Syria: A different country after five years of war

- Published

The BBC's chief international correspondent Lyse Doucet was in Deraa five years ago and has returned to see what civil war has done to the country and its people.

Its first moments were fleeting and furtive, small but significant.

Young women unfurled protest banners from their handbags on a busy Damascus street, then quickly retreated. Teenage boys sprayed graffiti on a school wall in the southern city of Deraa.

Five years on, Syria's uprising is now the longest, most vicious conflict in what was first poetically depicted as the Arab Spring.

Many young activists, who first raised their heads and voices to call for political reform are now disenchanted, detained, displaced or dead.

Their cries have long since been drowned out by the deafening roar of a destructive war which sets a multiplying array of opposition forces against the Syrian army and its militias.

On both sides, there's the most bewildering array of outside actors ever seen in any war, anywhere. And then there's the so-called Islamic State (IS).

Syria's war is now everyone's war.

Rebel groups have gained control of some Damascus suburbs

'All people are afraid'

Syria, before this war, was a middle-income Arab state of exceptional hospitality, exquisite cuisine, fabled charm - and infamous repression.

It was a place in the 1990s where, in the wake of the Soviet Union's jarring collapse, I was constantly told "revolution is not for us, we prefer Syria to evolve". A former government official recently admitted to me it meant "change so slow, it was glacial".

Over the past five years of reporting on a extraordinary country's astonishing turn, many small moments told a much bigger story.

In 2011 among crowds milling around a mosque after Friday prayers, a young man nervously thrust a crumpled message into a colleague's hand. It read: "Thank you. But no one can meet with you because the army is in the street. All people are afraid."

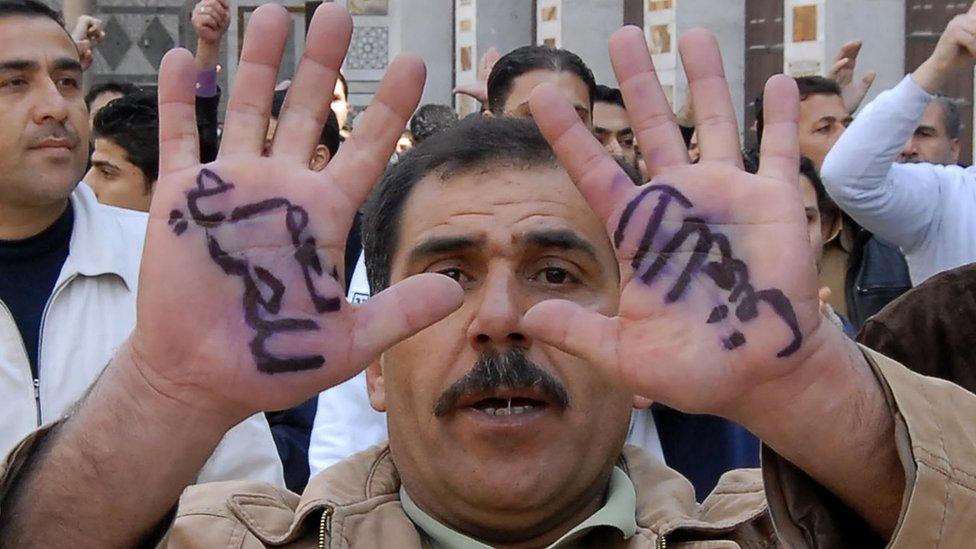

'No to violence, yes to freedom' - the message of anti-government protests in March 2011

"Look down the road," another man whispered tersely in my ear, as intelligence attired in track suits slipped through an anxious crowd in the Damascus neighbourhood of Barzeh. Down the road, soldiers stood in wait and snipers were in sight.

Six months later, a people too afraid to even to say they were afraid had lost their fear. Down that same road, residents beckoned us inside a warren of winding lanes filled with chants of protestors. Deep inside, a house belonging to the Free Syrian Army was peppered with shrapnel, blackened by fire.

Another six months on, that road was sealed off and silent. The army was back in charge.

Funerals and massacres

As the years dragged on, the momentum of battle shifted between sides.

Everyone paid a price.

In 2012, in the hilly heartland of President Assad's Alawite community in Latakia, entire villages turned out virtually every day, sometimes three times a day, to bury young soldiers returning in coffins from front lines.

My colleague Phil Goodwin, who filmed our reports on most trips, asked a man lingering by a graveside how such a warm people could have descended into such darkness. "There's a wild beast within all of us," he sighed.

Lyse Doucet: "A war crime happened here". This video contains graphic images

The worst in Syria has been the worst no one could have imagined.

In 2013 in the village of Haswiya, where news spread of a massacre, we opened a door on a sprawling compound to find houses of horror.

Charred bodies sprawled inside rooms and slumped across doorways, left where they'd been shot and burned. Washing hung on the clothes line and food was still in the oven.

Soldiers who escorted us blamed fighters of the al-Nusra Front. A villager whispered that members of a pro-government militia "had acted without orders".

In Syria's war, truth has been as hard to find as peace.

At times, there was a massacre almost every week. In every instance, someone lives with the knowledge of what really happened. Someday, there will be a reckoning.

Every weapon has been deployed, no one spared: neighbourhoods wiped out, chemical weapons unleashed, even children tortured.

Civilian areas in rebel-held cities and suburbs have been bombarded by government forces

Starvation tactics

One of the most powerful weapons in this war has been its simplest: food.

All sides have cut off food, water, medicine in their quest for power.

Thirteen-year-old Kifah tried to put on a brave face when we met him in the besieged Palestinian camp of Yarmouk in 2014. But he soon collapsed in tears: "There was no bread."

Lyse Doucet visited Yarmouk in 2014: "They are absolutely desperate; desperate for help and desperate to get out"

Besieged residents of the Palestinian Yarmouk camp queuing for UN aid

One UN official said he has had to work hard to convince warring parties that wheat flour isn't used to make bombs.

But, in the words of a senior US official, President Obama has been "pathologically opposed to greater military involvement in Syria".

Without America firmly at the helm, Arab states and Turkey have backed different groups for different goals. In contrast, President Assad has had the most loyal of friends, including Russia, Iran and Lebanon's Hezbollah.

Millions of Syrians have been displaced inside the country, with many fleeing abroad

In the immediate wake of a strategic victory in the town of Qusayr in 2013, Hezbollah forces didn't hide their presence or pride. "How difficult were the battles," I asked some of the Lebanese fighters. "Easy-peasy lemon squeezy" one man replied with a grin.

Return to Deraa

Five years on, there is a rare, if fragile, truce, only because outside players finally decided to give peace a bit of a chance.

This month we went back to the city of Deraa, an unassuming agricultural area thrust into the headlines of history, to find a city drained by war.

The unprecedented protests of 2011 had morphed into the most significant assault by rebel forces known as the Southern Front to take the city last summer.

Governor Mohammad Khaled al-Hannus, whom we first met in 2011, showed us floors and windows gutted and shattered by rockets.

"We may have made some small mistakes," he admitted, but insisted the blame belonged firmly on the other side. "Their false revolution destroyed and divided our country."

Still protesting - an anti-government demonstration near Deraa during the truce

We reached by telephone a teacher named Zahra in rebel-held Deraa. "A lot was destroyed, but the revolution was inevitable," she told me. "So many fled because one man wants to stay in power."

Defiance and distrust are undiminished.

Syria is a different country now. Millions fled with their children to try to begin a new life elsewhere.

But Syria isn't lost - yet.

Somewhere in between a regime and a revolution a new Syria, with remnants of its old self, could still emerge from these ruins - but only if this war stops stealing its future.