As Iran waits for nuclear deal dividends - could the EU help?

- Published

Iran has seen a flurry of diplomatic activity after last year's nuclear deal

At a popular hotel in the Iranian capital they are kept busy changing the flags.

When we arrive in the early hours of Saturday, along with the largest EU delegation in more than a decade, the lobby is dominated by a table of pink lilies in glorious bloom fronted by Europe's 12-starred blue flag entwined with Iran's tricolour.

By lunchtime, India's flag is jostling for space in the display to welcome its foreign minister. And a Russian flag is at the ready for the imminent arrival of a trade mission from Moscow.

Later in the lobby there is a sudden tinkling on the ivories of an unexpected tune: the American anthem, The Star Spangled Banner.

Welcome to Tehran, three months after sanctions were lifted, and nearly a year after an historic nuclear deal that opened Iran's doors to the world.

But, aside from a small but growing number of American tourists flocking to enjoy Iran's spectacular heritage and hospitality, US businesses and officials are still staying away.

Their engagement in Iran is still blocked by US financial sanctions only the US Congress can lift. There is no sign of that happening.

And that is complicating matters for everybody.

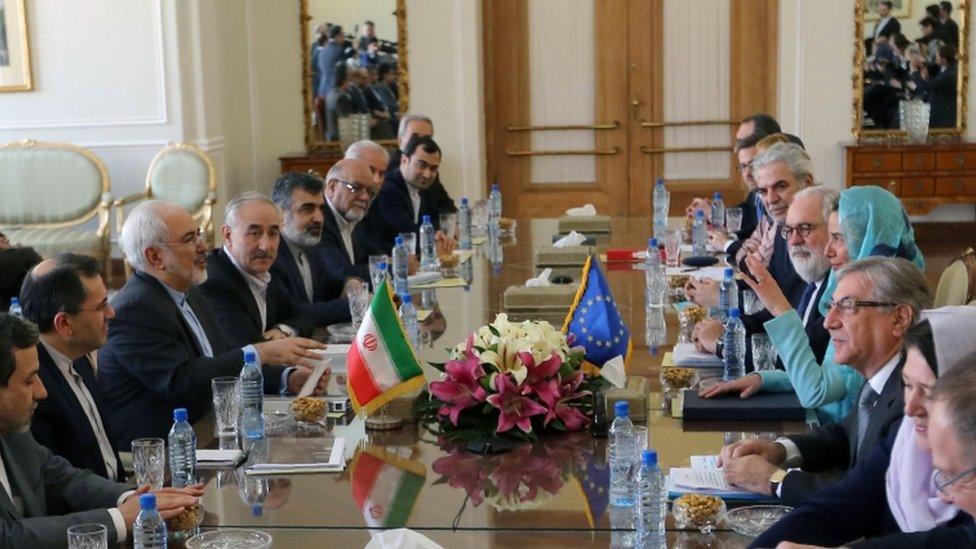

Ms Mogherini and Mr Zarif have hailed their recent talks as the most significant in many years

When EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini sweeps into Iran's elegant foreign ministry with a delegation of seven commissioners, she speaks of "turning the page" in Europe's relationship with Iran.

A beaming Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif hails a "new beginning".

Economic dividend

But, at that crowded news conference, Iranian journalists keep asking about US banking obstacles frustrating everyone - from individuals trying to make international bank transfers to potential investors seeking finance for deals.

"Europeans have as much of an interest as the Iranians that this issue is solved," Ms Mogherini assures them.

One of the EU's leading sanctions experts tells me European companies should not fear penalties linked to sanctions.

But major European banks and businesses, especially those with any US connections, are wary, still worried they will be unwittingly snared in the remaining web of regulations.

Ms Mogherini headed the largest EU delegation to visit Tehran in more than a decade

The sanctions linked to charges that Iran is "supporting terrorism", violating human rights, as well as concerns over its ballistic missile programme are still in place.

"Iran and the EU will put pressure on the United States to facilitate the co-operation of non-American banks with Iran," Mr Zarif emphasises.

Ms Mogherini is known to have even raised the issue with President Barack Obama. And a senior EU official says they are in touch with their US counterparts on these issues "on a daily basis".

US officials who played a key role in clinching the historic nuclear accord understand Iran's need to see an economic dividend from the deal.

But they are also adamant that they've kept their commitments under the agreement. They are also under pressure from Republican lawmakers implacably opposed to any opening at all.

At risk?

Another problem for investors eager to take advantage of an 80m-strong market is knowing who is who in Iran's opaque system.

When Mr Zarif sits down with me and three other journalists travelling with Ms Mogherini's delegation, he emphatically denies reports that more than half of Iran's economy is run by entities linked to "parastatal organisations" including the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) which is under both EU and US sanctions.

They are known to be involved in industries everywhere from oil to telecoms.

"I do not have exact figures but I can assure you that Iran's economy is huge and these proportions are totally disproportionate to reality," he replies.

"Much smaller than half of the economy?" we press him. "Certainly," he insists.

He says Iran will fulfil its obligations to engage with regulatory institutions on issues such as money laundering and financing of terrorism.

But despite his palpable concern, Mr Zarif does not echo the warning sounded by Iran's Central Bank Chief Valiollah Seif that the nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), was now in danger.

"The JCPOA is not in jeopardy," he says. But he cautions there is a risk.

"I believe Iranians are very hopeful about the future and see the benefits of engagement," he says. "But, if they do not see change, they will change their mind."

Change of tune?

In most conversations I hear in Tehran, there is this sense that hope still has not run out. "I was very happy when the nuclear deal was reached," says Shaghayegh, a young woman shopping in Tehran's bustling bazaar.

"It's had no effect yet, but I am sure it will gradually bring good things for everyone."

Another woman, Negin, expresses a similar sentiment: "The lifting of sanctions hasn't brought prices down as we hoped but, God willing, we will see results."

And in that hotel lobby I also keep meeting people with two tales to tell.

"I've been here five or six times," Pakistani industrialist Khurrram Sayeed tells me as he proudly holds up a newspaper with a front-page photograph of a large group of potential investors attending a petrochemicals conference.

"But it's all a hoax," he sighs. "Nothing is happening because we can't find the financing. Everything comes down to the US."

An Iranian man sitting nearby turns out to be a tour guide. "I have several groups of American tourists now," he says enthusiastically.

But his positive pitch also turns sour. "Half my European visitors recently cancelled," he adds.

His disappointment is linked to new US visa restrictions which require people who have travelled to certain Middle East countries, including Iran, to obtain visas to enter the US.

Even the pianist in the lobby changes his tune. His rendition of The Star Spangled Banner is soon replaced by something less politically risque - a popular Beatles ballad.