Iran nuclear agreement: A good deal, for now?

- Published

Both sides gave some ground to reach a deal - but critics say it does not go far enough

This deal could be historic. It is certainly controversial. Its opponents on Capitol Hill, in Iran, in Israel and the Gulf will continue to campaign against it. But it is practical proof once more that diplomacy is indeed the art of the possible.

One leading expert, Mark Fitzpatrick of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) in London, put it this way: "It's not a good deal, but it is an acceptable one."

There are still of course many questions about its implementation. Who has given more ground? Is the deal workable in the longer term?

But step back for a moment and think about where we were.

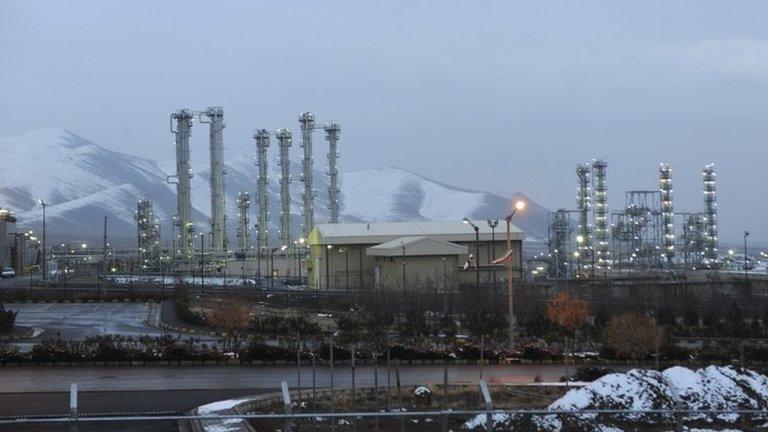

Before this negotiating process began in earnest - a process that resulted in the interim agreement in 2013, which in turn provided the platform for the talks that have just ended - Iran was advancing its nuclear programme at a steady rate.

Despite its claims that it did not seek a nuclear weapon, every day Tehran was moving closer towards the status of a "threshold state" - ie one standing at the very edge of having the capabilities and capacity to manufacture a bomb.

Indeed the "break-out time" - the period it would need to dash for a bomb before the wider international community could respond - was becoming ever shorter.

Sanctions were hurting, but not stopping its nuclear progress.

Israel, but more significantly the United States, were both talking about possible military action to try to stop Iran's nuclear programme in its tracks; a step fraught with military uncertainty that threatened to sow further regional chaos.

So if this deal is implemented successfully, conflict will have been averted and Iran's nuclear progress significantly curtailed.

Mutual concessions

The Americans and their allies have inevitably had to give ground.

Initially they wanted a total roll-back of Iran's nuclear programme and a halt to all uranium enrichment. That is indeed what Israel would still prefer.

But this was simply not practical if a deal was to be reached.

Under the agreement, Iran will scale down its nuclear infrastructure for up to 15 years

Indeed the agreements reached with Iran have implicitly underscored what it has always asserted, that it has a legal right to an enrichment programme.

The other essential requirement for a deal to be reached was the need for a "sunset clause" - in other words, a time limit after which restrictions on Iran's nuclear programme and research would be lifted.

Again, some hardliners in the West would have preferred these restrictions to last indefinitely - another non-starter that would have torpedoed any agreement.

But with a time-limited agreement - even one that extends out 10 to 15 years - there will be all sorts of questions about what happens then.

Iran will be able to resume its nuclear research with a much stronger economy to support it. Critics will view this with alarm.

But supporters of the deal will argue that the inspection regime is rigorous enough to give confidence about what Tehran is doing. And by then - perhaps - the wider relationship between Iran and many of its neighbours and the West will have improved.

Iran too has given ground. It is accepting a level of inspection greater than that directed against any country, other than those defeated in a war. It is accepting time-limited constraints on its nuclear activity and research for a significant period.

Hard work ahead

What will be crucial now will be implementing the deal, once the US Congress and the Iranian parliament have had their say. This is a process rather than a single action.

There are many aspects of this complex agreement which could pose problems.

Iran has to take various steps to consolidate and extend the restrictions it has already accepted on its nuclear programme which will trigger key elements of sanctions relief.

Will this process run smoothly? Iran clearly has no interest in throwing a spanner in the works at this stage.

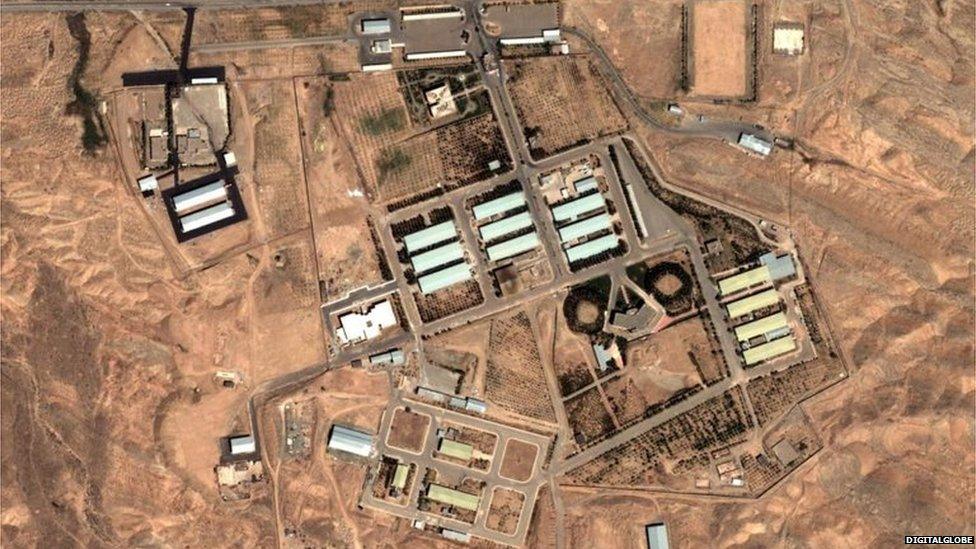

It remains to be seen if inspectors will be allowed unfettered access to sites which Iran has said are out of bounds

How will the inspection and verification regime work in practice? Will the so-called "managed access" for international inspectors to military sites for example be sufficient?

But suppose things do go wrong and there are Iranian activities that raise suspicions. How easy might it be to re-impose certain sanctions? Will some simply "snap back" into place, in the terms used by some of the negotiators?

And what might be the impact on this aspect of the agreement given the growing strains between Russia and the West?

The international community also needs to have a better understanding of Iran's past nuclear activities, especially those with "a possible military dimension".

The global nuclear body, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), has signed a so-called roadmap to clear up this long-standing dossier by the end of 2015.

Critics will note that Iran has made similar commitments in the past only to fail to honour them.

Crisis postponed?

Advocates of the deal will argue that while past knowledge is important, it is what happens going forward that matters most.

Arms control experts believe that there is enough in this deal to make it useful as far as it goes. Critics might at best say that the agreement simply "kicks the can down the road" so to speak - leaving the future of Iran's nuclear programme uncertain and postponing any crisis for some 10 to 15 years.

Given the state of the Middle East, that postponement might seem like a good deal for now.

This agreement narrowly relates to Iran's nuclear programme. But the Iranian regime will not change overnight.

Its foreign policy entanglements in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon and Gaza - many of which are seen as unhelpful by the West - will continue.

Many wonder if in the wake of this deal there should be further talks on the wider security problems of the region in which Iran is now such a central player.

- Published14 July 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published14 July 2015