Searching for light in war-torn Syria

- Published

Millions of people across Syria are now relying on international humanitarian aid

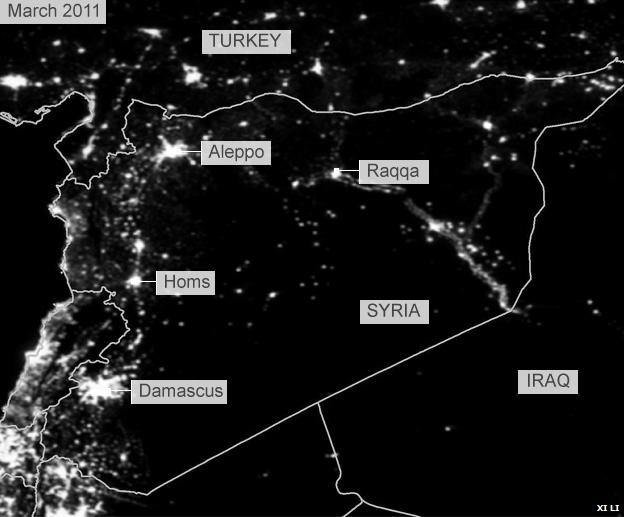

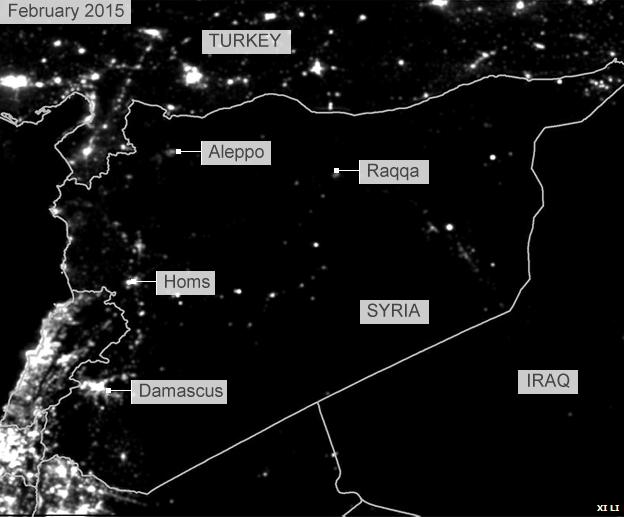

A dark shadow falls across Syria as a punishing war enters its fifth year.

It's not just that satellite imagery has revealed the night sky is 83% darker because so much infrastructure has been destroyed, and millions forced to flee their homes .

It's not just that UN Security Council resolutions - urging armed forces to protect civilians and allow greater access for humanitarian aid - have largely been ignored.

It's not just that Syrian leaders on all sides of a bitter and brutal divide still don't genuinely subscribe to the mantra that "there is no military solution."

None of their outside allies, providing military or moral or financial support, are pushing them to accept it either.

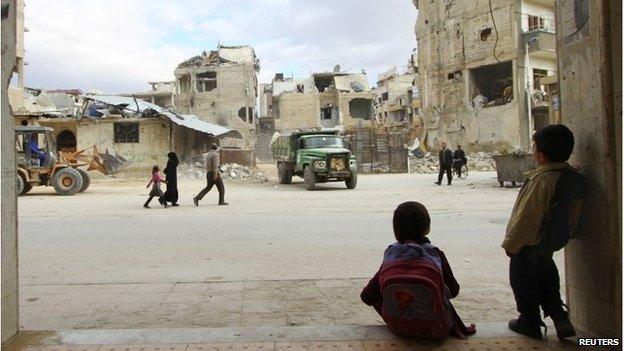

It's also that hope is draining from so many Syrians, no matter what side they're on, that this nightmare will be over any time soon. No-one expected it would last so very long and cost so very much.

You see it in the eyes of millions of Syrian children and exhausted parents, displaced from their homes, or forced into exile, who now realise their dream of going home, going to school, was just that - a dream.

You see it in the anguish of young educated Syrians who, four years ago, were stirred by the tantalising prospect of peaceful political change. They gambled almost everything, including their future, on this shimmering prize, and now anguish that they lost almost everything in return.

'Slim prospect'

"We have all the international institutions we need to resolve this crisis," Lord Michael Williams, a former Mideast envoy, recently told me with palpable regret.

President Bashar al-Assad says he still enjoys significant support in the country

He points to the experience of international efforts in the Bosnia war of the 1990s.

All available instruments of international intervention, including military force, and international justice in the form of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, were deployed in the name of humanitarian principles.

This week Lord Williams writes that when it comes to Syria, external "it is daunting to write that there is a slim prospect of international intervention, and if truth be told, even less of international justice".

Even humanitarian obligations under the 1951 International Refugee Convention are not being honoured.

"Western countries, with the honourable exception of Sweden, have taken fewer refugees from the Syrian war than almost any other conflict in the past 100 years," Lord Williams adds.

Germany also stands ahead of other Western nations with its pledge to take in 20,000 Syrians. Britain has agreed to accept 500, and has so far accepted less than 100.

'Not interested anymore'

Hence, there is the urgent question with its barely concealed anger: "What will it take?" That's the unprecedented banner headline of a statement signed by more than 20 heads of international agencies - including even UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon.

The UN's humanitarian envoy, Valerie Amos, who repeatedly implored a divided UN Security Council to do more, spoke in a recent interview of "a stain on the international community".

"It may take at least another five years," concedes another senior UN official involved in frustrating efforts to try to bring an end to this devastating downward spiral.

The worst East-West crisis since the end of the Cold War is now making it ever more difficult to achieve the kind of co-operation that allowed the US and Russia to at least reach a deal in 2013 on eliminating Syria's chemical weapons.

Washington's priorities now are the fight against the so-called Islamic State (IS) in Iraq and Syria, as well as critical negotiations with Iran over a nuclear deal.

"They're just not interested anymore," remarks a Washington-based Syrian activist, who has been shuttling between US government offices and rebel-held areas of Syria since the first years of this conflict.

"Syria doesn't have a Merkel and Hollande making this crisis a priority," comments Justin Forsyth, Chief Executive of Save the Children, in a reference to the dogged, if only partially successful, European efforts to resolve the crisis with Russia over Ukraine.

Growing pressure

The optimists say "if and when there is a nuclear deal" the West will then focus on working with Iran, arguably the Syrian government's most important ally, to put pressure on President Assad.

Aid agencies say 5.6 million children are in need of aid, a 31% increase since 2013

But for Tehran and Moscow, the ominous reach of IS forces, as well as the growing sway of the al-Qaeda-linked al-Nusra Front, only reinforces their view that to move against President Assad now is to move towards an even more chaotic future.

Many suspect Western governments also harbour this anxiety, even if they still insist President Assad is "part of the problem, not the solution".

"We will be prepared to look at other options when the time is right," one senior Iranian official told me late last year. "But now is not the time."

Western political and military leaders still talk about supporting the "moderate Syrian opposition" - even though forces armed by the West and some Gulf allies are steadily losing ground on the battlefield.

"We're coming under pressure to talk to al-Nusra," a Western intelligence official tells me with a grimace about a group under UN Security Council sanctions and on the US list of terrorist groups.

Russia and Egypt recently embarked on some still unconvincing efforts to relaunch a political process.

The UN's focus has been narrowed to a possible "freeze" in hostilities in one district in one divided city, Aleppo, and a temporary suspension of government bombardment across the city.

"It's a pilot project," the UN's third envoy in four years Staffan de Mistura told me recently. "We want people to see the benefits... and we have to start somewhere".

Rare bright spark

Under political fire from all sides, the veteran UN troubleshooter holds up his own reminder of the darkness that is now Syria - a tome of a book, with a pitch black cover, entitled #100,000Names. Pages and pages that list the dead cover less than half the number of Syrians who have lost their lives so far.

It's this sad catalogue of abuse that leads many Syrians to say they can never accept a role for President Assad and other leading members of his regime, in any future order.

But those who back him see in this book a story of an opposition backed by powerful Arab and Western states with their own agendas for Syria.

There was a rare bright spark this month when the UN's agency for Palestinian refugees was able to get agreement from all sides to resume distribution of food and medical supplies to besieged Yarmouk, just south of Damascus, after a hiatus of more than three months.

But like most of the world's work on Syria, it simply didn't cover the needs of so many people desperate for food, water, medical care, and most of all freedom.

And it's all too fragile, all too hostage to the vagaries of this war.

And like much of Syria, it's just one small bright light in a big dark hole.