Syria most dangerous place in the world for journalists

- Published

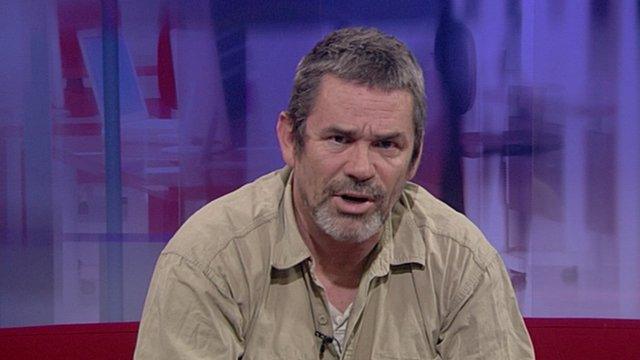

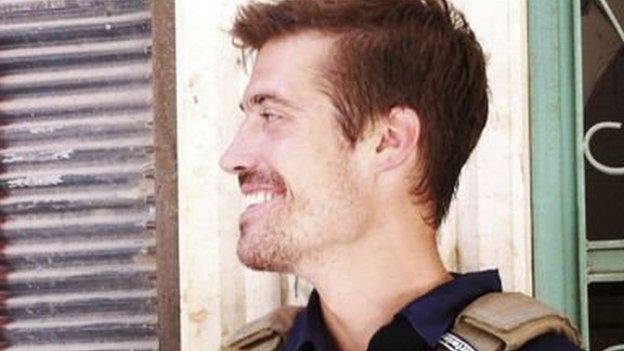

Top (l-r): Edouard Elias, freed after kidnap; Marie Colvin, killed in airstrike; Anthony Loyd, escaped kidnap. Bottom: Edith Bouvier, survived airstrike; James Foley, kidnapped and killed; Remi Ochlik, killed in airstrike

The murder of James Foley by Islamist militants after his kidnap in Syria in 2012 has focused attention on the dangers of reporting from the country.

It has been the most dangerous place in the world for journalists for more than two years, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), a New York-based press freedom lobby group.

At least 69 journalists have been killed as a direct result of covering the Syrian conflict since it began in 2011, the CPJ says; most were killed in crossfire or as a result of explosions, but at least six were confirmed to have been deliberately murdered.

The murders show that it is not just the widespread violence in Syria that is so dangerous for broadcasters and reporters; it is also the nature of the conflict itself, with its shifting alliances and ideologies.

Indeed, Syria is a very dramatic example of the way that war, and conflict journalism, have changed over the years in many parts of the world.

According to the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists, Syria is currently the most dangerous country for journalists. The BBC takes a look at the data.

Nature of the war

It is nowadays quite rare for wars to be between two armies, with a trench-like "frontline".

Journalists - and other civilians - increasingly find themselves in conflicts that involve ideologically driven insurgencies where there is no defined "war zone". In the case of radical Islamist insurgencies, the militants sometimes see journalists who are in any way associated with "the West" as part of the enemy.

"The barbaric murder of James Foley sickens all decent people", said Sandra Mims Rowe, Chair of the Committee to Protect Journalists.

The number of 69 confirmed deaths of journalists in Syria is almost certainly an underestimate because more than 80 have been abducted since 2011 and some 20 are still missing, according to the CPJ.

Some of them are feared dead, external, but accurate information is extremely hard to come by.

Sunday Times photographer Paul Conroy: "Without him, it will be darker"

Mr Foley's American nationality has clearly focused international attention on his case, not least because of the Islamic State (IS) statements about American military action.

But CPJ statistics show that the vast majority (88%) of writers and broadcasters who were killed in Syria in recent years were nationals of the immediate region.

An almost random look at the CPJ roll call of journalists killed in Syria reveals the case of Mohamed al-Khal, for example. He was a video journalist who documented clashes between government forces and the rebel Free Syrian Army in the eastern Syrian city of Deir al-Zour.

The New York-based Committee says he was killed by government shelling on 25 November 2012.

Ricardo Garcia Vilanova was kidnapped for six months in Syria in 2013

Mr al-Khal had contributed hundreds of hours of film, the CPJ said, to the Shaam News Network and some of the footage was used by broadcasters such as al-Jazeera and the BBC.

Freelance risks

Another victim was Yasser Faisal al-Jumaili, a freelance cameraman who was murdered in the Syrian city of Idlib on 4 December 2013. In his last known contact, via Facebook, the CPJ says, Mr al-Jumaili told a colleague he had been kidnapped by IS.

Nearly half of the journalists killed in Syria were freelancers - that is, journalists who work for more than one organisation and who are paid fees per piece delivered, rather than salaries.

Some were volunteers or activist "citizen journalists".

Spanish journalist Javier Espinosa is reunited with his son after six-month capture in Syria

Journalists who work for large international organisations have some advantages over freelance colleagues. They are often issued with body armour by their employers, for example, and some have "hostile environment" training, including for first aid.

Crucially, writers and broadcasters who earn salaries may be under less pressure to "deliver" from potentially dangerous situations and so might take fewer risks.

Indeed, in Syria, large established media organisations are increasingly relying on freelancers because they deem the country to be too dangerous for "their" people.

So far this year, 30 journalists have been killed worldwide, the CPJ says.

The most dangerous country is Syria with five deaths since the beginning of 2014. Four journalists have been killed so far this year in each of Ukraine, Iraq and Gaza.

- Published20 August 2014

- Published20 August 2014

- Published20 August 2014

- Published20 August 2014

- Published20 August 2014