Middle East map carved up by caliphates, enclaves and fiefdoms

- Published

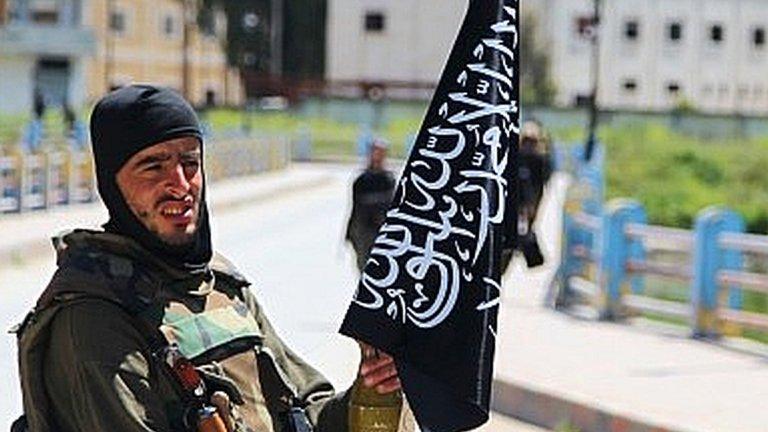

Islamic State has seized a swathe of territory across Syria and Iraq, which it calls a caliphate

Nearly a century after the Middle East's frontiers were established by British and French colonialists, the maps delineating the region's nation states are being overtaken by events.

Countries created to suit the imperial designs of London and Paris are being replaced by patches of territory carved out by jihadis, nationalists, rebels and warlords.

The border between Iraq and Syria is under the control of the so-called Islamic State; Syrian Kurds are experiencing the kind of autonomy their counterparts in Iraq have had for years; ethnic, tribal and religious leaders are running territories in Libya and Yemen.

As some of the nation states disintegrate, once powerful capital cities become ever more irrelevant. The rest of the world may have embassies in the Middle East but, increasingly, there are no effective ministries for them to interact with.

An alliance of Islamist militias controls large parts of Libya

The governments in Baghdad, Damascus, Tobruk and Sanaa are now unable to assert their will across large parts of their countries.

"The states that exist in the region do not really have a monopoly on the use of force," LSE Professor Fawaz Gerges told Newshour Extra.

That means that some central governments are now relying on militants and non-state actors to defend them.

Smuggling

Even the most precious Middle Eastern resource of all - oil - is slipping out of government control.

The Iraqi Kurds have been creating a legal infrastructure for oil exports for nearly a decade, while rebel forces in Libya and the Islamic State group have both accrued revenues from the oil industry.

While non-state actors find it difficult to sell crude oil, smuggling refined gasoline products is far easier.

"There is a network which crosses religious and ideological borders where you have people buying and selling petroleum, diesel and gasoline products across the whole region," says oil industry consultant John Hamilton. "And it's very profitable."

There are many explanations for the winds of change sweeping through the Middle East.

Depending on their point of view, analysts cite the failure of Arab nationalism; a lack of democratic development; post-colonialism; Zionism; Western trade protectionism; corruption; low education standards; and the global revival of radical Islamism.

But perhaps the most powerful immediate force ripping Middle Eastern societies apart is sectarianism. Throughout the region Sunni and Shia Muslims are engaged in violent conflict.

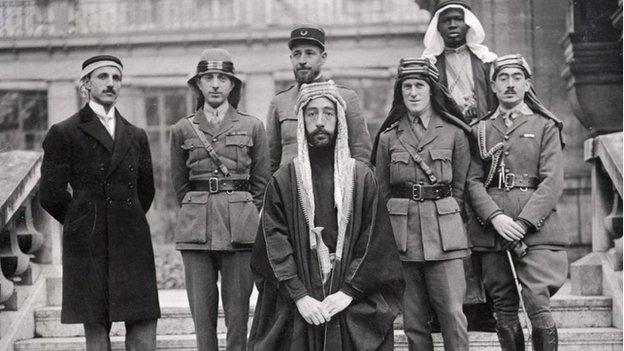

Britain and France drew the region's borders at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, attended by Prince Feisal (c) and TE Lawrence (middle row, 2nd from right)

The two regional superpowers, Saudi Arabia and Iran, both sponsor proxy forces to fight their battles for them.

In times past the global superpowers were able to keep the Middle Eastern nation states intact, but it's far from clear that either Washington or Moscow now have the power or the will to reunite countries such as Syria, Libya, Yemen and Iraq.

Looking further ahead, the question most Western diplomats are asking is not whether the old order can be rebuilt but whether still-intact countries such as Egypt, Jordan, Bahrain and even Saudi Arabia can hold the line.

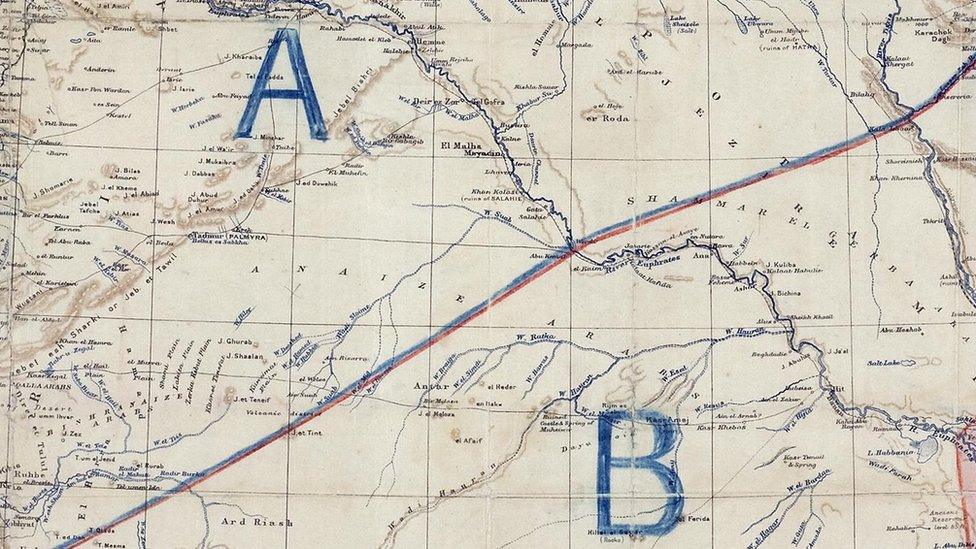

Most of the nation states in the Middle East were created in the aftermath of the First World War. The Sykes-Picot agreement and arrangements made by the League of Nations established the borders that exist today.

What was Sykes-Picot?

A secret understanding concluded in May 1916, during World War One, between Great Britain and France, with the assent of Russia, for the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire

The agreement led to the division of Turkish-held Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Palestine into various French and British-administered areas. The agreement took its name from its negotiators, Sir Mark Sykes of Britain and Georges Picot of France.

'Game-changer'

The biggest change since then came with the creation of Israel in 1948.

Israel's borders remain a matter of impassioned debate. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's new Deputy Foreign Minister, Tzipi Hotovely, recently told members of the Israeli diplomatic corps that they should tell the world that the West Bank belongs to the Jews.

The biggest shake-up to regional borders since WW1 came with the proclamation of the state of Israel in 1948

Some Palestinians also dream of border change - however it comes.

"They see the chaos in Iraq and Syria and this hideous machine called IS [Islamic State] as potentially the only game-changer that might ultimately call all the borders into question in a way that might eventually benefit the Palestinians," says Professor Rosemary Hollis of City University, London.

"Otherwise they see their future as miserable."

The Middle East is facing years of turmoil. Many in the region are increasingly driven by religion and ideology rather than nationalism.

For them - whether conservative or liberal, religious or secular - the priority is not to change lines on the map but to advance their view of how society should be organised.

For more on this story, listen to Newshour Extra on the BBC iPlayer or download the podcast.

- Published14 December 2013

- Published14 May 2015

- Published10 July 2015

- Published11 March 2016

- Published22 May 2015

- Published11 August 2014

- Published2 August 2014