A gulf between them: Understanding the Saudi-Iran dispute

- Published

Could open conflict now be one step closer between the two big regional powers in the Gulf? This week has seen tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran rise to dangerous levels following the Saudis' execution of a Shia cleric and the subsequent storming of the Saudi embassy in Tehran by an angry mob.

The BBC's Frank Gardner, whose attempted murderer was also executed by the Saudis last weekend, examines the historic enmity between the two regimes and assesses whether they can ever settle their differences.

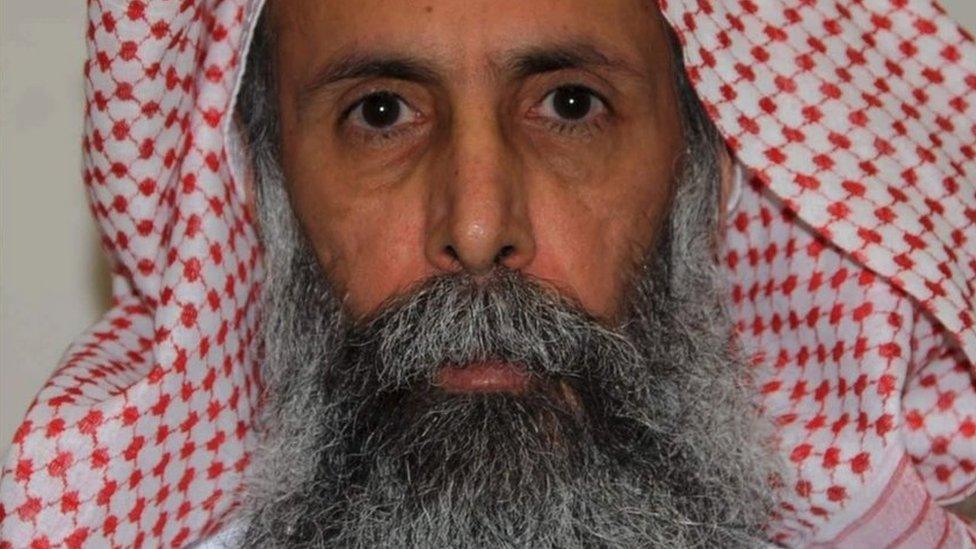

In Saudi Arabia, a country that last year put to death a record 153 convicted prisoners, there has rarely been a more controversial execution in recent years. Amongst the 47 condemned men whose sentences were carried out simultaneously on 2 January one name stood out from all the others.

Sheikh Nimr Al-Nimr, a firebrand Shia cleric and popular figurehead for thousands of disaffected Saudi Shias living in the country's Eastern Province.

Arrested in 2012 in the wake of the Arab Spring uprisings and charged with "disobedience to the ruler" and bearing arms, Al-Nimr's supporters insisted he only ever called for peaceful protest and fair rights for the Shia minority. His critics, including Sunni hardliners, called him a terrorist, while the Saudi government suspected him of being an agent of Iran.

Of the 47 people executed that day, 43 were Sunnis and most of those were extremists. One was the last surviving criminal from a gang that attacked our BBC film crew in Riyadh in 2004, killing my Irish cameraman Simon Cumbers and putting six bullets into me and crippling me for life.

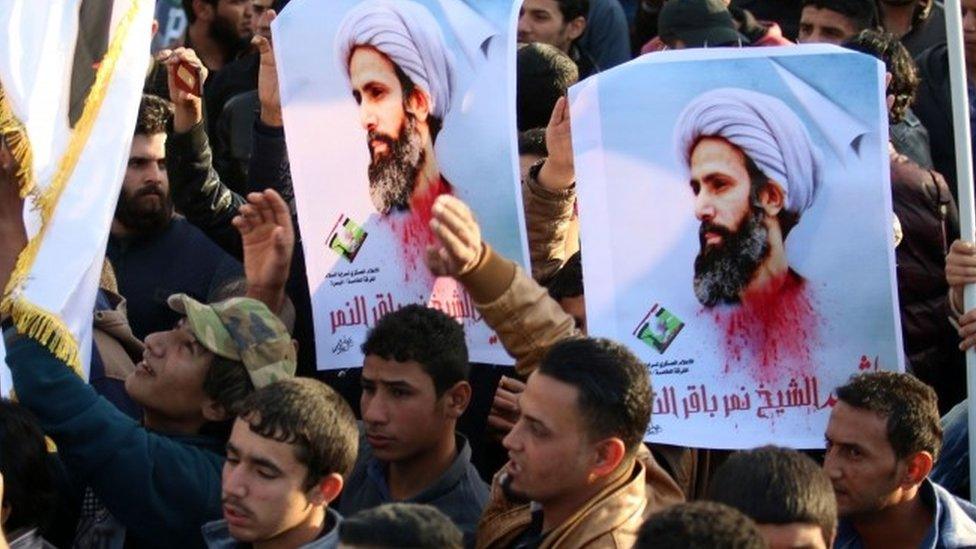

Yet it was the death of the Shia cleric Al-Nimr that was always going to be the most inflammatory in a region already beset with sectarian fault lines. There have been angry protests by Shia in Bahrain, Iraq and Lebanon.

More on Saudi-Iran tensions

The Saudi-US-Iran triangle: How crisis reflects deeply fractured Middle East

Great rivalry explained: Why don't Iran and Saudi Arabia get along?

Spiralling tensions: Why crisis is "most dangerous for decades"

Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr: Who was leading Saudi Shia cleric?

In Iran, a country ruled since 1979 by Shia clerics, and which reportedly executed nearly 1,000 of its own people last year, the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei said the Saudi leadership would face "divine revenge".

Optimists hoped that was a subtle way of absolving Iran from having to take any action itself.

But within a day an Iranian mob had vented its fury on the Saudi embassy in Tehran, setting it on fire and prompting Riyadh to sever all diplomatic, trade and transport links with Iran. For the hardliners in the Iranian regime, wary of their country's coming return to the world stage, this was probably a relief.

But for moderates and pragmatists keen to see last year's nuclear deal ratified and billions of dollars unfrozen, the embassy storming was an embarrassment they could have done without. One by one, Riyadh's allies - Bahrain, Sudan, Kuwait, Qatar and the UAE - have taken their own punitive measures against Iran. Saudi-Iranian relations are close to their lowest ebb for 30 years.

Power play

So where did this Saudi-Iranian hostility spring from and is it all about religion?

As a nation, Saudi Arabia has only been in existence since 1932 but the land it governs - most of the Arabian Peninsula - is the birthplace of Islam and home to its two holiest shrines, in Mecca and Medina.

In the early years of the Islamic conquests in the 7th Century AD Muslim armies burst out of Arabia to defeat the Persians, ending their Sasanian Empire. Later on in that century, following the death of the Prophet Muhammad, a dispute erupted over who should succeed as "khalifa", or caliph, to rule the burgeoning Islamic empire.

A breakaway group believed it should have been Ali, the Prophet's cousin and son-in-law, who was assassinated and his two sons denied the succession. The group became known as "Shia Ali", the party of Ali, and Shias still harbour this historic grudge. Today they are in a majority in Iran, Iraq, and Bahrain.

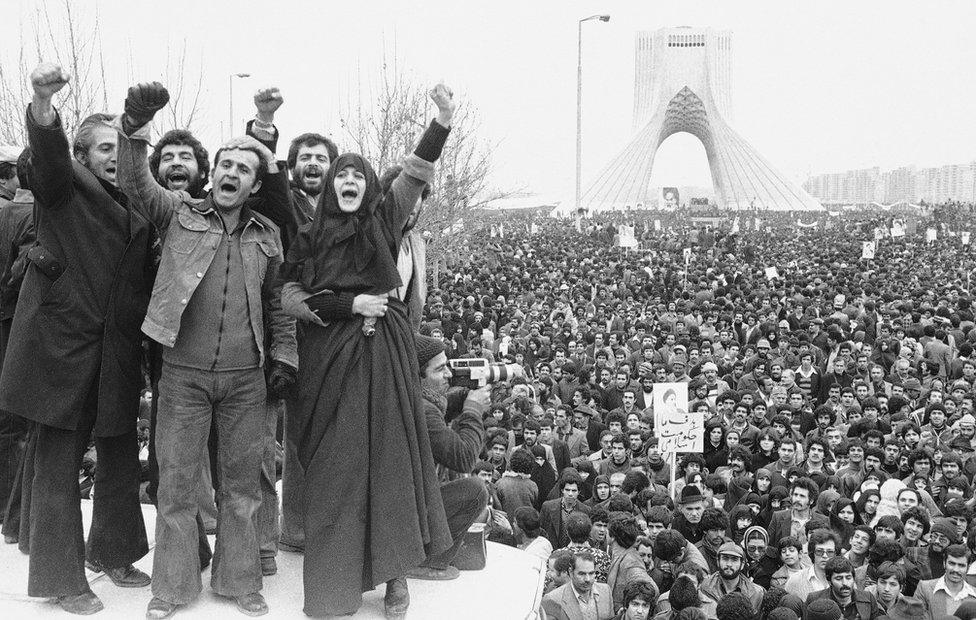

The 1979 Iranian revolution changed the dynamic in the Gulf

But in more recent times, the Saudi-Iranian rivalry has been primarily about power play, sparked by Iran's Islamic Revolution in 1979.

Before then, while the Shah of Iran was on the throne, relations were cordial and the Arab Gulf states were content to let Iran's navy act as "the policeman of the Gulf". Western expatriates living in either Iran or Saudi Arabia enjoyed a relatively relaxed, liberal lifestyle with frequent alcohol-fuelled parties in both affluent north Tehran and in the housing compounds of Dhahran.

That all changed with the Iranian revolution. Suddenly, a competition emerged to prove which country was most worthy of leading the Islamic world. As Iran's new rulers vowed to export their Islamic Revolution and undermine what they saw as corrupt, unworthy princes, Saudi Arabia outdid itself to crack down on anything deemed to be un-Islamic.

The final straw was the brief storming and occupation of the Grand Mosque in Mecca by a dissident Islamic group. The Al-Saud regime was shaken to the core and decided its key to survival was to cement its ties with the austere Wahhabi religious establishment, giving the clerics a huge say in areas of public life like education, justice and social mores.

Tension spikes

In practice this has led to a sort of quasi-arms race for influence, with both Iran and Saudi Arabia exporting and promoting their own versions of Islam, in direct competition with each other.

Syria's President Assad (R), seen here talking to Ali Akbar Velayati, a top adviser to Iran's Supreme Leader, is one of Tehran's allies

Iran's allies now include Hezbollah in Lebanon, Syria's President Assad, and the powerful Shia militias in Iraq, such as Asa'ib Ahl Al-Haqq, the same group that kidnapped five Britons in Baghdad in 2007 and murdered four of them.

The Saudis believe that what they call Iran's "meddling" in the region extends to other countries too, giving them a degree of paranoia. They accuse Iran of fuelling Shia discontent in Saudi and Bahrain and of backing the Houthi rebels in Yemen.

Iran's rulers for their part accuse the Saudis of bankrolling such an extreme, intolerant brand of Sunni Islam that they hold them responsible for the rise of jihadist groups like al-Qaeda and the so-called Islamic State (IS).

The current war of words between Riyadh and Tehran is only the latest in a succession of spikes in tension.

For eight years, as Iran and Iraq fought each other to a standstill in what locals called "the First Gulf War" from 1980-88, Saudi Arabia and its Arab Gulf allies backed Saddam Hussein's Iraq as a bulwark against revolutionary Iran.

In 1987 over 400 people were killed in Mecca when Iranian pilgrims held a political rally and clashed with Saudi security forces, leading to a three-year break in diplomatic ties.

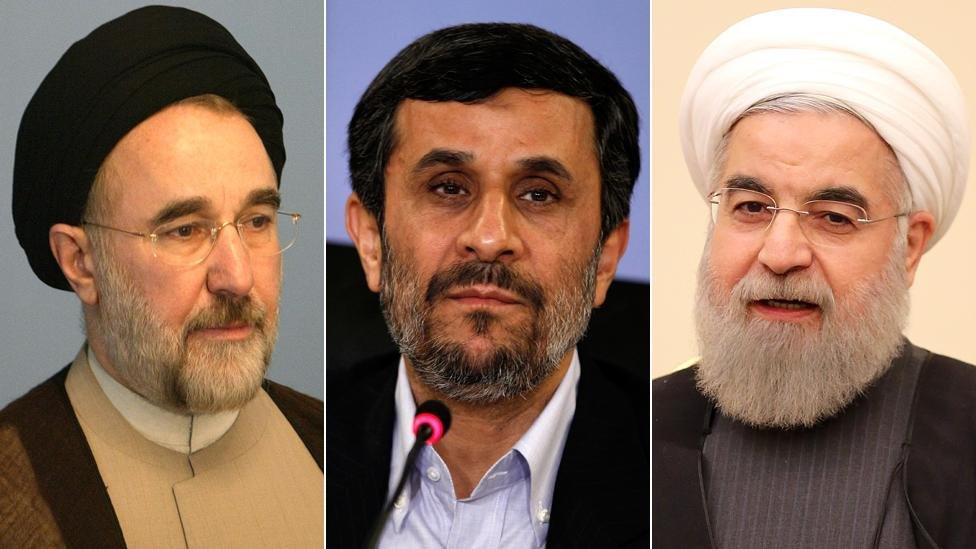

Khatami to Ahmadinejad to Rouhani

When Iran's moderate President Khatami came to power in 1997, better relations followed.

Soon after he was elected I sat with Iranian friends in a cafe in Shiraz. "You see those guys over there?" they said, pointing to a group of well-built, thuggish-looking men with scruffy beards and military jackets, sipping sweet tea and scowling. "They're the old guard, die-hard revolutionaries who hate the West and its allies. Their time is over."

The moderate President Khatami (L) was replaced by the populist hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (C), himself succeeded by the pragmatic Hassan Rouhani (R)

How wrong they were. In 2005 Khatami was succeeded by the combative President Ahmadinejad and relations with the Gulf Arabs took a nosedive as his mentors, the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps, were once more in the ascendant.

When the Arab Spring protests erupted in 2011, Iran, which had crushed its own democratic protest movement two years earlier, claimed the credit for sparking reformist movements across the Arab world.

This only deepened the Saudis' distrust of Tehran and in March that year, as Shia-led protests erupted in Bahrain, the Saudis sent 1,000 National Guard troops into Bahrain to guard key installations. It was a largely symbolic gesture, aimed at warning Tehran to back off and forget any idea of toppling the island's Sunni monarchy and replacing it with a Shia Islamic republic.

Today, Iran once again has a relatively moderate, pragmatic president in the form of Hassan Rouhani, while Saudi Arabia has embarked on a new and aggressive foreign policy that has seen it bogged down in an unwinnable war in Yemen.

Yet only two weeks ago there was talk of Saudi Arabia and Iran burying their differences around the table at the Syria peace talks. Perhaps a grand bargain could be struck that would finally end that country's appalling civil war. IS could be defeated as a common foe and Saudi Arabia and Iran could both end their military support for opposing sides.

Today those goals, while not impossible, have definitely receded over the horizon.

- Published5 January 2016

- Published4 January 2016

- Published4 January 2016

- Published2 January 2016

- Published4 January 2016