Syria conflict: What hope for Geneva peace talks?

- Published

The talks have already been delayed, amid arguments over who should attend

Making peace is always most difficult when no side in a war is winning - or losing - decisively. The combatants ask themselves: do we really gain enough by stopping now? Won't peace leave our enemies undefeated?

Despite all the bombing - even more intense since Russia started massive aerial attacks in support of President Bashar al-Assad last September - the battles for Syrian territory ebb and flow with no-one scoring a knockout blow.

Recently, Syrian government forces have claimed significant advances, including in the province of Latakia.

But there are a large number of different forces ranged against them: a huge range of rebel fighters more or less backed by Western and some Arab powers, and then there are the outlawed extremists, including the so-called Islamic State (IS). All that makes the search for negotiated peace even harder.

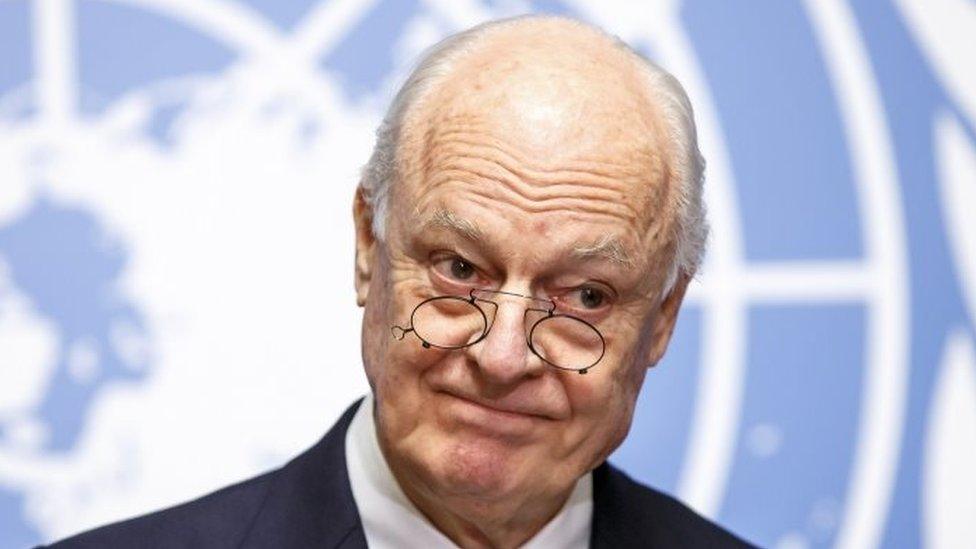

UN envoy Staffan de Mistura has been tight-lipped on who he has invited to join the talks

The pressure for progress is led by the governments of Europe, in particular.

They face two sets of challenges.

The first is to find a proper and adequate set of responses to the mass migration, led by Syrian refugees, which has created an unprecedented political crisis in Europe.

The crisis has multiplied deep divisions between European Union member states and exposed a profound lack of European unity. As long as the war in Syria continues, and the emptying out of the country goes on, the greater the number of people suffering in a man-made disaster.

The second challenge is from the spread of terror attacks and plots which can be traced back to the success of Islamists in seizing ungoverned spaces in Syria, as well as in Iraq and Libya.

Deep divisions

Millions of people have had to flee their homes since the conflict began in 2011

So, who will be at the Geneva peace talks? Well, the Syrian government were the first to put together a team and commit to attending - on their terms, of course.

Their overwhelming aim is as clear as it has ever been: regime survival.

There may be internal tensions within the regime about the medium- to long-term future for President Assad, but for now their proposition remains brutally simple: It's us or our opponents - and Damascus tries to brand all of them - not just the Islamist extremists - as terrorists.

The government side must be taking considerable comfort from the fact that Russia has thrown so much firepower behind them, and that the key Western powers, particularly the United States, place a higher priority on defeating IS than on active support for the rebel forces regarded by those powers as "moderate".

The opposition fighters, and their international backers, appear very divided.

The intense wrangling over who should, and should not, be entitled to represent the opposition has been a major factor delaying, even threatening, the Geneva talks.

The effect of those disagreements changes by the hour, but the coyness of UN talks convenor, Staffan de Mistura, initially refusing to say who he had invited to join the talks, speaks volumes about his recognition of the fragility of this entire process.

Tough path

The front lines in Syria are constantly shifting

When Turkey insists some Kurdish representatives be excluded from the talks, although Kurdish fighters have been the most successful against the Islamists, and when Saudi Arabia wants only its nominated list of opposition organisations allowed to attend the talks, those are further signs of the immense difficulties ahead.

Face-to-face talks between the warring parties in Geneva remain a distant prospect. The early stages will, at most, only be so-called "proximity talks".

The task of finding a way to move to a ceasefire in Syria, then a political settlement, and eventual peace, looks even harder than in previous peace talks. They collapsed in failure.