Why a luxury-shopping revolution is coming to Iran

- Published

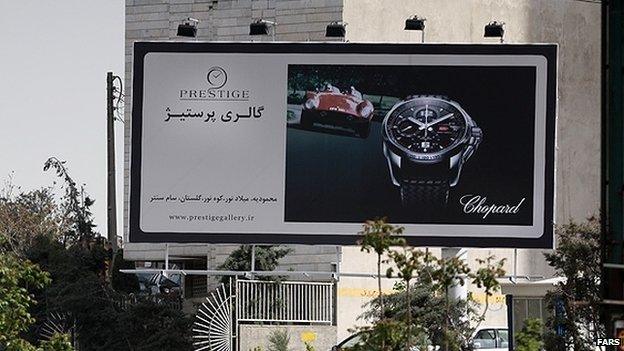

From the roadside billboards advertising Rolex and Louis Vuitton, to the glitzy shopping centres that have sprung up across Tehran, it's clear that big brands are becoming big business in Iran.

After decades of austerity following the Islamic Revolution, middle-class Iranians have developed a taste for high-end designer goods, and for Tehran's young rich, shopping has become the new religion.

"Exposure to foreign trends through travelling, the internet and satellite television has created a desire for branded products," says Bahar, a 30-year-old fashion blogger.

"Showing off is a big part of the story. By spending huge amounts of money on big brands, well-off Iranians want to show they've made it."

Living the high life

One group of super-rich young Tehranis have taken showing off to new levels with their own Instagram site - Rich Kids of Tehran, external, where without any perceptible sense of irony, they post pictures of their designer clothes and designer lifestyles.

When the site first appeared last year it prompted fury and resentment among poorer Iranians and the conservatives who dominate Iran's political and legal institutions.

But the Rich Kids seem undeterred by the controversy.

The Rich Kids of Tehran's Instagram feed features high-end vehicles

Recent postings include pictures of Tehran Fashion Week and a question about where people are going on holiday this year - the responses range from Italy and Istanbul to Japan and Dubai.

Because luxury brands are still the preserve of the rich, they don't yet show up in the Iranian Customs Authority's list of top 100 imports.

But there is an indication of the potential for growth in the most recent figures for cosmetics imports.

In the year to March 2015, cosmetics made up 0.1% of the country's $52bn (£32.8bn) total imports - many of them big name brands snapped up by increasingly image-conscious consumers.

Mall envy

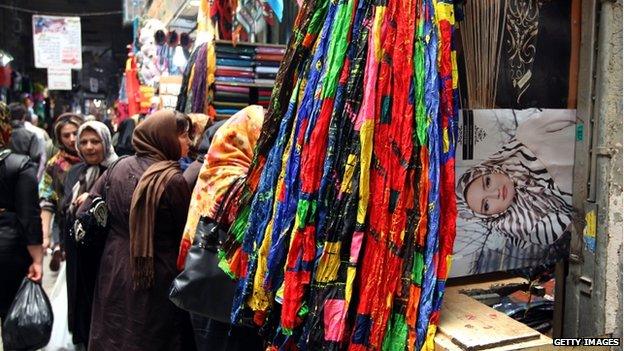

Iranians shop at the main old bazaar in Tehran

In big cities all across Iran, traditional bazaars now face fierce competition from American-style urban shopping centres where big name Western brands are on conspicuous display.

But although these luxury shopping centres look exactly the same as retail outlets anywhere in the world, the designer goods on display have actually been brought in by third-party importers via Turkey and the Gulf States.

The outlets that sell them have no connection to the big brand manufacturers.

Big Western fashion brands are not banned from doing business in Iran.

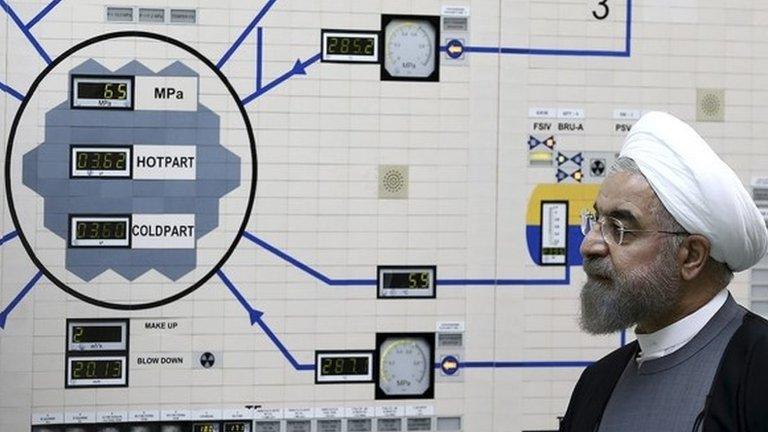

But international banking sanctions in place against Iran over its nuclear programme make it very difficult for them to get their profits out.

To date Spanish clothing retailer Mango, Italian fashion boutique Benetton, and luxury women's designer Escada, are among the very few Western companies to open shops in Iran.

Strict Islamic dress code in Iran also applies to advertising, so companies either have to show women fully covered, or just show the clothes on their own

The backdoor way in which foreign brands are imported into Iran means they are more expensive than they would be abroad, but so far this doesn't seem to be deterring the shoppers.

Mariam, an office worker who earns the equivalent of just $17,000 a year, has just blown more than a month's salary on a new Burberry bag.

She bought it online from an Iranian website that offers clothes and accessories from big brands and Western High Street retailers.

The site takes payments via local credit cards, and offers a free home-delivery service.

In the vanguard: Luxury retailers in Iran

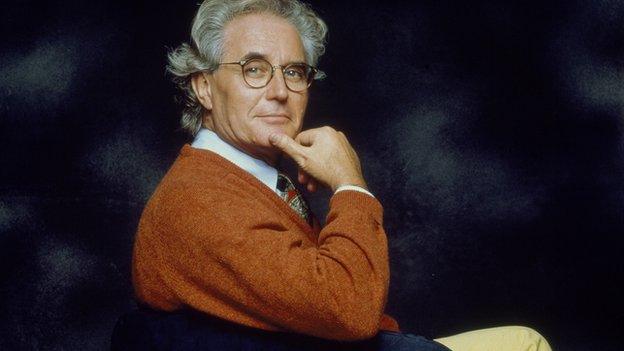

Luciano Benetton

Benetton was the brainchild of Italian Luciano Benetton, who launched the company back in 1963 with his sister and two brothers.

Benetton now has about 5,000 stores, employing more than 10,000 people.

Mango was founded in Barcelona, Spain, launched on the web in 2005, opening its first shop in 2000.

Mango now has 2,731 stores in 105 countries.

Escada was founded in 1978 by Margaretha and Wolfgang Ley in Munich, Germany.

Escada has shops in 80 countries worldwide.

Mariam told BBC Persian she would rather pay more for good-quality brand names than cheaper but inferior, locally made equivalents.

But she concedes that status also plays a big role in how she decides to spend her money.

"There's a lot of pressure on middle-class people to go out wearing designer clothes or an expensive watch," she says. "Personally I feel more confident when I'm wearing brands."

'Untapped market'

Fashion houses like Burberry currently have no control over this so-called "grey market" of their brand names in Iran.

But that is clearly something which could change.

Despite years of sanctions, the International Monetary Fund puts Iran's per capita GDP (gross domestic product) at $16,500.

That means Iranian consumers on average have more money to spend than their counterparts in emerging markets like Brazil, China, India and South Africa.

With the prospect of banking sanctions being lifted if a nuclear deal is finally reached, the big brands are waking up to the potential of a barely tapped market which could offer big dividends in the future.

- Published14 July 2015

- Published3 April 2015

- Published30 March 2015