What will Opec do about the oil supply?

- Published

Oil prices have fallen sharply

With oil prices down some 40% in a year, the oil ministers of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) are once again getting together in Vienna this week to decide whether to cut output or keep pumping crude oil into a market that is already oversupplied.

Six months ago, Opec's lack of consensus on a similar decision cost them almost $6 a barrel.

Some may argue that in a changing world, Opec is no longer as relevant to global oil markets, but Opec summits still command attention in both the industry and the global media and this week's meeting is no exception.

Opec has 12 member countries that between them sit on 80% of the world's oil reserves and produce four in every 10 barrels of oil.

The bloc is divided into two camps.

Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Qatar say Opec should keep current production levels, in order to maintain its market share, although that means low oil prices for all.

These so-called "price doves" can afford this policy thanks to their high per capita income and massive oil-generated sovereign wealth funds.

In Saudi Arabia's case, there is also the motivating factor of a growing domestic demand for energy.

"In a sense… it's no longer Opec's decision, it's Saudi Arabia's decision," says Paul Stevens, senior fellow for energy at the Royal Institute of Foreign Affairs.

"The reason they decided not to cut [last year] was because Saudi Arabia said they were not going to cut.

"If there is a decision in June, it will be effectively Saudi Arabia's decision."

Poorer camp

In the other camp are the poorer countries - Venezuela, Iraq, Iran, Algeria, Libya, Nigeria, Angola and Ecuador, who favour cutting production to boost prices and increase their revenues.

Most of the so-called "price hawks" struggle to balance the books when oil prices fall under $100 a barrel - a situation they've been grappling with for the past nine months.

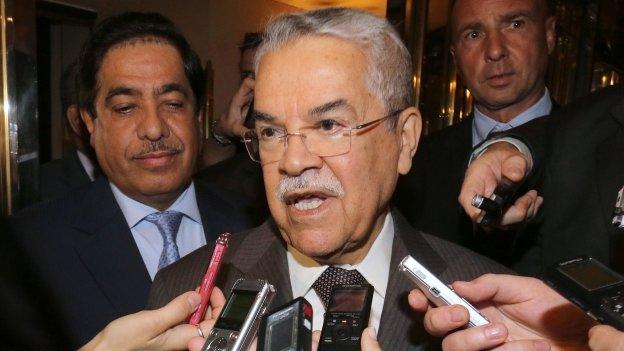

Saudi Arabia's Minister of Petroleum and Mineral Resources Ali Ibrahim Naimi will be a key voice

However, the views of one of the price hawks, Iran, are somewhat harder to predict.

Tehran has indicated it will increase productions levels if it succeeds in reaching a deal with world powers over its nuclear programme later this month, and international sanctions on its oil exports are lifted.

It's not clear at this stage how quickly this could happen.

With the US fast becoming energy independent due to new fracking technology, Opec is already pumping 2 million barrels of crude a day more than current demand.

Shale oil helps US producers churn out more than 12 million barrels a day, comfortably overtaking Saudi Arabia, once the world's largest producer, whose output was around 11 million barrels a day last year.

But shale oil is expensive to produce. The break-even price for a barrel has a range of $60-$70 depending on production location. By comparison, it costs less than $10 to produce a barrel of oil in most of the Gulf states.

Many analysts suspect that the Saudi strategy is to allow low prices to stay long enough to wipe US shale producers off the market.

Observers say American shale producers have now practically replaced Opec as the so-called "swing producer" of the oil market, cutting output when prices fall.

"When the price goes back up again or as it begins to go back up, you will suddenly see a lot of these wells coming on stream," says Paul Stevens.

"We're talking in terms of weeks and months rather than years. So their significance is that they effectively put a ceiling on the oil price."

Key difference

Yet, there is a key difference between how Opec used to balance the market and how shale producers behave.

This is because the US is not a major oil-producing Opec member like Iran or Saudi Arabia, says Iman Nasseri, from the FGE energy consultancy group.

"US producers are numerous. They are not governed by one oil minister who can decide on and dictate the level of shale production."

Opec:

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries was founded in Baghdad, Iraq, with the signing of an agreement in September 1960 by five countries: Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela.

They were joined by Qatar (1961), Indonesia (1962), Libya (1962), the United Arab Emirates (1967), Algeria (1969), Nigeria (1971), Ecuador (1973), Gabon (1975) and Angola (2007).

From December 1992 until October 2007, Ecuador suspended its membership. Gabon terminated its membership in 1995. Indonesia suspended its membership effective from January 2009.

Saudi Arabia is said to agree to a cut in Opec output only if the world's third largest producer, Russia follows suit.

The Saudis worry Russia may steal their market share, by replacing Opec oil.

Fracking has transformed the US energy market

Just as with mobile phone services, once you change provider there is seldom any going back.

Once an oil buyer has to adjust its refinery's settings to a new kind of crude, from a new supplier, they rarely bother changing again.

This year the main Opec ministerial meeting on Friday is preceded by a two-day seminar at Vienna's Hofburg Palace where non-Opec oil ministers will rub shoulders with top executives from the worlds's biggest energy companies.

Royal Dutch Shell, BP, Total, Chevron, Exxonmobil and even China's Sinopec are all on the guest list.

Opec ministers are expected to lobby heavily with their counterparts from Russia and other countries to come up with a co-ordinated response to the rise of the Americans.

But very few actually expect that this will happen.

US oil producers may be scattered and disparate, but so too are the Opec countries.