Peter Greste freed: How Egypt jailed al-Jazeera reporter

- Published

Peter Greste (R) alongside his colleagues, Mohamed Fahmy (C) and Baher Mohammad, in court

It was meant to be a routine three-week deployment from his base in Nairobi to cover the ongoing see-saw that is Egyptian politics.

Peter Greste arrived in Cairo in December 2013. Two weeks later, his room in the Marriott hotel was raided and, along with two colleagues from the al-Jazeera TV news network, Mohamed Fadel Fahmy and Baher Mohammad, he was thrown into the notorious Tora Prison.

They were not the first journalists from al-Jazeera to feel the force of the Egyptian state.

During the second half of 2013, a number of reporters, cameramen and producers from the Qatar-based media organisation had been arrested, beaten up and had their equipment confiscated.

But most were held for a short time before being released.

Muslim Brotherhood

The army-backed regime of interim President Adly Mansour regarded al-Jazeera as sympathetic to the Muslim Brotherhood, which had been deemed a terrorist organisation after Egyptian President and Brotherhood member Mohamed Morsi was deposed by the military in July 2013.

The authorities accused Greste and the others of falsifying news and having a negative impact on overseas perceptions of Egypt - but it was clear the underlying accusation was one of backing the Muslim Brotherhood.

"How do you accurately and fairly report on Egypt's ongoing political struggle without talking to everyone involved?" Peter Greste wrote.

"We had been doing exactly as any responsible, professional journalist would - recording and trying to make sense of the unfolding events with all the accuracy, fairness and balance that our imperfect trade demands."

Key dates

29 December 2013: Peter Greste, Bader Mohamed and Mohammed Fadel Fahmy arrested

February 2014: Put on trial in Cairo on terrorism-related offences

23 June: Convicted and jailed for seven to 10 years

There were hopes that Greste and his colleagues would be released quickly. The campaign at first was low-key - discussions behind the scenes - but it soon became clear that the three were in for the long haul.

As the days and weeks went by, the clamour for the men's release grew.

Silent protests against the verdict were staged by news organisations around the world

Members of Peter Greste's family shuttled between Australia and Cairo, lobbying for his release.

There were protests around the world from governments, the United Nations and fellow journalists.

From prison, Greste wrote:

"Our arrest doesn't seem to be about work at all, it seems to be about staking out what the government here considers to be normal and acceptable. Anyone who applauds the state is seen as safe and deserving of liberty. Anything else is a threat that needs to be crushed."

Cramped cell

Before one court hearing in February, Peter Greste's brother, Andrew, described the cell his brother and the two others were being held in:

"It was approximately 3m (10ft) square. There's a single bed on one wall and a double bunk bed on another wall. Then there's a small ablutions, you know, screened-off toilet area. So conditions are, you know, pretty tough."

After six months, the men were put on trial.

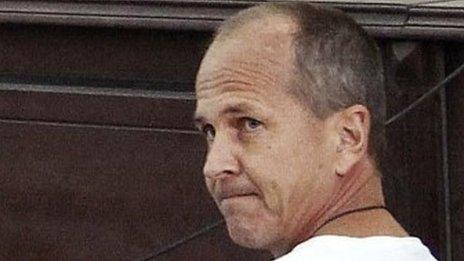

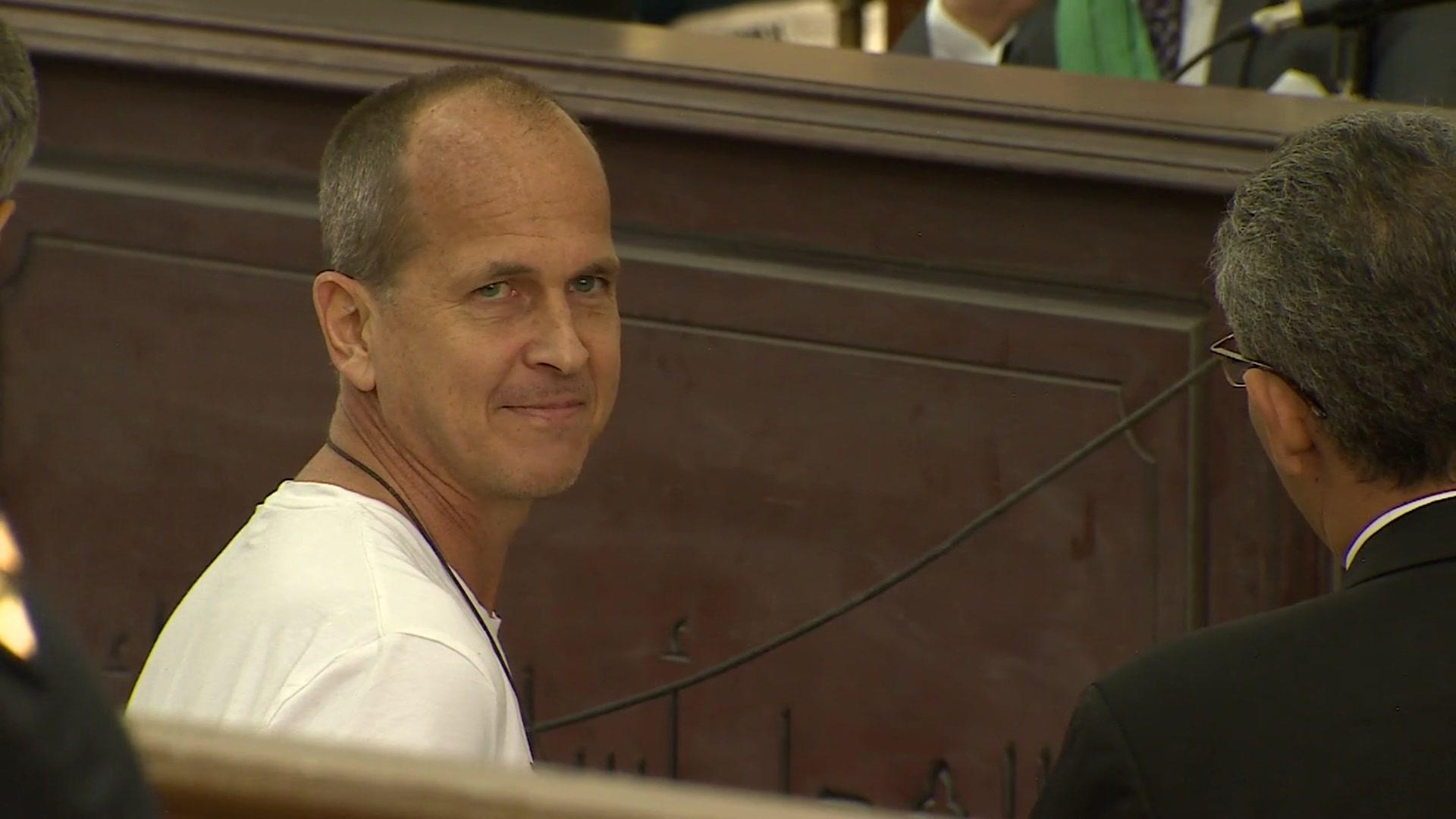

The journalists were detained inside iron mesh cages throughout the trial

Striking images of Greste and his colleagues in a steel cage inside the court room were beamed around the world.

Then, in late June, came the verdict - all three men were found guilty. Peter Greste and Mohamed Fadel Fahmy were sentenced to seven years in prison; Baher Mohammad got 10 years.

Peter Greste's family was devastated.

Both brothers were in court for the verdict.

"I'm just stunned," said Andrew Greste, as police jostled reporters from the courtroom. "It's difficult to comprehend how they can have reached this decision."

In Australia, Greste's father, Juris, said only: "That's crazy, that's crazy, that's absolutely crazy,".

The international outcry was substantial.

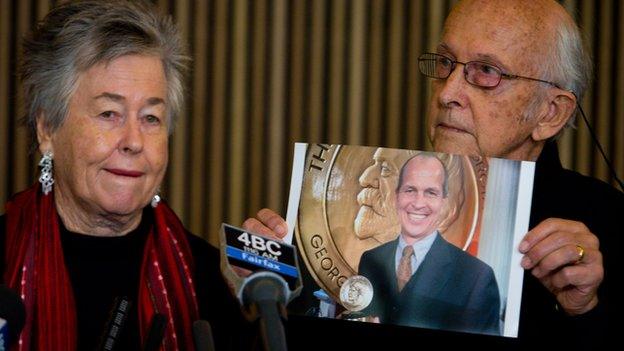

Peter Greste's family appealed directly to President Sisi to release their son in November

US Secretary of State John Kerry described the verdicts as "chilling and draconian", a day after he had met newly-elected President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi and the United States had restored economic and military aid to Egypt.

The human rights group, Amnesty International, called the decision a "dark day" for press freedom.

It said: "The prosecution failed to produce a single shred of solid evidence linking the journalists to a terrorism organisation or proving that they had 'falsified' news footage."

But Egypt's leaders were unmoved. President Sisi said he would not interfere with the judicial process.

And so the three men began the long process of preparing their appeals.

Speculation grows

But at the beginning of November, there was a chink of light in the case.

President Sisi issued a decree permitting convicted foreigners to serve their sentences in their own countries. At that point, Peter Greste's parents gave the announcement a cautious welcome.

Speculation grew over whether the regime was considering a change of heart as the January date for the appeals to be heard drew closer.

In the event, appeals judges ordered a retrial, with the prosecution acknowledging that there were major problems with the verdicts.

Then, after a day of rumours, Peter Greste was deported on 1 February, while the fate of his colleagues remained unclear.

The Egyptian authorities may be hoping that they can begin to rebuild their reputation internationally.

But human rights groups are swift to point out that thousands of political prisoners remain incarcerated in Egypt's jails. Where, they ask, is the outcry for them?

- Published21 November 2014

- Published25 July 2014

- Published31 March 2014

- Published23 June 2014