How Palestinian democracy has failed to flourish

- Published

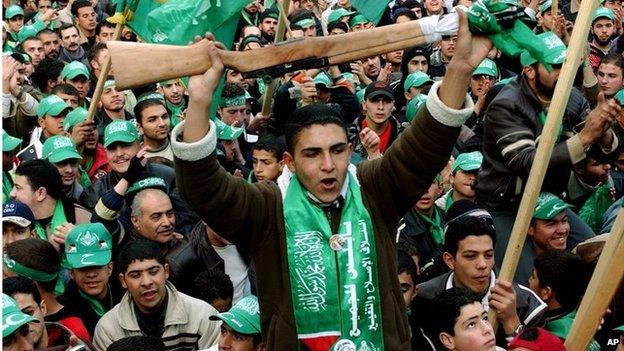

Hamas was elected at the ballot box but found itself isolated by parts of the international community

In the main market of Qalqilya there is still the smell of spices and all the hustle and bustle that I remember from my first visit to the West Bank town 10 years ago.

But attitudes towards democracy and enthusiasm for elections have dramatically changed here since then.

"We used to hear a lot about democracy from all around the world," says Ahmed, a stallholder, as he bags stalks of dried thyme. "But we found the theory works better than the practice."

In 2005, after the Palestinian Islamist militant group, Hamas, participated in elections for the first time, it took over several local councils, including Qalqilya.

Voters we met in the town back then said that the former officials from the mainstream, secular Fatah faction had been corrupt. They expected a religious party to be cleaner and do a better job of providing basic services.

For similar reasons, Hamas went on to win a decisive victory in the Palestinian legislative elections in January 2006 - winning 74 of the 132 seats.

Turnout was high at 78% and international monitors said the vote was largely free and fair.

But the result was met with dismay by Israel and Western donors - which prop up the Palestinian Authority (PA).

They refused to deal with Hamas politically unless the group renounced violence and its commitment to the destruction of Israel. Funds to pay for vital services were stopped or diverted.

While a new unity government was briefly set up a year later, it was soon dismissed amid bitter infighting between Fatah and Hamas.

This led to the political bifurcation of the West Bank - where Fatah reasserted its authority - and the Gaza Strip - where Hamas ran a rival administration.

"We're only allowed democracy if the West likes our choices," comments one Qalqilya shopper as he reflects on this troubled political history. "They supported us when we went to the ballot boxes but did a u-turn when Islamists won."

Occupation obstacle

When I visited the Qalqilya municipal offices back in 2005, my BBC team came across British diplomats as they struggled to deal with the changing political reality and met new Hamas officials.

However, the Hamas era here did not last long. Locals quickly lost faith in the movement, which had little political experience and little outside support.

Palestinians say they cannot function as a proper democracy while under Israeli occupation

Now a Fatah mayor is back in charge. People in Qalqilya voted for Othman Dawood in the last local elections that took place in the West Bank in 2012.

Yet he complains that his powers to tackle his town's economic hardships are restricted.

"We're a democratic society. It's in our blood," Mr Dawood says. "We have long had different political factions and ideologies. There are public consultations. But in the end we cannot have a real democracy under Israeli occupation."

The mayor points to a large map on the wall that shows Qalqilya virtually encircled by the separation barrier that Israel has built in and around the West Bank. The barrier in general is made up mainly of chain-link fence topped with barbed wire, but in some areas consists of 8m- (25ft-) high walls.

Fatah officials Walid Assaf (left) and Othman Dawood, in front of aerial photo of Qalqilya

Israel says the barrier is needed to protect it from Palestinian attackers but it also restricts the movements of ordinary Palestinians and cuts them off from profitable agricultural land.

"The biggest disagreement between the Palestinian political factions is about how to end our conflict with Israel and establish an independent Palestinian state," Mr Dawood says. "Hamas wants a military solution, Fatah a negotiated solution. We are divided and this makes us weak."

Expired mandate

Although a new unity deal was struck between Hamas and Fatah last April, so far their technocratic government has failed to pave the way for promised elections across Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem, the latter annexed by Israel in a move not recognised internationally.

Many ordinary Palestinians have become cynical about the entire political process and the ability of any faction to effect meaningful changes on the ground.

BBC Democracy Day

Democracy Day takes place on Tuesday 20 January, across BBC radio, TV and online

A look at democracy past and present, encouraging debate on its role and future

2015 marks the 750th anniversary of the first parliament of elected representatives at Westminster

It also sees the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta - a touchstone for democracy worldwide

Go to the BBC News website's Democracy Day page, external, for analysis, backgrounders and explainers on the debate

Adding to this is the sense that most of their leaders now have questionable mandates to govern.

Mahmoud Abbas won a four-year presidential term in elections in 2005 - a vote that was boycotted by Hamas. He later extended this for a further year and has since relied on the powerful umbrella group the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) for recognition as president.

Hamas and Fatah agreed to form a unity government but the rift is still deep

Members of the Palestinian Legislative Council - the Palestinian parliament - saw their terms expire in 2010.

The head of the Palestinian Central Election Committee, Hisham Kuhail, says his body remains ready for new polls - if only arrangements can be made.

"For any upcoming election there must be internal agreement - between Fatah and Hamas to co-ordinate in the West Bank and Gaza," he says. "Then we must rely on the Israelis making concessions in East Jerusalem."

In 2006 Israel banned Hamas, which it regards as a terrorist organisation, from campaigning in East Jerusalem and blocked its inclusion on ballot papers in the sector.

"Every year we renew the electoral roll," Mr Kuhail goes on. "We remain 100% ready for any call."