A new government brings hope of change in Afghanistan

- Published

The Afghan people are waiting to see if their new president keeps his election promises

Optimism - not a word you have heard a lot in Afghanistan of late.

But in Kabul right now, you hear it.

Maybe it is because there is a deep sigh of relief that the country has survived a months-long political crisis over a presidential election torn by fraud and two powerful camps adamant that they had won.

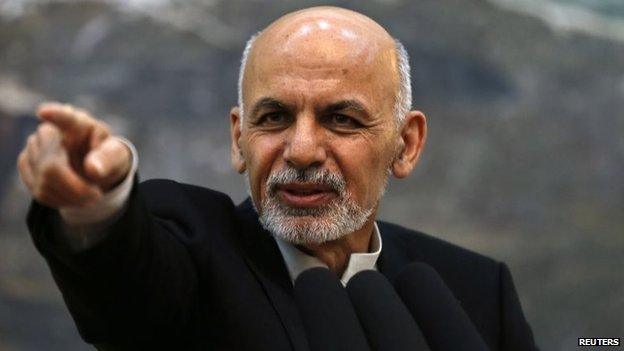

On Kabul roundabouts, alongside the huge billboards of mujahideen leaders and commanders assassinated through the years, official hoardings that announced Hamid Karzai's presence have been replaced by President Ashraf Ghani.

Even that is more than cosmetic in a country where power has rarely transferred peacefully.

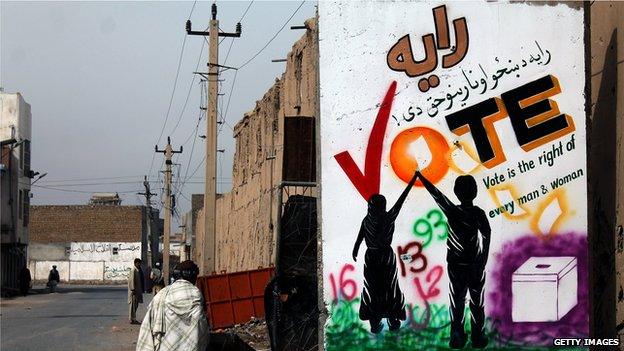

Some voices still warn of a "legitimacy crisis" over the final power sharing deal between President Ghani and Abdullah Abdullah which seemed to render a massive voting exercise irrelevant.

Critics say the unity deal between the rival presidential candidates made voting irrelevant

Maybe there is optimism because this is another new beginning in a country where all too many new starts have led to yet another time of violence and hardship.

"We can't afford not to be optimistic after living with war for so long," an Afghan friend tells me.

A new political order is being installed and the country awaits promised action on many pressing challenges confronting this nation as foreign troops pull out, aid levels drop and Taliban attacks are on the rise.

Vibrant election

This time the generation that has come of age in the last decade of international engagement have new weapons to hold their leaders to account.

Among them, a website called Sad Roz is tracking the progress of political pledges, external made in the heat of vibrant election campaigns and urges Afghans to "submit a missing promise".

Kabul's chattering classes swap stories of a new president who sleeps only three hours a night, devours every document searching for essential details and schedules his diary so tightly that a senior official who arrived five minutes late was told he had missed his moment.

President Ghani's meetings with allies and old rivals are hot topics in Kabul

Afghans, with a brand of humour honed through decades of war, tell tales of turbaned tribal elders ushered out of the presidential office, protesting their tea is still warm.

"I'll give you an important piece of information, " one of his aides whispers to me. "President Ghani is meeting Chief Executive Officer Dr Abdullah every week, one on one, for more than an hour to discuss important matters."

In animated conversation, Afghans discuss who sides with Ghani, who with Abullah, and there are still those who say they remain with Karzai - a player who will still remain in the game.

But the transition is underway.

For the first time for as long as anyone can remember, there is an office of the First Lady of Afghanistan.

First lady Rula Ghani: "I would like to give women out there the courage and the possibility to do something about improving their lives"

Lebanese-born Rula Ghani is now in "listening mode" receiving delegations from all walks of life.

Ashraf Ghani's public acknowledgement of his wife during his inauguration was mentioned to me by many Afghan women during a visit to the capital.

A simple gesture sent a powerful signal in a deeply conservative culture.

"He recognised that women exist," one Afghan aid worker exclaimed.

And yet, whatever change will come will still sit, sometimes uneasily, with the stubborn realities of more traditional ethnic based politics.

Anxious questions

On a not too unusual day in Kabul, traffic was slowed along the main avenue of government buildings by gaggles of turbaned men in long cloaks sauntering down the road and young men in pickups revving their engines outside a well guarded gate.

Visitors from northern Uzbek areas had come to call on their leader - Uzbek strongman Abdul Rashid Dostum who now presides as vice president, and has his own promises to keep.

Afghan optimism is still wrapped in anxious questions.

Young Afghans who threw their energies and aspirations into the presidential race now ask whether the political space will stay open for them, or if they will be sidelined by men of guns and greed.

Supporters of rival camps wonder which posts in the new cabinet will go to which side, and who will take up the jobs.

For all the exhilaration of a new beginning, the fundamentals of the old have not changed.

Many Afghans hope that the new government can bring change despite the challenges

Afghanistan is still a country on the brink of bankruptcy, threatened by instability.

But in the absence of clear evidence about which way this new beginning will turn, some Afghans allow themselves to hope this chapter will be different.

In Afghanistan, any optimism is cautious, but for the moment it is there.