Sykes-Picot: The map that spawned a century of resentment

- Published

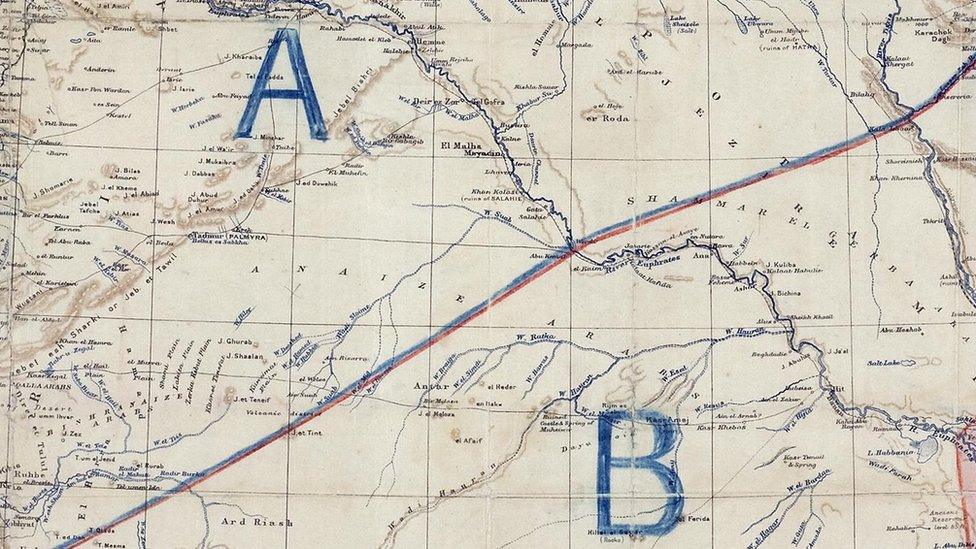

The 1916 map, with the signatures of Mark Sykes and Francois Georges-Picot

Reaching its centenary amidst a general chorus of vilification around the region, the legacy of the secret Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916 has never looked more under assault.

As Iraq lurches deeper into turmoil and disintegration, Kurdish leaders in the already autonomous north are threatening to break away and declare outright independence.

And the militants of the self-styled Islamic State (IS), bulldozing the border between Iraq and Syria in June 2014, declared their intention to eradicate all the region's frontiers and lay Sykes-Picot to rest forever.

Whatever the fate of IS, the future as unitary states of both Syria and Iraq - central to the Sykes-Picot project - is up in the air.

IS released a video in June 2014 of militants bulldozing berms on the Syria-Iraq border

In fact, virtually none of the Middle East's present-day frontiers were actually delineated in the document concluded on 16 May 1916 by British and French diplomats Mark Sykes and Francois Georges-Picot.

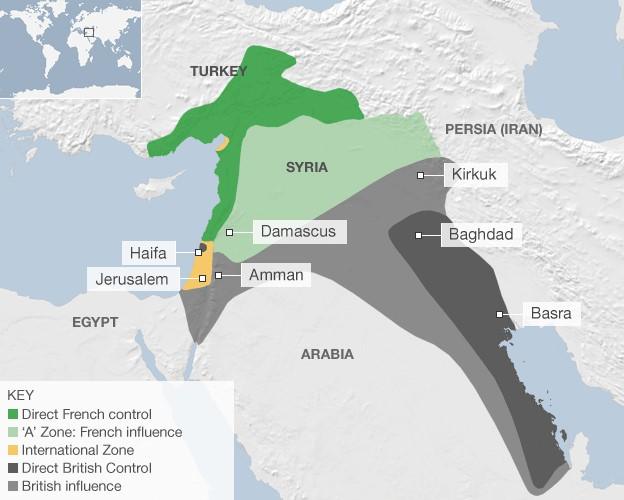

The Iraq-Syria border post histrionically erased by IS was probably several hundred kilometres from the famous "line in the sand" drawn by Sykes and Picot, which ran almost directly from the Persian border in the north-east, down between Mosul and Kirkuk and across the desert towards the Mediterranean, veering northwards to loop around the top end of Palestine.

Read more:

The region's current borders emerged from a long and complex process of treaties, conferences, deals and conflicts that followed the break-up of the Ottoman Empire and the end of World War One.

But the spirit of Sykes-Picot, dominated by the interests and ruthless ambitions of the two main competing colonial powers, prevailed during that process and through the coming decades, to the Suez crisis of 1956 and even beyond.

Kurdish hour?

Because it inaugurated that era, and epitomised the concept of clandestine colonial carve-ups, Sykes-Picot has become the label for the whole era in which outside powers imposed their will, drew borders and installed client local leaderships, playing divide-and-rule with the "natives", and beggar-my-neighbour with their colonial rivals.

The resulting order inherited by the Middle East of the day sees a variety of states whose borders were generally drawn with little regard for ethnic, tribal, religious or linguistic considerations.

Often a patchwork of minorities, there is a natural tendency for such countries to fall apart unless held together by the iron grip of a strongman or a powerful central government.

The irony is that the two most potent forces explicitly assailing the Sykes-Picot legacy are at each other's throats: the militants of IS, and the Kurds in the north of both Iraq and Syria.

In both countries, the Kurds have proven the Western coalition's most effective allies in combating IS, although the two sides share a determination to redraw the map.

"It's not just me that's saying it, the fact is that Sykes-Picot has failed, it's over," said the president of Iraq's autonomous Kurdistan Region, Massoud Barzani, in a BBC interview.

"There has to be a new formula for the region. I'm very optimistic that within this new formula, the Kurds will achieve their historic demand and right [to independence]".

Massoud Barzani believes Kurds will eventually obtain a permanent nation state

"We have passed through bitter experiences since the formation of the Iraqi state after World War One. We tried to preserve the unity of Iraq, but we are not responsible for its fragmentation - it's the others who broke it up.

"We don't want to be part of the chaos and problems which surround Iraq from all sides."

Entity with borders

President Barzani said the drive for independence was very serious, and that preparations were going ahead "full steam".

He said the first step should be "serious negotiations" with the central government in Baghdad to reach an understanding and a solution, towards what Kurdish leaders are optimistically calling an "amicable separation".

If that did not produce results, he said, the Kurds should go ahead unilaterally with a referendum on independence.

Kurds have declared the establishment of a federal system in areas they control in Syria

"It's a necessary step, because all the previous attempts and experiments failed. If current conditions aren't helpful for independence, there are no circumstances which favour not demanding this right."

Iraq's Kurds are landlocked and surrounded by neighbours - Syria, Turkey, Iran and Iraq itself - which have traditionally quashed Kurdish aspirations.

Under threat from IS, they are more dependent than ever on Western powers which are also strongly counselling them to stick with Iraq.

But whether or not the Iraqi Kurds achieve full formal independence in the near future, they have already established an entity with borders, a flag, international airports, a parliament and government, and its own security forces - everything except a passport and their own currency.

To that extent, they have already redrawn the map. And next door in northern Syria, their fellow Kurds are essentially doing the same, controlling and running large swathes of land along the Turkish border under the title of "self-administration".

Redrawing the future

As for IS, its territorial gains have already peaked. But the chaos in both Iraq and Syria that allowed it to take root have yet to run their course - the alienation of Iraq's Sunni Arab minority (and the Kurds), and Syria's fragmentation in a vicious sectarian civil war.

The map was drawn with a line from Persia to the River Jordan

The unspoken struggle is over whether formulas can be found for different communities to live together within the borders bequeathed by 20th Century history, or whether new frontiers will have to be drawn to accommodate those peoples - however that concept is defined.

"Sykes-Picot is finished, that's for sure, but everything is now up in the air, and it will be a long time before it becomes clear what the result will be," said the veteran Lebanese Druze leader Walid Jumblatt.

The Sykes-Picot agreement conflicted directly with pledges of freedom given by the British to the Arabs in exchange for their support against the collapsing Ottomans.

It also collided with the vision of the US President Woodrow Wilson, who preached self-determination for the peoples subjugated by the Ottoman Empire.

His foreign policy adviser Edward House was later informed of the agreement by UK Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour, who 18 months on was to put his name to a declaration which was to have an even more fateful impact on the region.

House wrote: "It is all bad and I told Balfour so. They are making it a breeding place for future war."

- Published1 June 2015

- Published14 December 2013