Iran hardliners cling to death penalty

- Published

Narges Mohammadi and her children, Kiana and Ali

The jailing of a well-known campaigner against the death penalty and a sharp rise in executions has once again put Iran's poor human rights record in the spotlight.

Why has President Hassan Rouhani and his team failed to meet hopes for reform at home despite making gains on the international stage?

"They took my mummy to Evin prison again," says eight-year-old Kiana.

In their short lives, Kiana and her twin brother, Ali, have seen many arrests and raids on their home.

Their mother is Narges Mohammadi, a well-known human rights lawyer and campaigner, who has been in and out of jail on charges related to her work, for much of the past five years.

In 2012, after suffering severe ill-health, Ms Mohammadi was granted leave to serve the remainder of a six-year prison sentence at home.

But last week while the children were at school, intelligence officials came to the house, with no warning or explanation, and took her back to jail.

One of the charges levelled against Ms Mohammadi was that she was running an "illegal group" campaigning against the death penalty.

It is a tough cause to fight in a country that has the second highest rate of executions in the world, after China.

When President Rouhani swept to power in 2013, there were hopes his more moderate stance would mean improvements in human rights.

But since he took office, the number of executions carried out in Iran has actually risen.

President Rouhani is thought to be a moderate influence

The Oslo-based Iran Human Rights, external organisation says Iran executed 735 people in 2014 - a 10% increase on the previous year.

In April the group said it had documented 43 judicial killings in Iran in just three days.

It is impossible to independently verify these numbers, but most human right observers say they are credible.

The majority of executions carried out in Iran are for drugs-related offences And in a country with a serious addiction problem, they elicit little public sympathy.

But in the past two years, there have been a number of high-profile death row cases - mainly involving juvenile offenders or women - which have struck a chord with the public, prompting appeals for clemency.

But President Rouhani has so far kept silent about the death penalty.

The main reason is that constitutionally he has very little room to act.

Although he is the elected president, Iran's complex power structure means Mr Rouhani has no power over the judiciary, which answers instead to the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Internal suspicion

The judiciary is dominated by hardliners deeply suspicious of the overtures Mr Rouhani has been making to old adversaries such as the US.

The more ground the president gains on the international stage, the more resistance the hardliners will put up to any change to the status quo at home.

Executions in Iran:

In the 18 months since the election of President Rouhani in June 2013, Iranian authorities executed more than 1,193 people. This is an average of more than two executions every day.

The number of executions in that period was 31% higher than the number in the 18 months before President Rouhani assumed power.

The number of juvenile offenders executed in 2014 was the highest since 1990.

Source: Iran Human Rights (March 2015)

"There is an internal conflict going on now between the hard-line judiciary and Rouhani's moderate administration," says Iranian human rights campaigner Taghi Rahmani.

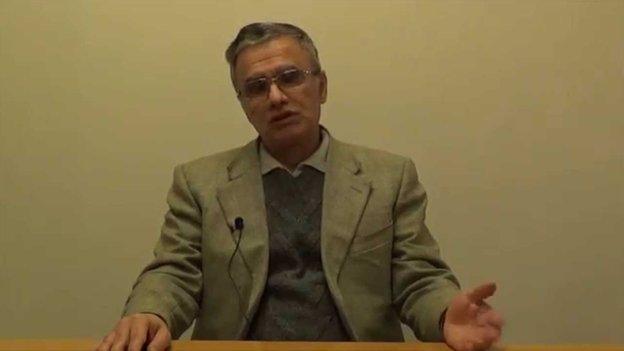

Taghi Rahmani says the authorities are trying to silence dissenting voices

"And it's the activists who are paying the price."

Mr Rahmani is married to Narges Mohammadi, and like his wife a veteran of the Iranian prison system. He has spent 14 years in jail for his political activities.

Ms Mohammadi is not the only campaigner to make the headlines.

In recent weeks, there has been outcry on Iranian opposition social-media sites over the judiciary's treatment of a number of well-known activists.

Ahmad Hashemi is a respected former government official in his 60s who was jailed for supporting the opposition protests in 2009.

In early May, he was allowed out of prison to visit his terminally ill wife only to discover that she had already died and he was in fact going to her funeral.

At the same time Majid Tavakoli, external, a charismatic student activist, was also given leave towards the end of a four-year prison sentence.

But after just three days at home with his mother, he was suddenly recalled to serve out the remaining two weeks of his sentence.

As Iran prepares to hold a general election in February 2016, the stand-off between moderates and hardliners is expected to intensify, and there are fears that this will lead to a further crackdown on opposition activists, journalists and campaigners.

Taghi Rahmani told the BBC his wife's detention was a warning shot.

"By arresting her, they are trying to send a signal to others to stay quiet," he said.

Narges Mohammadi had been released on the grounds of ill health

With international talks over Iran's nuclear programme now approaching a crucial June deadline, President Rouhani is focusing all his efforts on reaching a final agreement.

To clinch a deal, he needs the support of the country's supreme leader. And observers say this means that right now he has neither the time nor the will to address human rights reform or the death penalty.

Mr Rahmani says whatever happens, he and his wife are not planning to give up their political activities.

But it is clear they and their family are paying a heavy price.

Mr Rahmani now lives in self-imposed exile in France and has only seen his children once in the past three years.

With his wife back in jail, Kiana and Ali are now living with their grandmother.

"The one thing I really worry about," he told the BBC.

"Is that one day, my kids might question our decision to take a stand."