Did inaction over Syria foment regional chaos?

- Published

Hundreds of people were thought to have died in the chemical weapons attack in August 2013

One year on from the deadly chemical weapons attack in Damascus that was widely blamed on the Syrian regime, the United States has used air power to try to change the regional balance of forces on the ground.

But the US air strikes have come in Iraq, rather than Syria. The US has been attacking fighters of Islamic State, an organisation that has only grown in strength due to the chaos in Syria.

One year on the Middle East is in a bigger mess than it was 12 months ago.

There is fighting in Libya; the torment of the Israeli-Palestinian struggle is in its latest phase of blood-letting; not to mention the linked tragedies in Syria and Iraq.

So much for the aborted hopes of what some called "the Arab Spring"; the brief flowering of the vision of a better, more democratic Middle East. The most important Arab actor, Egypt, which was in the vanguard of this process, has thrown reform into reverse.

Egyptian politics has turned full circle since the Arab spring

The controversial rule of the Muslim Brotherhood was overturned in what was for all intents and purposes a military coup. Egyptian politics has turned full circle, ending up pretty much where it began.

Inevitably this raises many questions. How far are the forces at work endemic in the region?

Could more be done - could anything be done - from outside to limit the chaos? And to what extent can coalitions of regional players - perhaps with support from outside - help to alleviate the multiple crises which have precipitated probably the worst regional chaos in living memory?

Assad stands firm

Of course a year ago, events in Syria were still seen to a large extent through the prism of the Arab Spring. If elsewhere, long-standing rulers and regimes had collapsed in the face of popular pressure, President Bashar al-Assad was determined to stand firm.

The divisions among Syria's opposition played to President Assad's strengths. The crisis was taking on more of a regional dimension with Sunni states, like Saudi Arabia, backing various elements of the opposition, while the Iranians strongly backed the Assad regime.

The West flirted with opposition groups but their disunity and the lack of Western resolve meant that there was no concerted effort to arm or equip them.

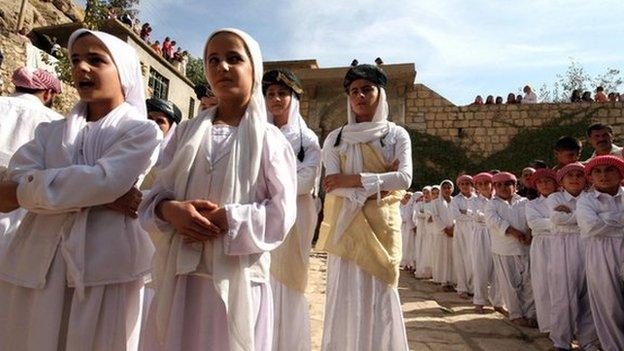

Removal of Syrian chemical weapons did little to alter the horror of the Syrian fighting

Then came President Assad's apparent use of chemical weapons against his own people.

There had of course been many earlier examples of such attacks. But the evidence of the chemical attack on the Damascus suburbs was clearer and sent out a clarion call for action.

On 31 August last year, in the White House Rose Garden President Barack Obama determined that the US should "take military action against Syrian regime targets."

The use of chemical weapons broke a long-standing international taboo. President Assad was deemed to have gone a step too far. But air strikes never came.

Obama's red line

Maybe President Obama was not wholeheartedly behind the idea of striking Syria, even though it had crossed his own self-declared "red line".

Perhaps on balance there was a better diplomatic outcome. But the vote of the British Parliament against joining any US air strikes greatly damaged the president's case as he sought congressional approval for military action.

Russia emerged with a diplomatic life-line of sorts; Washington and Moscow elaborated a plan, ultimately backed by the international community as a whole, which would ultimately see Syria's chemical weapons stocks removed and its chemical weapons production facilities destroyed.

It was a memorable chapter in the history of arms control, powerfully reinforcing the stigma of chemical weapons use. But in the tortuous story of contemporary Syria it was, to a large extent, a foot-note.

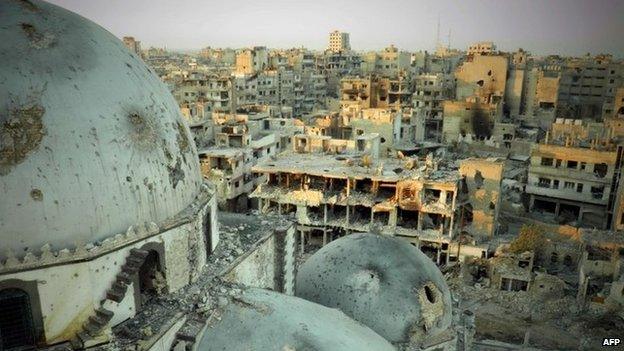

Three years of war has devastated Syria's main cities, and left nearly 200,000 dead

The bloody violence continued.

The regime retained its grip on a significant part of the country. And groups dubbed by the West as "the moderate opposition" have found themselves beset by an additional and deadly foe.

Jihadists benefit

Islamist extremists linked to an off-shoot of al-Qaeda had long been a source of concern in Western capitals.

Their ability to co-opt more moderate Islamists and to confront fighters backed by the West and its Gulf allies was one of the reasons cited for the reluctance to supply Western weaponry to opposition fighters.

Where might such weaponry end up?

But the removal of Syria's chemical weapons stockpile was in a sense a distraction.

It did little to alter the horror of the Syrian fighting. And President Obama's critics - some of whom argued for the use of air power not just in a punitive sense but to unseat the Syrian regime - believed that the White House had missed an opportunity to change the military balance in Syria once and for all.

In the absence of air strikes, they argue, it is the most extreme elements of the opposition - the jihadists - who have prospered. These groups have metamorphosed into the self-declared Islamic State that now controls a swathe of territory in both Syria and Iraq.

Islamic State militants are fighting government forces in Iraq and Syria, making significant advances on the ground

So this is where we are today.

The difference being that in Iraq the US has used its air power, albeit to a limited extent, while it refrained from doing so in Syria. So why the difference? For some the easy answer is oil.

True, Iraq - for many reasons - is seen as being of greater strategic importance. But then of course the US has a residual responsibility in Iraq on the principle that "if you break it you own it".

The US is a long-standing ally of the Kurds and Washington received an explicit request for assistance from the government in Baghdad.

The view in Washington is that there is a crumbling constitutional order in Iraq to prop up.

Syria is an altogether different situation.

It is hard to say what would have happened there if Mr Obama had followed through on his threat of air strikes a year ago.

But what is clear is that the failure to contain Syria's disintegration now threatens the integrity of Iraq too.

An extremist Islamist statelet has been formed across the territory of the two countries; an entity that could one day export its violence even further afield.

- Published7 August 2014

- Published21 July 2014