US forces at the end of 2011 ended the close mentoring and training of Iraqi units.

It may also in hindsight have been a mistake to try to establish a Western-style military with high degrees of junior initiative, very different approaches to logistical support and so on.

Perhaps a hybrid approach should have been pursued, one that sought to mix elements of a modernised force with some of the traditions and culture more familiar to Iraqi troops.

Internal goals

In the first instance, Iraq's new military was designed and equipped largely for internal security duties.

Iraqi troops have been accused of abandoning their weaponry, stripping off their uniforms and fleeing

It was assumed that the defence of Iraq's borders - in case of a major threat from Iran for example - would be handled by the Americans.

So things like the development of an air force and the provision of an air defence network - things which in any case take considerable time to train for and equip - were not the main priority.

The challenge from ISIS has for now proved too much for the Iraqi force, and they lack things like air power to create the sort of rapid and decisive intervention on the battlefield needed to stem the advance of ISIS.

America's early departure

This had a fundamental impact on Iraq's capabilities, as well as on Washington's ability to get a full sense of what was happening on the ground.

US troops began pulling out from Iraq in 2009

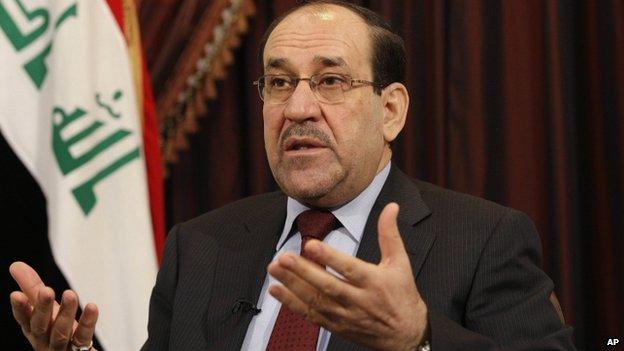

The Shia-dominated government of Prime Minister Nouri Maliki seemed intent on limiting any support for a meaningful strategic partnership with Washington.

Yes it wanted to buy arms from the US, but it also sought weaponry from Russia, Bulgaria and elsewhere.

Iraq's oil wealth gave it the funds to buy arms more widely and, to that extent, limited US leverage over Baghdad.

Iraq's sectarian contagion

Even before the departure of US troops, Prime Minister Maliki sought to put people loyal to him in key command positions.

Prime Minister Nouri Maliki has been reluctant to pursue a meaningful strategic partnership with Washington

With the Americans gone, this phenomenon accelerated. Command positions became increasingly prone to decisions taken on sectarian or family lines.

Corruption was rife - the very antithesis of the sort of professional military the US had hoped to create.

Increasingly, the military came to be seen as a sectarian force - one used by the Maliki government for its own ends.

As ISIS swept forward, a fear of the likely retaliation of the government forces, as much as fear of ISIS irregulars, drove thousands from their homes.

That tells you everything you need to know about the failure of Iraq's Shia-dominated government to establish a truly national army.

It is this last political dimension that is fundamental to the failure of Iraq's military.

It is also the failing that constrains any US action to bolster the Iraqi government's military position.

An intervention of US air power for example might stop ISIS in its tracks for now.

But without a fundamental change of heart from Mr Maliki or a willingness of Sunni and Shia factions to make the kind of compromises needed for effective national government, a unified Iraq may survive this storm, but many fear it will simply be living on borrowed time.

Analysis: How to recover Iraq's second city