Iran nuclear crisis: Six key points

- Published

Iran has agreed a long-term deal on its nuclear programme with six world powers, capping 12 years of on-off negotiations and potentially ending one of the world's most serious crises.

We're at a pivotal moment

The long-running dispute has widened divisions between Iran and the West, but a comprehensive accord might bring down diplomatic barriers.

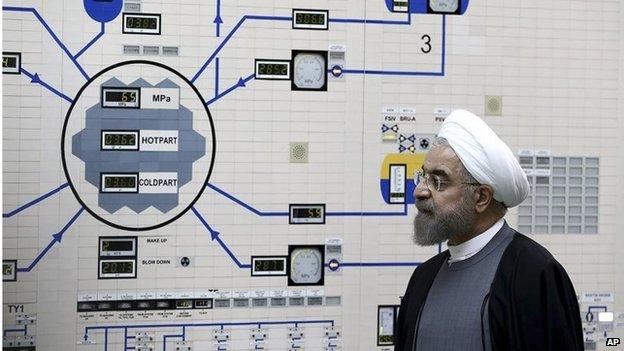

Multiple deadlines were missed as negotiators sought to build on an interim deal struck in November 2013 after the election of the moderate Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, who promised to end his country's international isolation.

US President Barack Obama said the agreement announced in Vienna marked "one more chapter in our pursuit of a safer, more helpful and more hopeful world".

Under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), external, Iran has agreed with the so-called P5+1 - the US, UK, France, Russia, China and Germany - to significantly limit its sensitive nuclear activities.

Iran will reduce its stockpile of enriched uranium - used to make reactor fuel, but also nuclear weapons - by 98% to 300kg (660lb) for 15 years. It will also cut by two-thirds to 5,060 the number of centrifuges installed to enrich uranium for a decade.

Sanctions imposed the UN, US and EU will be lifted as Iran's compliance is verified by the the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and more than $100bn (£64bn) in assets frozen overseas will be released. Should any aspect of the deal be violated, the sanctions will "snap back".

It's about fear and distrust

Years of distrust and suspicion have made the crisis over Iran's nuclear programme hard to solve.

The P5+1 want to be satisfied that Iran won't have the capacity to make a bomb in less than a year if it decided to - the so-called "break-out" time.

Iran for its part says it does not want a nuclear bomb, but insists on exercising its right to run a peaceful nuclear industry. It also wants crippling international sanctions lifted quickly.

Many countries do not believe Iran's declared intentions, and there is fear of what Iran might do with a nuclear weapon, and of the prospect of a nuclear arms race in one of the world's most unstable regions.

Lots of countries have nuclear weapons, but Iran's case is different

It looks to some like Iran has been singled out - after all, many countries have nuclear programmes and at least eight possess nuclear weapons. The reason why such attention has been focused on Iran is because it hid a clandestine uranium enrichment programme for 18 years, in breach of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, external (NPT).

As a result, the UN Security Council passed six resolutions, external requiring Iran to stop enriching uranium, a process that can ultimately produce the fissile material for a nuclear weapon.

Iran agreed to suspend parts of its nuclear programme under a temporary agreement in November 2013 in return for some sanctions relief, but this was a stop-gap deal, not an end to the crisis.

The international community was also worried about unanswered questions surrounding possible military dimensions to Iran's nuclear programme.

A 2007 US intelligence report, external said Iran had a nuclear weapons programme, but "halted" this in 2003.

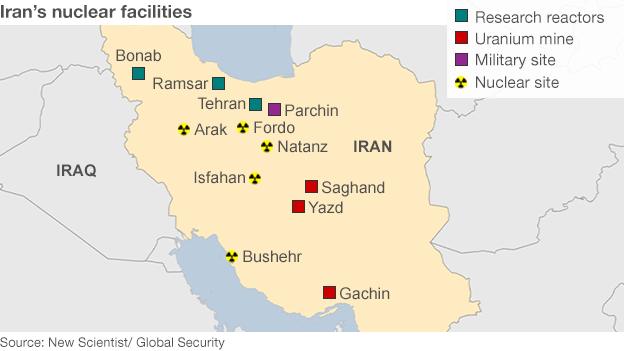

The global nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), has been investigating this in parallel to the main nuclear talks, but says Iran has not provided enough information about its past activities. These include possible nuclear-related tests at a secret military site, where Iran has barred IAEA inspectors.

Iran says the international community is displaying double standards by not doing anything about its arch-foe Israel, which is widely believed to have a nuclear arsenal - though Israel has neither confirmed nor denied this. Israel however, like nuclear-armed India and Pakistan, is not a signatory to the NPT.

Iran has been severely hit by sanctions

The BBC's Amir Paivar looks at the impact sanctions have had on Iran

Since Iran's undisclosed nuclear activities came to light, the country has been hit by a raft of sanctions - by the UN, EU, US and other countries.

These include a ban on the supply of heavy weaponry and nuclear-related technology to Iran, a block on arms exports, asset freezes, travel bans, bans on trade in precious metals, and bans on crude oil exports and banking transactions, among others.

The sanctions have contributed to a fall in the value of the Iranian riyal and to rising inflation, with the cost of basic foodstuffs and fuel soaring. This has hit ordinary Iranians, with some rare protests reported.

Under the 2013 interim deal, Iran got some sanctions relief in return for curbing its enrichment activities.

The comprehensive accord will see oil and financial sanctions phased out gradually as the IAEA confirms Iranian compliance. However, the UN weapons embargo and the ban on buying missile technology will remain in place for several years.

Some countries are unhappy about the deal

A deal which leaves Iran with any capacity whatsoever to build a bomb has alarmed Israel and Iran's neighbours in the Gulf.

Iran believes Israel should not exist. Israel sees a nuclear Iran as a major threat to it and the wider world.

Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said the comprehensive accord was a "bad mistake of historic proportions" that would allow Iran to "continue to pursue its aggression and terror in the region".

He has previously warned that Israel will do everything necessary to thwart the prospect of Iran developing nuclear weapons.

Saudi Arabia, the Sunni-ruled regional rival to Shia Iran, also fears a compromise deal will not stop Iran eventually getting a nuclear bomb. Saudi Arabia also worries that an end to sanctions will embolden and strengthen Iran economically and militarily.

Both Israel and Saudi Arabia, key US allies in the region, feel Washington is putting a deal with Iran before their security needs.

This is not the end of it

Although a deal has been agreed, it still does not mean the crisis is over.

While an agreement might defuse the stand-off between Iran and world powers, Israel and Saudi Arabia have warned it could fuel a nuclear arms race in the Middle East. Under this scenario, countries such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia could seek to equip themselves with nuclear weapons before Iran gets a chance to.

There are also strong opponents to a deal in both Iran and the US. In Iran, hardliners will portray the deal as a defeat for Iran, while in Washington members of Congress, where scepticism is strong, will have to approve the deal before US sanctions can be lifted.

US President Barack Obama himself has said he will support fresh sanctions against Iran if it does not uphold any agreement.