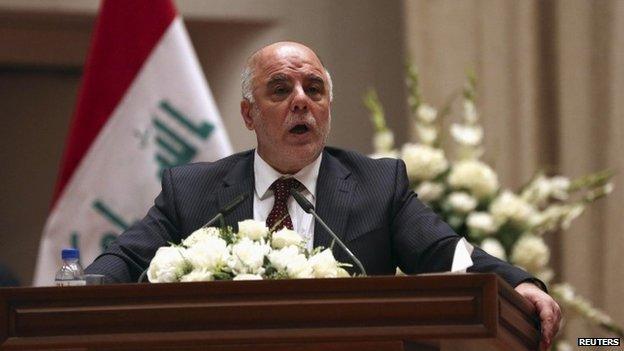

Haider al-Abadi: A new era for Iraq?

- Published

Haider al-Abadi hails from the same party as his predecessor, Nouri Maliki

Iraq's deputy speaker Haider al-Abadi is the country's new prime minister.

One of Iraq's most senior politicians, he has held several high-profile posts since returning to Iraq from exile in 2003.

He succeeded in deposing incumbent Nouri Maliki as the preferred candidate of the Shia State of Law parliamentary coalition, although Mr Maliki initially bitterly disputed the appointment.

But Mr Maliki later announced he would step aside and back Mr Abadi.

Mr Abadi faces the task of rebuilding trust between the Iraqi government and the country's Kurds and Sunnis, who felt increasingly alienated under Mr Maliki.

He takes over at a time of deep national crisis, as Islamic State militants have taken over large swathes of northern Iraq.

Suffered under Saddam

Born in 1952 in Baghdad, Mr Abadi studied electrical engineering at the University of Baghdad in 1975. In 1981, he completed a PhD at the University of Manchester in the UK.

He worked as an industry adviser and consultant in the UK during this time. For several years he was in charge of the company servicing the lifts at the BBC's Bush House, then the home of the World Service, and was known by several journalists there.

For much of the 80s and 90s, he was exiled from Iraq because he was a member of the Islamic Dawa party, an Iraqi Shia opposition organisation.

Haider al-Abadi has been at the top of Iraqi politics since returning from exile in 2003

Mr Abadi says two of his brothers were killed and another imprisoned for 10 years during Saddam Hussein's rule. They were all Islamic Dawa members.

After returning to Iraq in 2003, he became minister of communications in the Iraqi governing council, and has served as an MP since 2006. He has headed several Iraqi parliamentary committees, including those for finance and economics.

Moderate but firm

Mr Abadi has long been tipped as a potential prime minister and was in contention for the top job in both 2006 and 2010.

Analysts are generally agreed that he is a less divisive figure than Nouri Maliki. However, this tells us little as the bar for that comparison is so low.

The political background of both is rooted in the Islamic Dawa party, which in the 1970s waged an armed insurgency against the Baath regime.

Former foreign office diplomat Gerard Russell says that because of this, Mr Abadi is not too distant politically from his rival.

The president (2nd left) has asked Mr Abadi (right) to form a government

"He comes from a very similar background," he says. But he adds that, within the Dawa party, both men have taken differing approaches.

"Al-Abadi is a very clever man, and is a politician by background. Maliki had something more of an underground background," he says.

He will also be more attractive abroad, Mr Russell says.

"His name would probably not have been put forward without the approval of the Americans and the Iranians," he says.

"Of the three elected post-war prime ministers, he's certainly the most fluent in English and understands the West better," he adds.

Ranj Alaaldin, an Iraq specialist and visiting scholar at Columbia University, met Mr Abadi in April, during the Iraqi parliamentary elections.

He says that Mr Abadi is seen as a moderate within the Dawa party, and has shown more of a willingness to compromise than his predecessor.

"He is very engaging, articulate and direct," he says.

He warns however though that we should not expect radical changes from Mr Abadi, who still largely represents a specific subset of Iraqi society.

"He is still a politician with constituencies mainly in the south of Iraq among the Shias, and so his policies will reflect that," Mr Alaaldin says.

IS threat

When it comes to halting the advance of the self-declared "caliphate" of the Islamic State, Mr Abadi is unlikely to give an inch.

He told the Huffington Post, external in June that he would be prepared to "take any assistance, even from Iran" in the fight against IS militants.

"If US air strikes [happen], we don't need Iranian air strikes. If they don't, then we may need Iranian strikes," he said in the interview.

But he also admitted that there had been "excesses" by Iraqi security forces.

"We have to listen to the grievances, some of which are right and some of which are false."

Ranj Alaaldin says that during the militant insurgency in Anbar province, Mr Abadi believed that a strong military response was required in the short term but "stressed the importance of national dialogue and reconciliation in the longer term".

Mr Abadi faces the unenviable task of defeating a fearsome militant foe with a rattled army and vast areas of the country outside his control.

He will need all his powers of persuasion and influence to stand a chance.