Paranoia deepens wedge between Israelis and Palestinians

- Published

Fears of being attacked, or being mistaken for an attacker, have people on edge

We think of Jerusalem as a divided city and so it is - its Israeli and Palestinian populations are separated by language, religion, culture, politics and history.

And of course they have different political aspirations and territorial ambitions for the Holy City too.

But at times of rising tensions and rising casualty figures like this, the two populations that normally lead parallel lives share something very profound in common.

They are united by their fears for the dangers their families might face and by the deep urge that's within all of us to keep our children safe.

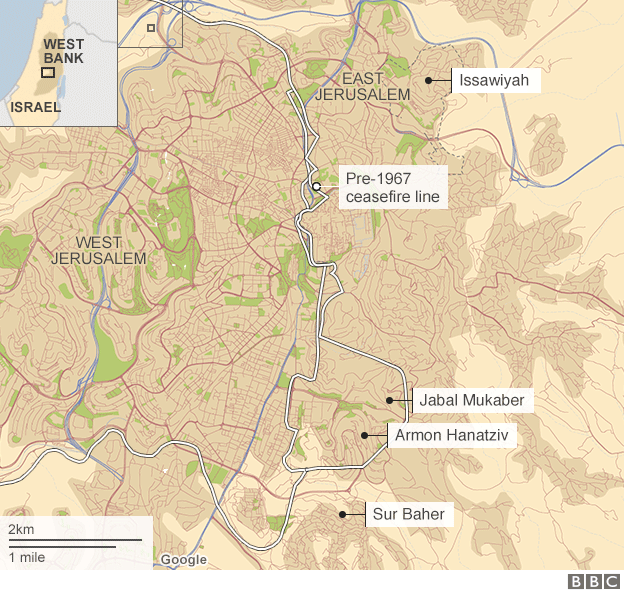

I met Dovi and Naama Singel, a young married couple with four children, in their apartment in the East Jerusalem Jewish settlement of Armon Hanatziv, on land occupied by Israeli forces during the 1967 war, where from the high ground you can see the nearby mosques and minarets of the neighbouring Palestinian districts of Jabal Mukaber and Sur Baher.

The areas are much closer together than outsiders to the city might realise and their residents see each other daily in banks or parks or shopping malls.

Dovi and Naama, parents of four children, now worry for their young family's safety

The Singels believe in - and work for - better relationships between the two communities but Dovi acknowledges these are frightening times.

"The biggest issue that I deal with every moment of every day," he told me, "is my fear for my children.

"We have four kids - even if I only had two of them, [what would be] the likelihood that I would be able to defend them? It almost cripples me because there really is nothing that I would necessarily be able to do."

Dovi has friends who are applying for firearms licences for the first time and for the first time in his life he is thinking about getting one himself.

He said: " I really don't want to have a gun in my house and that's why I haven't done it yet but I'm on the cusp of feeling like I don't have a choice other than to have some kind of weapon in my house."

'What are they thinking?'

Issawiyah sits on the eastern edge of the Jerusalem municipality - a Palestinian village captured like many others in the 1967 war and under Israeli occupation ever since.

Even in better times there is deep resentment in Issawiyah at the practical outworking of the occupation - Palestinians in villages like this pay the same local taxes as Israelis in West Jerusalem but strongly feel they don't receive the same services.

They point to the condition of the roads and pavements and the absence of recreational facilities.

"There are Jewish districts where they have parks for their dogs," one man told me, "And here we don't even have a park for our kids."

Bassem Obeid: Israelis look at me and wonder if I'm going to attack them

But in times of tension like this, sharper issues are suddenly thrown into focus.

There is an Israeli checkpoint at the main entrance to the village. The local people say that if anyone throws stones at the soldiers who man it, they close the road and force commuters returning from Jerusalem to wait in their cars for anything up to an hour.

And there is that change in atmosphere that everyone is talking about.

Bassem Obeid is a chef who works in a mixed environment in a hotel over in West Jerusalem - Jews and Palestinians rubbing shoulders in a shared economic space.

Bassem speaks fluent Hebrew - as many Palestinians do for practical, economic reasons - and says those working relationships are strong. But he knows that in general terms some Israelis have begun to see all Palestinians as potential attackers.

"When it shows that you're an Arab or they can recognise your language they look at you right away. It's like: 'There could be a danger coming from that direction' and it's not a very nice feeling.

"I like to look at people and have them look at me in the same way I look at them. I don't want to look at a person and see in his eyes that he's thinking: 'That could be a terrorist any minute.'"

'How do I hold my baby?'

Fear for the safety of children does unite the two communities, although the fears are different.

Israelis worry their children might be the victims of a politically-motivated street attack - Palestinians fear the readiness with which Israeli police and soldiers resort to lethal force, especially if they live in a part of the West Bank where it is easy to get caught up in street protests.

But in the end the way in which people experience that fear is deeply personal.

For Naama Singel, back in the district of Armon Hanatziv, it is the horror of the prospect of being attacked while out on her own with her four-month-old baby and the difficulty of knowing what to do if that happened.

Israelis have started arming themselves with forms of personal protection, from pepper spray to guns

"I took a self-defence class," she explained, "And one of the questions I asked was: 'I have a baby. When I walk with him, should he be in the stroller strapped in in case of attack and then I can just throw the stroller aside.'

"'Or should he be on me - that way I can run quickly, but then that cripples me in other ways and he's on me and most of the attacks are bodily attacks.' And they didn't really have an answer."

That is a good example of how the fears and anxieties triggered in this latest round of violence here are individual and deeply personal just as the attacks appear to have been spontaneous.

The US Secretary of State John Kerry has now embarked on a series of meetings with leaders on both sides in an attempt to reduce tensions.

But the random nature of the violence and its lack of an apparent link to any known organisation is going to make any kind of diplomatic or political intervention here even harder than usual.