Iraq's Sinjar Yazidis: Bringing IS slavers to justice

- Published

Hundreds of Yazidi women have been forced into sexual slavery by the self-style Islamic State.

Two years ago this week, an atrocity helped launch the international campaign to turn back the advance of so-called Islamic State (IS). Thousands of terrified villagers fled for their lives near Mount Sinjar in northern Iraq, as heavily armed IS fighters attacked their ancestral homeland.

The victims were Yazidis, an ancient community considered heretical or even sub-human by IS jihadists. Hundreds fled up the mountainside where many died in the scorching heat.

Most of the men of fighting age who were captured were summarily slaughtered.

For the women and girls rounded up by IS, a living hell awaited.

For Bill Wiley, the chief investigator at the Commission for International Justice and Accountability, it is clear that IS had sex slavery in mind.

He says: "The evidence is overwhelming that Islamic State forces went into Iraq in mid-2014 with a plan to enslave Yazidis, those that they did not murder, and to traffic these women and girls into sexual slavery."

This Yazidi family got away from IS but women who were captured faced a terrible fate

Slave-owners identified

Funded by the Canadian and German governments, a team of experienced war crimes investigators has so far identified 49 slave-owners and a further 34 men holding senior positions in the IS infrastructure.

It is these "policy-makers" the team are focusing on, as they hold them responsible for a systematic enslavement that saw women forcibly trafficked across northern Iraq and Syria.

Mr Wiley was shocked by the way IS treated Yazidi women and girls

A quietly spoken Canadian, Mr Wiley has worked in war zones from the Balkans to the Congo. Yet he told me that nothing had prepared him and his researchers for the calculated cruelty meted out to Yazidi women and children.

"We're talking hundreds and hundreds of women who have been seized by Daesh," he said, using another name for IS.

"And indeed we're not just talking about women, we're talking about girls of 10, 12, 14 years old, who now for a period of two years have been held in custody by individual slave owners. They're raped again and again and again."

'I want two slaves'

Last year a video appeared, filmed by IS members themselves, showing their fighters excitedly discussing the "Souq Al-Sabaya" - the female slave market.

"Where is my Yazidi girl?" demands one of them.

"I want two," says another.

"If she has blue eyes I'll pay more," says a third.

One of the men tries to justify their intentions by proclaiming that the slave market or auction has "been ordained".

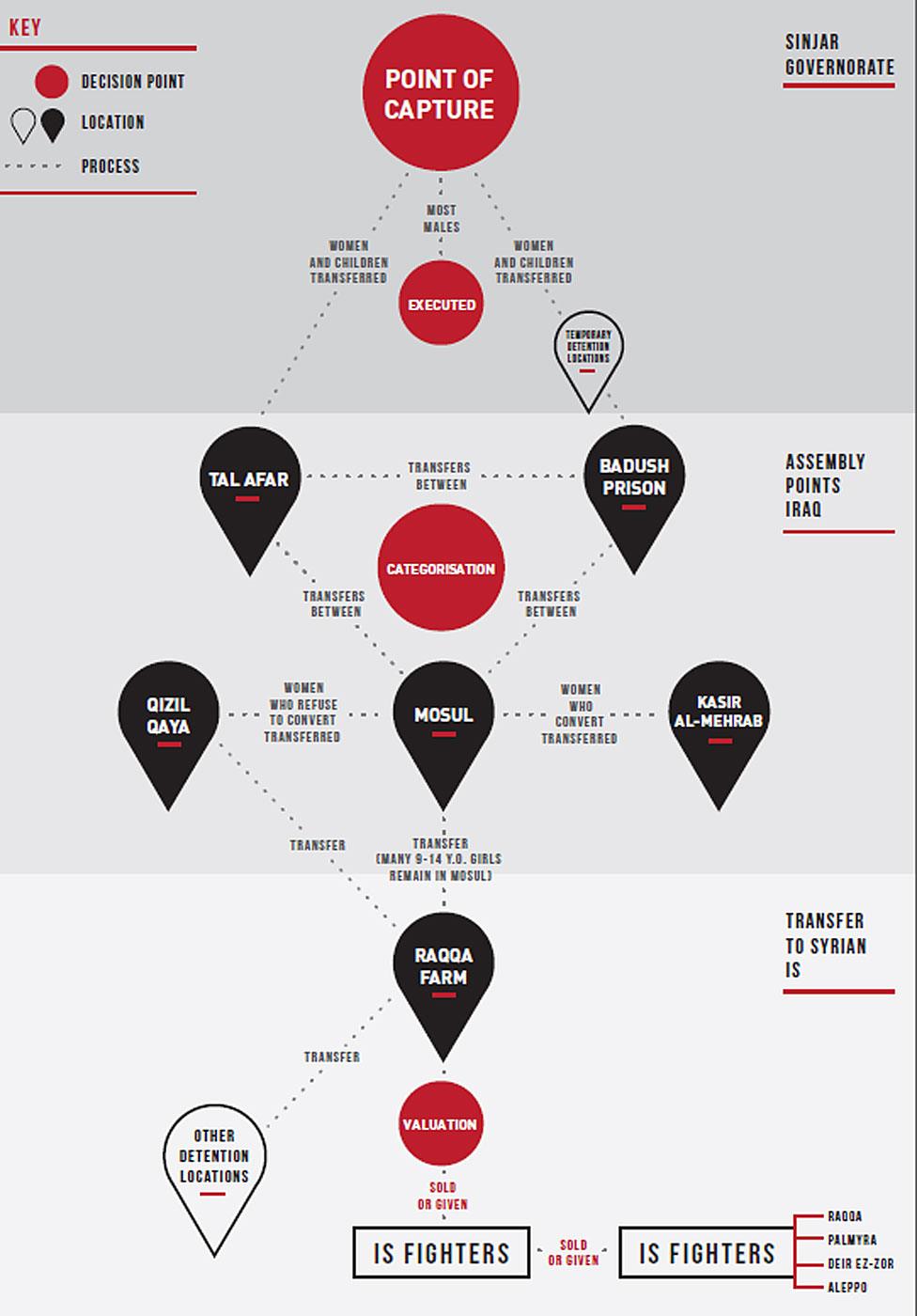

The investigators have compiled a flow chart showing the organised passage of IS slaves, from where they were caught near Mount Sinjar, to Tal Afar or Badush Prison in northern Iraq, then on to Mosul where they are categorised into those prepared to convert to Islam and those who refuse.

Even conversion, say the investigators, has not spared many of them from sex slavery.

From there, according to the flow chart, the women and girls as young as nine are transferred to a market at Raqqa Farm where they are '"valued".

Some are traded for as little as £10 ($13), others fetch as much as £5,000 ($6,680) and some are simply "gifted" to IS fighters without the means to buy them. Two years on from their initial capture, hundreds are still believed to be enslaved.

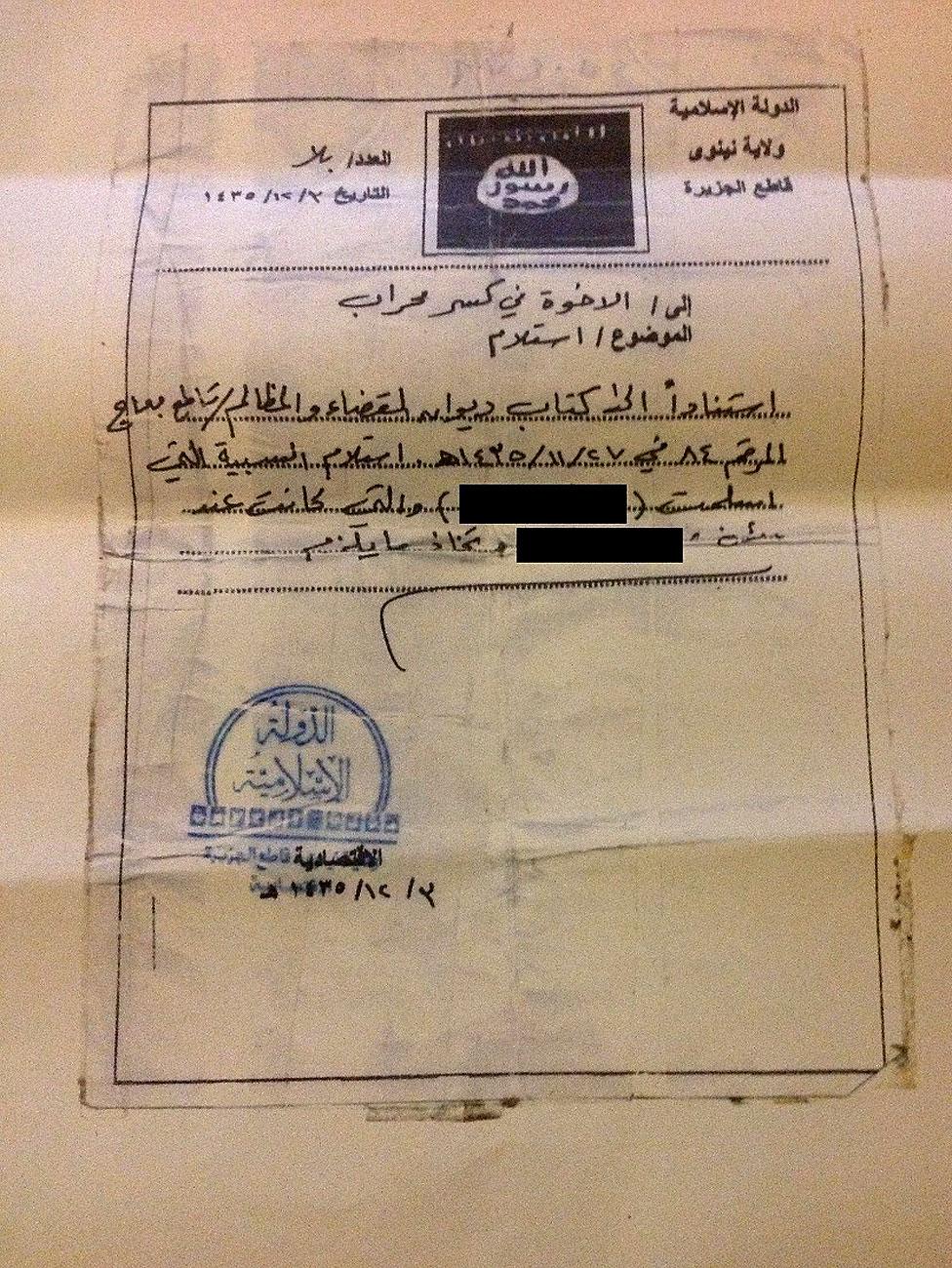

Redacted document with IS crest and stamp showing how a slave was officially freed by a Sharia court

'Not soldiers of Mohammed'

Mr Wiley wants those responsible to face trial, not as terrorists, but as common criminals.

"We need to show that these men are criminals," he says.

"They're not soldiers of the caliphate or soldiers of Mohammed. They are not fighting for Islam, they're criminals. And we need to disassociate them in Western, but more importantly in Arab minds, from mainstream Islam".

But it is one thing to gather evidence for a prosecution case, it is quite another to bring that suspect out of a warzone and into an internationally recognised court of law.

The investigators are hoping such a court will eventually be established in Irbil, in Iraqi Kurdistan, but they acknowledge this could still take some time.

So I put it to the man who heads their Daesh Criminal Investigations Unit (DCIU), who asked to be identified simply as "Jim" - was there not a risk that all their hard work would eventually be in vain?

"It is often the case that justice comes after the cessation of hostilities," he replied.

"What would be worse is if we didn't do this job and we came to a situation at the end of the conflict that these individuals were able to walk freely in Syria and Iraq and across the globe, because no-one had had the time and the foresight and the hope in justice to engage in this process now."

Time is probably not on the side of the alleged offenders.

Some, like a man identified as Abu Alaa Al-Afri, a former school teacher who went on to become "the Emir of Sinjar", are believed to have been killed in the ongoing fighting in Iraq.

Others, such as Hajji Bakr - not to be confused with the top IS commander killed in Syria in January 2014 - are still believed to be alive and at large.

Hajji Bakr

Some may look to escape the region, possibly to Europe.

But others may well now find themselves on a wanted list as coalition special forces increasingly mount raids into IS territory.

Bringing those responsible for war crimes in Rwanda and Yugoslavia took many years. Bill Wiley and his team are hoping their efforts will considerably shorten that time when it comes to the crime of sexual enslavement in northern Iraq.

- Published14 July 2015

- Published19 March 2015

- Published22 December 2014

- Published20 August 2015

- Published8 August 2014

_cut.jpg)