Militants, migrants and the Med: Europe's Libya problem

- Published

The Italian authorities have been struggling to cope with the migrant surge

Islamic State militants in Libya have vowed to attack Europe. Meanwhile, boatloads of migrants flee the collapsing state for European shores. Could the Mediterranean migration mask an influx of militants?

Italy and Egypt have warned that Islamic State (IS) militants could hide among thousands of migrants rescued by European patrols.

Both countries are troubled by the situation in Libya and have an interest in influencing it. However, neither has given any evidence to support its warnings.

The migrants are mostly from Syria and sub-Saharan Africa. The idea that they pose a threat evokes a vicious logic at odds with humanitarian imperatives: refugees bring conflict, as conflict breeds refugees.

What threat do the migrant boats pose? And what - if anything - can be done about it?

More migrants than ever before are attempting the sea crossing from Libya

Last week, Libyan militants allied to IS released a video that appeared to show the beheading of 21 Egyptian prisoners. The choreography echoed videos shot in Iraq and Syria.

However, instead of desert, the prisoners were positioned on a beach, against the grey Mediterranean Sea.

Addressing the camera, a masked man promised attacks in Europe. "And now we are south of Rome, on the land of Islam, Libya," he said, "sending you another message."

The claims

The video is thought to have been filmed near Sirte, a Libyan coastal town where Islamic State has gained a foothold. A few miles off that coast last week, an Italian operation rescued some 2,000 migrants from stormy waters.

As one of the empty vessels that had carried the migrants was being towed away, a speedboat swept off the Libyan shore. The men aboard it were armed with assault rifles and, according to Italian officials, they wanted their boat back.

The confrontation was the latest sign that some of the armed groups thriving in the Libyan chaos are also involved in human-trafficking.

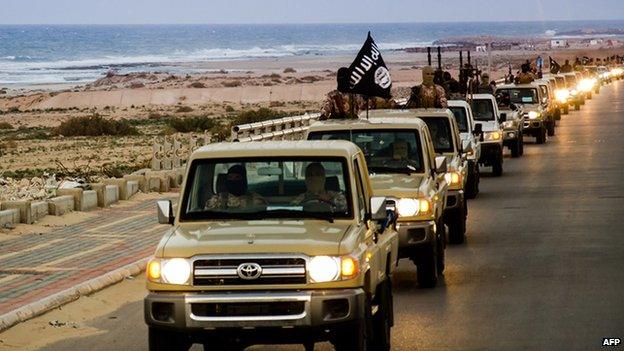

Islamic State fighters have gained a foothold in the Libyan town of Sirte

For the militias, the profit to be made from smuggling migrants is a good reason to enter the trade. For the local franchisees of Islamic State, there could be further incentives.

The Mediterranean is their gateway to Europe, according to a document published online in January, purportedly by an Islamic State sympathiser in Libya.

"The southern Crusader states... can be reached with ease by even a rudimentary boat," says the document, widely quoted in the British press after it was translated by the Quilliam Foundation, external, a counter-extremism think tank.

However, the Foundation says the authenticity of the document cannot be confirmed and its claims must be treated with caution - at most as propaganda rather than mission statement.

Islamic State may already be using migrant routes from Turkey, according to a BuzzFeed report, external last month. The report cites traffickers as saying that the fighters travel among asylum seekers aboard cargo ships.

Last week, Egypt's ambassador to the UK, Nasser Kamel, told the BBC it could be just a matter of time before the militants struck Europe by sea.

"[There are] boat people who go for immigration purposes and try to cross the Mediterranean," he said. "In the next few weeks, if we do not act together, there will be boats full of terrorists also."

Egypt's aim

Egypt says its fighter jets have bombed Islamic State targets in Libya

Egypt shares a porous border with Libya, and is fighting a homegrown Islamist insurgency. It has backed an anti-Islamist faction in Libya's civil conflict, launching air strikes against what it says are Islamic State targets there.

"Egypt is particularly keen to amplify the threat of Islamic State in Libya as it is desperately seeking approval for international intervention in the country," says Alison Pargeter, an analyst focusing on Libya for the Royal United Services Institute, a British defence think tank.

She says the government in Cairo is frustrated that most European nations have pushed for a political rather than military solution to the Libyan crisis.

Italy, meanwhile, bears the brunt of the maritime migration and has shouldered the burden of the rescue operation. The government is under fire from activists for not doing enough for the migrants - and from far-right politicians for doing too much.

2014 - Migrants in numbers

At least 218,000 reached Europe by the Mediterranean Sea

Italy received more than 140,000 of the arrivals

3,500 people died attempting the journey - compared with just over 600 in 2013

Source: The UN refugee agency

Foreign Minister Paolo Gentiloni was quoted by Ansa news agency last month as saying that there was a "considerable risk of terrorists infiltrating immigration flows".

In its latest statements, the Italian government has sought a middle ground: emphasising that the boats represent a humanitarian crisis while admitting that the terror threat cannot be ruled out.

Italy wants a robust international response to the crisis in Libya, although it does not share Egypt's enthusiasm for another armed intervention.

Italy used to be the colonial power in Libya. It now depends on Libyan oil for its energy needs, while Libya depends on Italy for the revenues.

According to veteran Italian journalist Andrea Purgatori, the migrant boats are not so much a terror threat as pawns in "a sort of game" - a means for Libyan forces to steer Italian involvement in their country.

Libya's oil facilities have been hit by the fighting between rival militias

Ms Pargeter says the claims of militants using migrant boats "seem rather overblown and exaggerated". Islamic State is a growing threat in Libya - but, she says, "its operational capacity is limited".

"It is a relatively small group... and is up against an array of other competing militias and armed groups, including those of a militant Islamist bent that are far more powerful."

'Plausible risk'

As such, the warnings from Egypt and Italy, as well as recent statements from militants, do not amount to evidence of a threat. The European Union's border agency, Frontex, and its police force, Europol, told the BBC they could not comment on the claims.

However, no evidence of an imminent threat does not mean that the threat does not exist.

Militants may be tempted by clandestine sea routes to Europe, such as those followed by some migrants and drug-traffickers, says Christian Kaunert, a professor at Dundee University who specialises in European terrorism and refugee issues.

A secret crossing would be especially appealing to European jihadists returning from the Middle East, as it sidesteps the tight screening now in place at airports.

Italy has emphasised that the migrant boats are, above all, a humanitarian crisis

The risk of such infiltration, Mr Kaunert says, "is plausible - but whether it's absolutely credible is difficult to assess because by definition, when those boats come in, they go unnoticed."

Most of the migrants leave Libya on conspicuously overcrowded boats, unfit for the crossing. They reach Europe by relying on coastal rescue missions to bring them ashore. Many also drown at sea.

For Islamic State, this may seem like an inefficient way of delivering fighters. But a group that has many recruits may be ready to lose a few en route, betting on those that eventually get through.

Nor does it need those surviving recruits to be particularly skilled. Where the objective is disruption and panic, sheer intent may be enough. The attackers in Copenhagen and Paris "didn't need an awful lot of military training", says Mr Kaunert, "just a certain ideological training".

Once ashore, migrants are held in detention centres while their asylum claims are processed. In theory, a militant could gain the right to remain in Europe by exploiting well-known flaws in the asylum process.

Governments determine asylum applications by comparing what they are told by the applicant with what they know of conditions in the country of origin. But applicants can lie, while governments are frequently accused of being ill-informed or biased.

Activists say migrants who are fleeing for their lives are unlikely to be deterred by the dangerous crossing

However, activists say demanding more evidence from asylum seekers would endanger genuine refugees.

"The burden of proof to establish that you are a refugee is a low one, [and] rightly so, as rarely would those fleeing for their lives be able to corroborate their evidence," says Lisa Doyle, head of advocacy at the Refugee Council, a British charity.

"Mixing the messages around our humanitarian responsibilities... with arguments around infiltration of terrorists is not helpful," she says.

Border controls and the bureaucracy of asylum are Europe's response to the conflicts that produce refugees. But they are not a solution to those conflicts. And in the face of the biggest global refugee crisis since World War Two, there are questions over whether they are even the best response.

Last year, almost 3,500 people died while trying to reach Europe by the Mediterranean Sea, according to the UN refugee agency. More than 200,000 migrants were rescued from the sea over the same period.

Attacks inspired by Islamic State have killed fewer than 25 people in Europe over the last year. None of the attackers were migrants.

- Published15 September 2014

- Published30 September 2014

- Published5 February 2015