The challenge of assessing Syria's chemical weapons

- Published

For the past year, since the last declared material left the country, there have been reports that chemicals such as chlorine and ammonia continue to be used for attacks in Syria.

In April this year, members of the UN Security Council witnessed video and heard first-hand reports of one such attack, external, involving chlorine.

Chlorine is a common industrial chemical, but its use as a weapon is banned by the Chemical Weapons Convention.

There has also been an increasing number of statements expressing concern with the veracity of Syria's initial chemical weapons declaration, external. In early May, a leaked report acquired by Reuters indicated that evidence of chemical weapons material was found at an undeclared site, external.

So is the Syria declaration complete? Are chemical weapons still being used in Syria? And why is it so difficult to monitor what weapons they still have?

What has happened so far?

In 2013, Syria signed the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), external and agreed to the destruction of its chemical weapons. It approved the initiative after the nerve agent sarin was used in an attack on several suburbs of Damascus that killed hundreds of people. Western powers said it could only have been carried out by Syria's government. The regime and its ally Russia blamed opposition forces.

In June 2014, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) declared that the last of Syria's declared chemical weapons were shipped out of the country for destruction, but since then reports have persisted of chemical attacks.

A man inspects a site targeted by what activists said was a poison gas attack in the village of Sarmin in Idlib province in March 2015

The OPCW has sought to address this by setting up two teams:

The Declaration Assessment Team (DAT) was responsible for engaging with Syria's chemical weapons programme leaders to better understand and obtain clarification on issues within the declaration

The Fact Finding Mission (FFM) whose role was to determine whether chemical weapons were continuing to be used

The FFM's report in late 2014 stated that it had found information constituting "compelling confirmation" that a toxic chemical was used as a weapon "systematically and repeatedly" in a number of attacks on Syrian opposition-held villages.

The report also stated: "The descriptions, physical properties, behaviour of the gas, and signs and symptoms resulting from exposure, as well as the response of patients to the treatment, leads the FFM to conclude with a high degree of confidence that chlorine, either pure or in mixture, is the toxic chemical in question."

Why might Syria want to retain some of its chemical weapons?

There are a number of possible reasons including:

The desire to retain some sort of strategic capability. Whilst any retained quantity is now probably sub-strategic, if Syria were to hand over the material to Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shia militant group, it might have a strategic effect

Perhaps more likely is that some may be retained in the event of catastrophic regime collapse. The Alawites - the sect to which President Bashar al-Assad belongs and which dominates senior positions in the government and security services - and any allies may plan to consolidate in their traditional areas of north-west Syria as some form of mini, quasi-state. With little left to lose, chemical weapons may become the weapon of last resort

It may just be a very simple reason: old habits die hard. There may be no specific rational plan. The regime and the programme leaders just don't want to let go of a high-won, extremely expensive capability

What are the difficulties on the ground for inspectors?

OPCW inspections are based primarily on the member state's own declaration. Routine inspection missions occur to verify such information by visits to the declared facilities.

In the course of reviewing Syria's initial declaration, the OPCW encountered a number of issues, external on which it required further clarification, including Syria's production of ricin (a toxin banned under the CWC), the destruction of mustard agent prior to joining the CWC, and the conversion of unfilled chemical munitions into conventional, explosive ordnance.

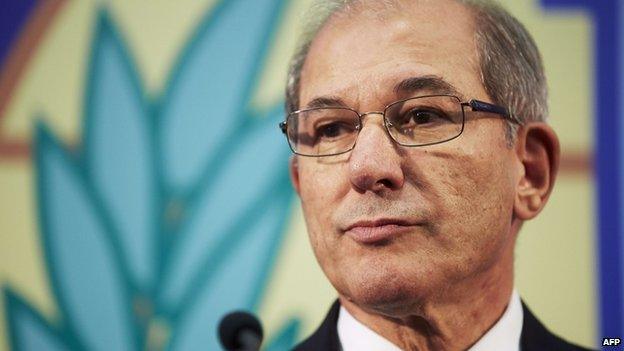

Ahmet Uzumcu, the head of the OPCW, admits that the Declaration Assessment Team's work is an informal process

The DAT work is an informal process, as OPCW director general Ahmet Uzumcu freely admits. It was reported in March 2015 that the team was on its eighth visit to Syria, external.

A more formal, but potentially more confrontational, approach would be for a member state to accuse Syria of hiding something. Article IX of the CWC, or a small paragraph tucked away in the UN Resolution and EC Decision allows this option.

An OPCW team could have the mandate to visit any site suspected of containing evidence of a breach to the Convention, a so-called "Challenge Inspection". Thus, rather than working from information supplied in Syria's own declaration, or as a result of the OPCW's own analysis, this mission would be based on a third party's intelligence information. This is likely to raise the tension significantly.

In theory, Syria is obliged to allow this team to go anywhere.

However, unlike the Saddam regime's relationship with UN Special Commission inspections two decades ago, the Syrian government holds all the cards. They have a range of options to impede an inspection team's activities.

They could stop movement to a specific location by simply stating that it too dangerous. If a team ignores this advice, there are a number of options to ensure they do not get to their destination. The ultimate sanction being a physical attack, deniable under the "fog" of the civil war.

What problems does the chemistry throw up?

What is so challenging about an investigation into a non-persistent toxic substance such as chlorine is the very character of the material.

As a volatile gas, chlorine does not hang around in nature. It is either dispersed to undetectable levels, or binds with other compounds and becomes part of the background. Distinguishing chlorine used as a weapon, either from environmental samples in soil, or from the blood or tissue of victims, is extremely difficult. The only real chance is if samples are taken within a very few hours of an attack.

The 2013 UN investigation led by Prof Ake Sellstrom focused primarily on the August attacks around Damascus. A key reason that his reports were so robust was the relatively short time between the events and the sampling and interviews - less than 100 hours.

Whilst sarin nerve agent is also considered to be "non-persistent", its molecular structure means that breakdown products and unique physiological markers remain detectable for a much longer period after use.

What standards must the evidence meet?

To maintain a credible process, particularly in such a politically charged arena, it is not sufficient just to conduct inspections in a scientifically sound manner. So the other key aspect of the Sellstrom mission was his team's robust system of acquiring and managing the evidence. As well as being scientifically rigorous, the investigation was completely impartial, and most importantly it was seen to be so.

Inspectors need a robust system for collecting evidence

Investigators into the alleged chlorine attacks might only really rely on witness interviews and secondary evidence such as videos. Whilst the evidence they acquire might be compelling, it will be challenging to use it for further purposes.

The precise standards of evidence vary around the world, but the common approach is that in criminal cases prosecutors need to demonstrate "beyond reasonable doubt", whereas civil cases require only a "balance of probability".

The question is whether the evidence in an investigation into these alleged uses is sufficient in either case. The nature of the current Syrian environment is a significant constraint on any investigation. Establishing and maintaining a proper evidence management system, with mutually supporting data, is difficult at the best of times. In this war the challenges increase exponentially.

Of course it is not impossible. The fact-finding team may be able to further establish some very strong circumstantial evidence.

To some extent this has already occurred: with the reporting that some of the chemical weapons were dropped from an aircraft, thereby implicating the government as the sole user of such military hardware.

But to prove the use of chlorine as a weapon, let alone determine the perpetrator, will be a huge challenge.

Jerry Smith is the former head of contingency operations at the OPCW. He was the deputy head of the OPCW-UN Joint Mission to Syria. He is now an independent security risk management consultant.