Berlin leaves divisions behind as Wall's traces vanish

- Published

Chris Hadfield's picture from space clearly shows the yellower lighting in East Berlin

A year ago the Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield sent down from space an image that was both beautiful and astonishing.

His picture of Berlin, taken from hundreds of miles above the Earth, was that of a city divided.

The West glowed in a whitish colour, the East was yellowish - and the dividing line looked suspiciously like that of the infamous wall which had once cut the city in two.

A divided Berlin? Twenty-five years after the wall came crushing down to mark one of the happiest days in the city's history?

From less than 200 miles above the Earth that dividing line is hardly visible.

In fact, Berlin has done away with the wall so thoroughly that those wanting to mark the anniversary needed to rebuild the monument. It doesn't run through a barbed wire death strip any more but a huge mall on Potsdamer Platz.

Today, the guard tower overlooks H&M and a lingerie boutique.

An original East German guard tower near Potsdamer Platz is now a tourist attraction

Part of Berlin is being temporarily divided to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall

And yet, Commander Hadfield's picture from outer space speaks some truth.

Angela Merkel, a former East Berliner, may today be running the country, but the street lamps in the East are still sodium-vapour lamps with a yellower colour and the ones in the West are still fluorescent lamps with a whiter colour.

In the East people still read Berliner Zeitung, while the West reads Tagesspiegel.

One half roots for Hertha BSC, the other for FC Union, the football team from the East.

The income gap is closing, but it is still exists. In those exciting weeks 25 years ago, West Berliners went rural, East Berliners went commercial.

One half longed for a countryside from which they had been cut off for 30 years and the others for a more urban, less drab environment. Soon, they returned to their old neighbourhoods and their old ways of life.

Berlin, perhaps because it has seen and suffered so much, is a complacent city.

The East Berliners approached unification perhaps with a more pride than the rest of their country.

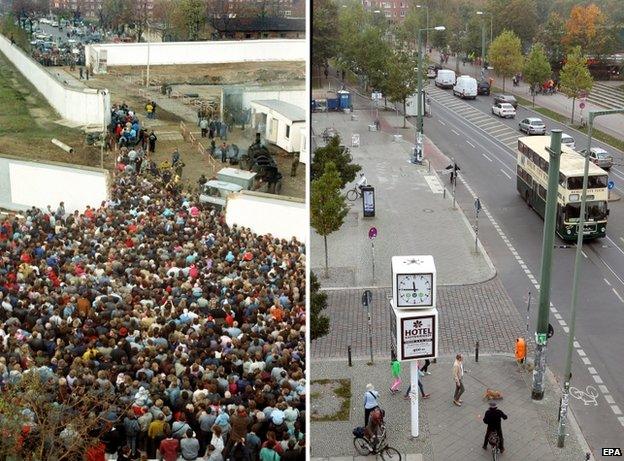

Bernauer street on 10 November 1989 (L) as crowds push through the wall and (R) the same street today

East Berlin had been the country's capital, and it is still home to a multitude of Communist Party and Stasi cadres, the last stalwarts of the old system.

Just like West Berlin, it was a highly subsidised social entity - both parts were propped up as showcases of their respective political systems.

This fed into a sense of importance on both sides of the wall, even before it collapsed, which their West and East German compatriots found at once off-putting and attractive.

The union worked because Berlin, traditionally a working-class city, was able to deal well with the remnants of the East German establishment and the post-communists' election successes in the 1990s.

No wonder, then, that it was Berlin where one of the first coalition governments involving the post-communists was formed.

Checkpoint Charlie (L in 1968) marked the border between the Soviet and American sectors and (R) in 2009

West Berlin, for many years an island in the sea of socialism, had always lacked Munich's or Hamburg's bourgeois elites. And even today the unified Berlin retains more of its East German legacy than most of the rest of the country.

At the same time, none of those who flocked to Berlin after 1989 were too worried about the city's past.

The 20-year-olds from Stuttgart and Dublin, the EasyJetters, the DJs, the artists, the fly-by-night real estate cowboys, the start-up financiers, the unemployed academics from Spain, they didn't concern themselves with the wall or the pain it had inflicted upon the city.

They brought a different and more innocent geography to the city.

To them the past, divided in East and West, was never more than the backdrop for their big party, fascinating but as unreal as The Third Man.

The throngs of young Israelis moving to Berlin and staging gay, "meshugge" (crazy) parties seem to indicate that Hitler's old haunt has finally turned the page.

Berlin Mayor Klaus Wowereit coined the phrase "poor, but sexy" for Germany's reunified capital

Eventually, the former East and West Berliners adopted that view of their city.

If everybody else is gushing about the exciting, unique new Berlin, why quibble with that? Why keep harping upon the past?

The newcomers allowed the locals to adopt a new narrative of their own city. And they did.

Berlin became a work in progress, hyped by its officials as the home of the future and brought down again by the uncouth Berliners themselves and their charming lack of ambition - to them a strip of lawn, a sausage and a beer amounts to an afternoon well spent.

Clearly that has a global appeal. Twenty-five years after the fall of the wall, Berlin is poor, but sexy, as outgoing Mayor Klaus Wowereit once said.

It is a provincial metropolis, a cultural playground, and this time it is being subsidised by those who are drawn to it and its allure.

Soon more time will have elapsed since the fall of the wall than the wall actually lasted. Yet, the social, cultural and political differences between East and West Berlin are still detectable.

They don't matter so much, however, because the city has found a different urban narrative. And, also, they don't matter so much, because Berlin has always been a city where differences mattered less than elsewhere.

Moritz Schuller is opinion page editor at Tagesspiegel in Berlin.

Berlin at a glance

Population 3.5 million approx.

Foreigners 372,300

Unemployment 10.8%

City reunified 9 November 1989

German parliament moves from Bonn to Berlin 19 April 1999

German government moves to Berlin 26 June 1999

Berlin's Brandenburg Gate in December 1989 (L) with East and West German policemen and (R) today

- Published3 November 2014

- Published30 October 2014

- Published15 October 2014

- Published15 March 2018