The rise of IS - and how to beat it

- Published

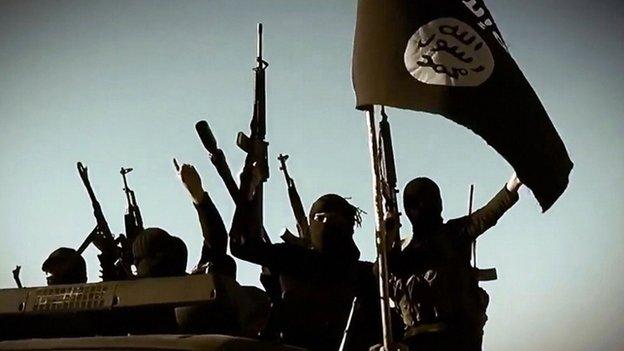

IS militants control a huge swathe of Iraqi and Syrian territory

To make sense of the sudden rise of Islamic State (IS) and its territorial gains in Iraq and Syria, it is important to place the organisation within the broader global jihadist movement.

In particular, we must examine the links with the organisation out of which it grew, al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia, also commonly known as al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI).

Between 2003 and 2010, the power vacuum and armed resistance triggered by the US-led invasion and occupation of Iraq, as well as the dismantling of Saddam Hussein's former ruling Baath party and the Iraqi army, provided a fertile terrain for AQI's growth and an opportunity to infiltrate the increasingly fragile body politic.

However, AQI's rapid surge did not go uncontested and two events particularly threatened its expansion.

In 2006, the Salafist-jihadist group's conflict with Sunni Arab tribal leaders, who were angered by the reign of terror and extremism its imposed in their provinces, triggered an internal war that led to formalised co-operation between local tribes and the Americans.

In that same year, AQI's founder and chief, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, was killed by the US, marking a turning point of retrenchment and decline for the militant organisation.

A transitional period ended with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi's nomination as AQI leader in 2010.

Military experience

Baghdadi's rise to power coincided with a highly polarised political situation in Iraq, where central government policies marginalised and undermined the Sunni community.

At the time, Prime Minister Nouri Maliki's sectarian-based policies were also seen to be the result of increasing Iranian influence, which allowed Baghdadi to position his restructured organisation as the vanguard of the Sunnis against the Shia-based regime in Baghdad.

Baghdadi's command led to shifts in the organisation's modus operandi on various levels.

An intra-jihadist war between IS and al-Nusra Front has left thousands dead

He oversaw the complete restructuring of the military apparatus by recruiting experienced and skilled officers from Saddam's disbanded army, particularly the Republican Guards, who turned IS into a professional fighting force and a potent killing machine.

According to knowledgeable Iraqi sources, Baghdadi relies on a military council made up of eight to 13 former army officers.

He was also was one of the few top jihadists to recognise early on the significance of the Syrian crisis and the potential benefits that could be gained from the political chaos there. In fact, the Syrian and Iraqi conflicts have allowed Baghdadi to rebuild AQI into a powerhouse.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi: A mysterious leader:

Not much is known about Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of Islamic State (IS), and it is difficult to disentangle myth from reality.

The Iraqi's followers claim he has a doctorate from the Islamic University of Baghdad, with a focus on Islamic culture, history, Sharia, and jurisprudence.

This they use to portray him as a man of letters, theologically learned, and amply qualified to be a caliph or leader of the global Muslim community, or Ummah.

Baghdadi's propagandists even paint an image of him as a pious and bookish teen destined to do great deeds.

However, people who knew him draw a dramatically different sketch of an ordinary man - born in the city of Samarra, in what is known as the "Sunni Triangle" to the north of Baghdad - hot-tempered and confrontational, shifting from one ideological pole to another.

Regardless of Baghdadi's personal story, one thing is certain: his journey and migration towards self-radicalization and militarization took place after the US occupation of Iraq and his imprisonment in American military prisons there.

He was arrested by US forces and detained in Camp Bucca near Umm Qasr between 2004 and 2005, a facility in southern Iraq, on charges of being a Sunni "foot soldier".

This is where he was able to meet jihadist militants of al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) and to build a broad network of like-minded religious extremists.

In Camp Bucca, Baghdadi also encountered officers of Saddam Hussein's disbanded army, prompting an unholy union between jihadists and former members of the Baath party.

When the Americans withdrew from Iraq in 2011, AQI included a few hundred followers at most - now Islamic State's mini-sectarian army numbers between 17,000 and 32,000 fighters.

By contrast, at the height of its power in the late 1990s, al-Qaeda Central mustered only 1,000 to 3,000 fighters, a fact that shows the limits of transnational jihadism and its small constituency compared with the "near-enemy" or local jihadism of the IS variety.

Intra-jihadist war

In 2011, Baghdadi sent his operative Abu Mohammed al-Julani to Syria to organise jihadist cells in the war-torn country, which eventually led to the establishment of al-Nusra Front - al-Qaeda Central's official Syrian affiliate.

In addition to Syria offering a fertile ground for the supply of arms, men, resources, the disintegration of the country's social fabric and political system also provided motivation and inspiration for IS jihadists.

Cracks at the centre of the group's leadership surfaced in 2013.

Baghdadi called for an Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Isis or Isil), which would see the merging of AQI and al-Nusra.

Julani rejected the merger, a move backed by al-Qaeda's overall leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, to whom Julani pledged allegiance.

An intra-jihadist war between IS and al-Nusra killed thousands of skilled fighters and exposed a fierce power struggle between Baghdadi and his former mentor - Zawahiri.

For now, Islamic State has taken operational leadership of the global jihadist movement by default, eclipsing its parent organisation.

The scale and intensity of its brutality, stemming from Iraq's blood-soaked modern history, far exceeds either of the first two jihadist waves of recent decades.

Its viciousness reflects the bitter inheritance of decades of Baathist rule that tore apart Iraq's social fabric and left deep scars that are still festering, as well as the ruralisation of this third jihadist wave.

Whereas the two previous jihadist waves had leaders from the social elite and a rank-and-file mainly composed of lower-middle-class university graduates, Islamic State's cadre is rural and lacking in both theological and intellectual accomplishment.

Social decay

IS has blended itself with poor, rural Sunni communities and established a potent social base.

These disenfranchised areas represent social hotbeds of contention as decades of social decay and state corruption have left the youth disillusioned with the political establishment.

Mosul has been a fertile recruiting ground

IS, for example, has targeted the poorest districts of Mosul and Raqqa, the two most populous cities that it controls in Iraq and Syria, and recruited soldiers and policemen, supplying them with weapons, salaries or even empowering them by setting up a "patrol" force.

The group's swift military expansion stems from its ability not only to terrorize enemies but also to co-opt poor local Sunni segments, using economic incentives and networks of patronage and privilege, such as protection of contraband trafficking activity and a share of the oil trade and smuggling in eastern Syria.

In many ways, what we are seeing is not just creeping Sunni-Shia sectarianism but a socio-economic warfare.

At the heart of the so-called Arab Spring is an uprising of the agrarian and urban poor.

One of Islamic State's strengths is its ability to target the most vulnerable sections of the population and manipulate anger against a state system that fails to address some of its citizens' most basic needs.

The influx of foreign fighters from the Arab world and beyond is also a proof of the strength of the IS counter-narrative and its ability to turn foot soldiers into loyal killing machines ready to give their life for the group.

Islamic State's sophisticated outreach campaign appeals to disaffected Sunni youth around the world by presenting the group as a powerful vanguard movement capable of delivering victory and salvation. It provides them with both a utopian worldview and a political project - resurrecting the lost caliphate.

The group adheres to a doctrine of total war, with no constraints. It disdains arbitration or compromise, even with Sunni Islamist rivals.

Unlike al-Qaeda Central, it does not rely on theology to justify its actions and has not seen the need to lay out a theological or religious manifesto: the group has after all already established a de facto caliphate and controls a land-mass stretching across Syria and Iraq that is as big as the UK, where five million people live.

Feeling of despair

However, IS is much more fragile than Baghdadi would like us to believe.

His call has not found any takers among either top jihadist preachers or leaders of mainstream Islamist organisations, while Islamic scholars - including the most notable Salafist clerics - have dismissed his declaration as null and void.

As long as IS is on a winning streak, it can get away with its poverty of ideas and widespread opposition from Muslim public opinion: it promises utopia and delivers by winning.

The challenge facing the group is that once its advances are checked, its lack of a cohesive ideology will speed up its social decay.

IS has targeted disfranchised Sunni communities by manipulating deep-seated feelings of despair

During my conversations I have had with Iraqi tribal leaders, many acknowledge that their sons join the IS caravan not because of its Islamist ideology but as a means of resistance against the sectarian-based central authority in Baghdad and its regional patron, Iran.

The group's swift capture of most of the so-called "Sunni Triangle", suicide bombings - particularly targeting of the Shia - and anti-US rhetoric appeal to the Sunni youth who feel that the country had been humiliated and colonised by the US with Iran's backing.

It is no wonder then that thousands of Sunni Iraqis fight under the IS banner without subscribing to its extremist Islamist ideology.

Perhaps one of the most worrying aspects of Islamic State's targeting of disfranchised Sunni communities is its manipulation of a deep-seated feeling of despair and lack of hope that spread throughout the region and triggered the large-scale popular Arab uprisings of 2010-2012.

In the Middle East, ordinary people have fought for their rights, freedoms and self-determination without necessarily using violence for decades.

In its intent on propagating the belief that savagery is more effective as a mobilization tool than civil resistance against local rulers and foreign-inspired and imperialist stratagem, IS only repeats the usual adage used by dictatorships in the region, which legitimises autocracy in the name of authenticity.

By portraying itself as the only alternative to a broken and corrupt political system, IS is also taking back agency from the people.

By denying the power and central role of civic movements in bringing about change, groups such as IS and al-Nusra use a narrative that equates resistance with indiscriminate and cruel violence.

Lasting legacy

In this sense, one of Islamic State's most harmful lasting impacts in the region is its strategy of neutralizing or expunging civilian-driven strategies that could forge not only national but regional transformation.

Accordingly, the key to weakening IS lies in working closely with Sunni communities it has co-opted, a bottom-up approach that requires considerable material and ideological investment.

The most effective means to degrade IS is to dismantle its social base by winning over hearts and minds, a difficult and prolonged task, and to resolve the Syria conflict that has given IS motivation, resources and a safe haven.

Indeed, there is no simple or quick solution to rid the Middle East of IS because it is a manifestation of the breakdown of state institutions, dismal socio-economic conditions and the spread of sectarian fires in the region.

IS is a creature of accumulated grievances and of ideological and social polarisation and mobilisation a decade in the making.

Fawaz A. Gerges is a professor of international relations and Middle Eastern politics at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is author of several books, including "The New Middle East: Social Protest and Revolution in the Arab World."

- Published11 August 2014

- Published28 March 2018

- Published17 June 2014

- Published9 September 2014

- Published30 June 2014