Viewpoint: Does strategy of killing militant leaders work?

- Published

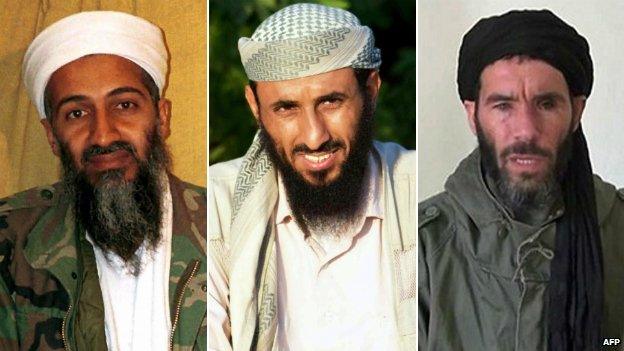

Osama Bin Laden (left), Nasser al-Wuhayshi (centre) and Mokhtar Belmokhtar (right)

The West's "whack-a-mole" approach to counter-terrorism has gathered momentum with the killing of Nasser al-Wuhayshi, leader of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

There are also rumours that Mokhtar Belmokhtar, the leader of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), has also been killed in a separate drone strike in Libya although the group has denied this.

Meanwhile, the United States deployed a special forces team deep inside Syrian territory last month which killed Abu Sayyaf, a senior figure within Islamic State.

Killing jihadist leaders is an established policy, although its efficacy as a strategy is not always clear. The most famous example of this approach, of course, came with the raid to kill Osama bin Laden in Pakistan.

A few months later the wildly popular al-Qaeda ideologue, Anwar al-Awlaki, was killed in a drone strike in Yemen. The appeal of both men declined sharply afterwards prompting the view that killing terrorist leaders might be enough to force the global jihad movement into terminal decline.

Killing ideology

That belief has pervaded parts of US President Barack Obama's administration, which has pursued an aggressive drone strategy aimed at decimating much of al-Qaeda's leadership. The overwhelming majority of its most important figureheads have now been killed in this way, severely impacting the group's operations.

For a moment it seemed as if the so-called "War on Terror" was won.

Al-Qaeda hit back. When the group announced Osama Bin Laden's death, it asked: "Are the Americans able to kill what Sheikh Osama lived and fought for, even with all their soldiers, intelligence, and agencies? Never! Never! Sheikh Osama did not build an organisation that would die with him, nor would end with him."

A similar message of defiance followed the death of Awlaki when the group declared: "America has killed Sheikh Anwar, but they can never kill his ideology."

President Obama has pursued an aggressive drone strategy against militants

Indeed, the global jihadist current has not ended with the death of Osama bin Laden. Instead it has spread into something much more potent, particularly in Syria and Iraq where fighters of the Islamic State (IS) group run rampant.

They are, ironically, the inheritors of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi's legacy - the former leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq who was himself killed by the US in 2006.

When Islamic State detached itself from the central leadership of al-Qaeda to pursue an even more aggressive policy in Syria and Iraq, it claimed to be following the true spirit of Bin Laden's vision.

They defied his successor, Ayman al-Zawahiri, who had ordered IS to confine its operations to Iraq while leaving Jabhat al-Nusra to fight as the official representatives of al-Qaeda in Syria.

Filling the vacuum

The dispute between al-Qaeda and Islamic State has now given way to fratricidal conflict between the two groups and demonstrates both the limits and unintended consequences of killing terrorist leaders.

Herein lies the dilemma. There is obvious utility in killing terrorist leaders. Their deaths offer huge psychological blows to the groups they lead and impairs their operational capacity.

But there are clear drawbacks too. The vacuum left by the absence of terrorist leaders can also fracture the movements they leave behind, spawning even more violent and nihilistic offshoots.

Shiraz Maher is a Senior Fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR), King's College London. Follow him @ShirazMaher, external

- Published16 June 2015

- Published15 June 2015

- Published4 May 2015

- Published16 June 2015