Will Obama's global anti-IS coalition work?

- Published

Islamic State and al-Qaeda are the world's most dangerous jihadist groups, analysts say

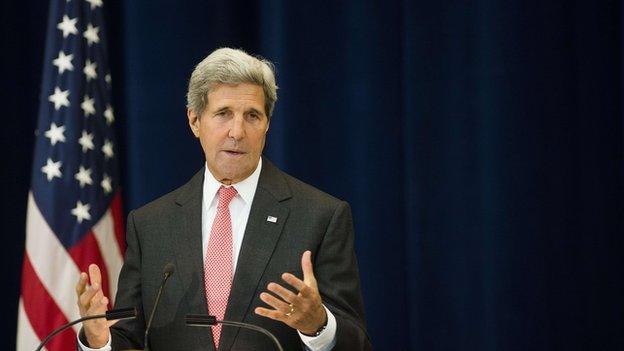

US Secretary of State John Kerry has completed a tour of the Middle East, trying to enlist allies in the fight against Islamic State (IS).

During his campaign to recruit allies, he has managed to win the support of 10 Arab countries including Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

As the international community ratchets up the response to the group, the BBC's Jonathan Marcus examines how this coalition is being set up and the chances it will meet its goals.

Why is the US taking such a strong line with IS?

The scale and scope of Islamic State (IS) marks it out from other jihadist groupings insofar as it already controls a significant swathe of territory across Syria and Iraq.

IS has captured huge quantities of weaponry and has significant financial resources, giving it more of the character of a quasi-state rather than a cell-like terrorist organisation.

With its ambition to establish an Islamic caliphate expanding from the areas it already controls, it represents a clear threat to US allies in the region and, given the significant numbers of foreign fighters in its ranks, potentially to Western countries as well.

What support has John Kerry managed to secure?

US Secretary of State John Kerry has received strong backing - at least on paper - from pro-Western states in the region.

A declaration signed earlier this week noted a range of measures that will be required - not just military action: controlling borders, clamping down on the funding of IS, efforts to counter its ideology and to constrain foreign fighters from joining it.

John Kerry has been trying to persuade Western and regional allies to contribute to the military effort against IS

A number of Washington's Western allies are also stepping up to the mark, with Australia announcing that it will send 600 personnel, initially to the United Arab Emirates. (This is believed to include Special Forces soldiers to help train Iraqi and Kurdish units along with six FA-18 Super Hornet fighters, tankers and other support aircraft.)

France, too, looks likely to become involved militarily.

The matter was discussed at the recent Nato summit in Wales and more countries are likely to announce their contributions as the nature of the mission becomes clearer.

A senor former US general, John Allen, has been appointed to co-ordinate what looks set to become a large and diverse coalition that may have to remain in existence for some considerable time.

Can regional countries not do this on their own?

The Mehdi Army led by influential Shia cleric Moqtada al-Sadr fought against US troops during the occupation

They simply do not have the skills or capabilities required. Even some units from the US-trained and equipped Iraqi army collapsed under IS attack - although this force had been hollowed out to a considerable extent by the corruption and favouritism of the regime of former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri Maliki.

The US and its allies will not do the fighting on the ground. But they will provide the key enablers - air power and the means to ensure that the application of that air power is effective.

President Obama has framed the use of Western air power very much in terms of helping Iraqi forces on the ground.

In Syria, where the situation is even more complex and where there may not be a credible Arab-backed pro-Western ground force, US bombing may have to remain intelligence-led, attempting to degrade the IS leadership and facilities.

Is Britain likely to join the US in strikes against IS?

All the signs from London are that Britain will join in although it is unclear when an announcement on military action might come and whether it would encompass just Iraq or extend to Syria, too.

Britain was quick to assist Washington in supporting Kurdish fighters and to help rescue the stricken Yazidi community.

The UK sent four Tornado jets to Cyprus to carry out reconnaissance flights (they are still there and could be used in an offensive capacity); it also sent a Rivet Joint intelligence gathering aircraft and it was ready to employ Chinook helicopters and some supporting ground troops to rescue stranded civilians.

UK Prime Minister David Cameron also has some domestic political factors to contend with.

Does the parliament vote last year against bombing in Syria (at the time of the chemical weapons crisis) preclude UK action in Syria now?

The UK foreign secretary certainly indicated that it did last week before being criticised by Downing Street.

The horror of the murder of a British aid worker clearly compels Mr Cameron to act resolutely - this is the direction that he was already travelling in, but the referendum on Scottish independence may mean a brief delay in any announcement.

The contest there is so close that any decision in London on military action might tip a vital fringe of Scottish voters into the "Yes" camp given the wider hostility to what some might see as "London's wars".

The US has a powerful military, why does it even need allies?

The US has formidable air power but needs allies to send ground troops

For political and practical reasons. The US has something of a bitter legacy in the region given the failures in the aftermath of the campaign to topple Saddam Hussein.

This has not been improved by what many of Washington's Arab allies see as Mr Obama's vacillation and unwillingness to act decisively.

Building a broadly-based coalition is thus important both for the Middle East itself - to convince people that this is not an Iraq War mark II - and for US public opinion at home, to persuade them that there will be no drift into a major commitment of boots on the ground - that it will be America's local allies who do the fighting.

Large numbers of US troops struggled to "win" in Iraq and Afghanistan. There is no chance of major commitments of US ground forces, so that part of the war will depend upon local allies.

How long might it take to destroy IS?

There are two questions here - is it actually possible to "destroy" rather than to degrade and contain IS? Many US analysts have questioned Mr Obama's goal of destroying the movement since they say this cannot be done.

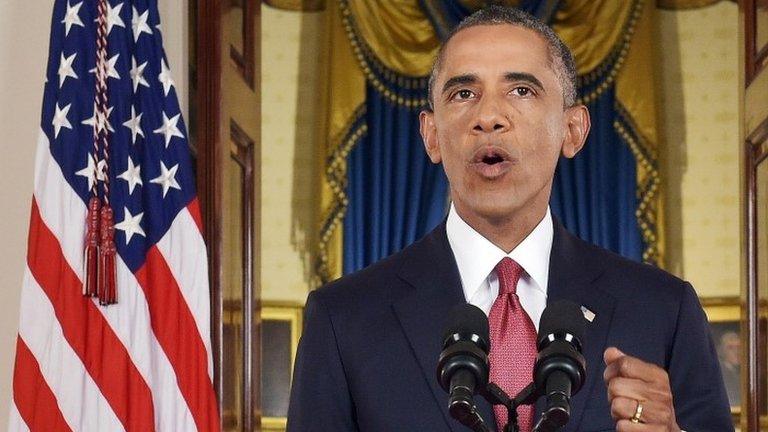

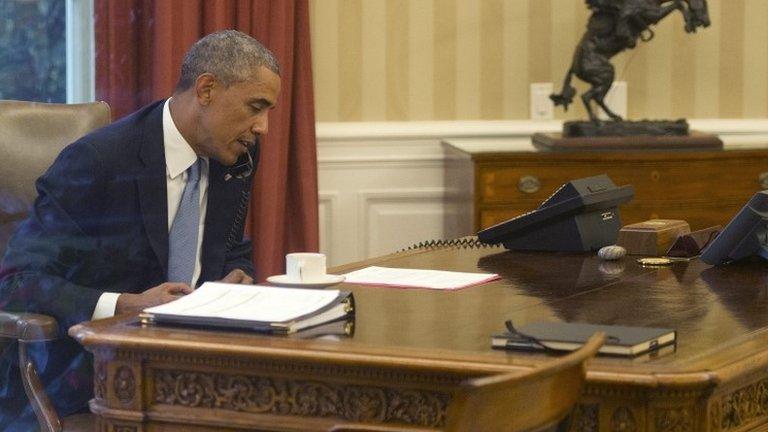

President Obama: "We will degrade and ultimately destroy" IS

Such groups tend to disappear - look at the rise of al-Qaeda in Iraq during the US occupation, which was largely defeated when he US co-opted local Sunni groups. IS is to an extent a return of this phenomenon in another form.

Either way the struggle against IS is going to be long-term, not least because the vital ground elements of the coalition campaign such as Iraqi forces need to be trained and integrated with Western air power.

The campaign in Iraq is one thing - at least it has a government of sorts (although this is only now beginning to become more inclusive and has a very long way to go in providing even the most basic standards of governance) - but in Syria it is another set of problems again.

It is instructive that US spokesmen have begun to talk about the struggle against IS in terms of it being a "war". So dig in for the long haul.

Can this war be successful without Iran and Syria on board?

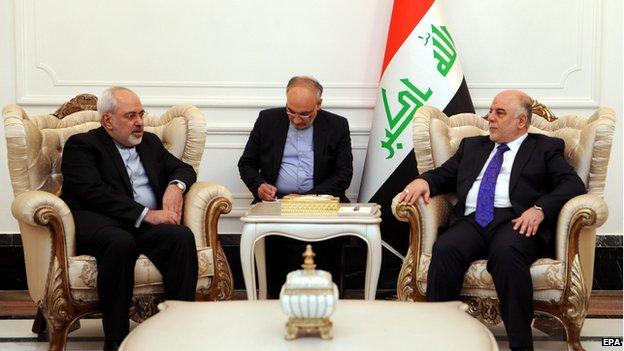

Iraq's new Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi (R) has close ties with Iran's Foreign Minister Javad Zarif (L)

Iran is a vital factor and its support for the Baghdad government is a key element in helping it to withstand the IS assault.

But the US is insisting that here can be no explicit relationship with Iran, though talks between US and Iranian officials have been held in the margins of other meetings.

The problem is that while the US, Gulf Arab and Iranian interests align to an extent over Iraq, they are at loggerheads in Syria. Iran is one of the few countries to still back the Assad regime there.

US and coalition policy towards Syria is complicated by the fact that while the Syrian government is fighting IS, the coalition will not want to have any explicit links with Damascus. This is a case of my enemy's enemy is not my friend.

It is the chaos in Syria that has helped IS establish itself and then export its brand of barbarism back into Iraq.

So without a long-term solution to the Syria crisis, its territory may remain a refuge for IS, making the group's destruction that much harder.

How does this coalition differ from previous ones?

Western countries are keen to avoid a repeat of previous campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan

All coalitions tend to be similar to an extent, and at the same time, different from those seen during other crises.

In 1991 a coalition of some 30 countries was assembled by the Americans to evict Iraqi forces from Kuwait.

It included key Western military players like France and the UK, but also key Arab states like Saudi Arabia, Egypt - and Syria as well.

The difference was that it was a brief military campaign, with a clear and attainable goal.

Ever since 9/11, the wider struggle against al-Qaeda has also drawn upon a broad coalition of countries.

Large numbers of countries have contributed troops to operations and peace-keeping duties in Afghanistan.

Elsewhere it is less formal and the threat has been more differentiated and diffused with key al-Qaeda franchises operating in Iraq, Yemen and associated groups in Africa and elsewhere.

This has involved military action - notably US drone strikes and activities by local military forces.

But it has also had many other aspects linking elements of both counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism.

- Published14 September 2014

- Published13 September 2014

- Published11 September 2014

- Published11 September 2014