Mosul: Iraq's beleaguered second city

- Published

Mosul was Iraq's second largest city when Islamic State (IS) militants overran it in June 2014, routing the Iraqi army and sending shockwaves around the world.

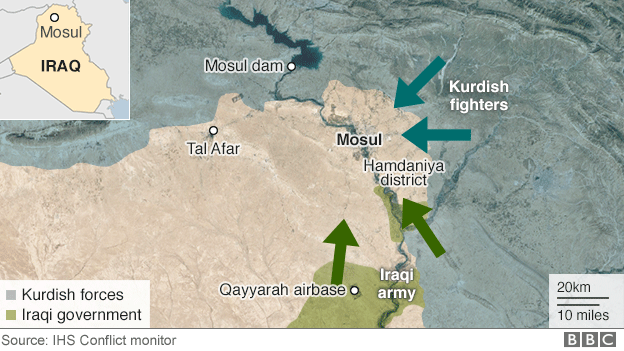

More than two years later, Iraqi security forces have launched a major offensive to retake it with the support of Kurdish Peshmerga fighters, Shia paramilitary forces, Sunni tribesmen and US-led coalition air strikes.

Before it fell to IS, the oil-rich capital of Nineveh province was the political, economic and cultural centre of north-western Iraq.

Its 1.8 million population was one of Iraq's most diverse, comprising ethnic Arabs, Kurds, Assyrians and Turkmens, as well as many religious minorities.

Mosul's Great Mosque, built in the 12th Century, is famous for its leaning minaret

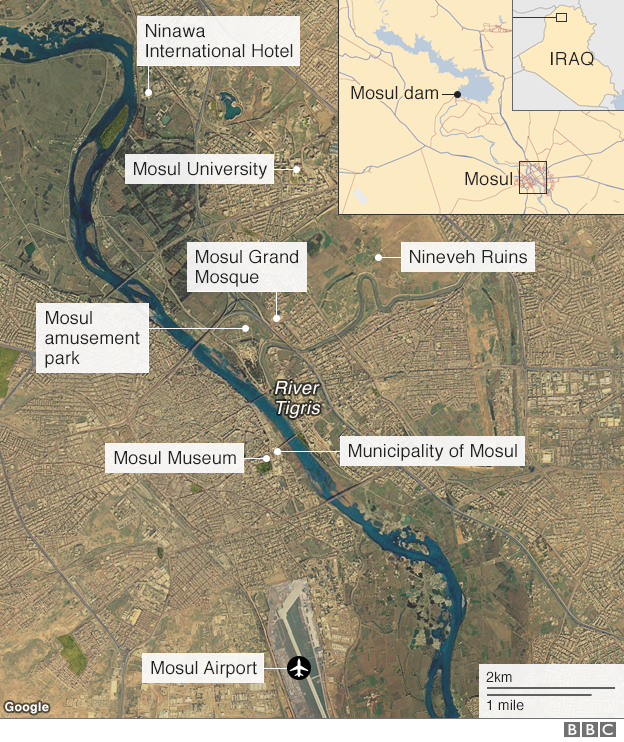

Mosul - meaning "the link" in Arabic - was established on the western bank of the River Tigris in the 6th Century, just across the water from the ancient Assyrian site of Nineveh, whose ruins it eventually encircled.

By the time of the Abbasid caliphate in the 8th Century, Mosul had become the principal city of northern Mesopotamia and a major trading centre. Its most famous export was a fine cotton fabric that European merchants called "muslin", derived from the city's name.

In 1262, Mosul was sacked by the Mongols under Hulagu, a grandson of Genghis Khan, after an almost year-long siege during which its inhabitants suffered greatly.

In the 16th Century, Mosul fell to the Ottoman Turks. Under their rule, the city once again thrived and became an administrative and commercial hub.

Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War One, Mosul and its surrounding province were occupied by British forces. In 1926, they became part of mandatory Iraq as a result of a border settlement with the new Turkish state.

At the same time, Mosul benefited considerably from the development of oilfields in the region. It also became a centre of cement, textile and sugar production.

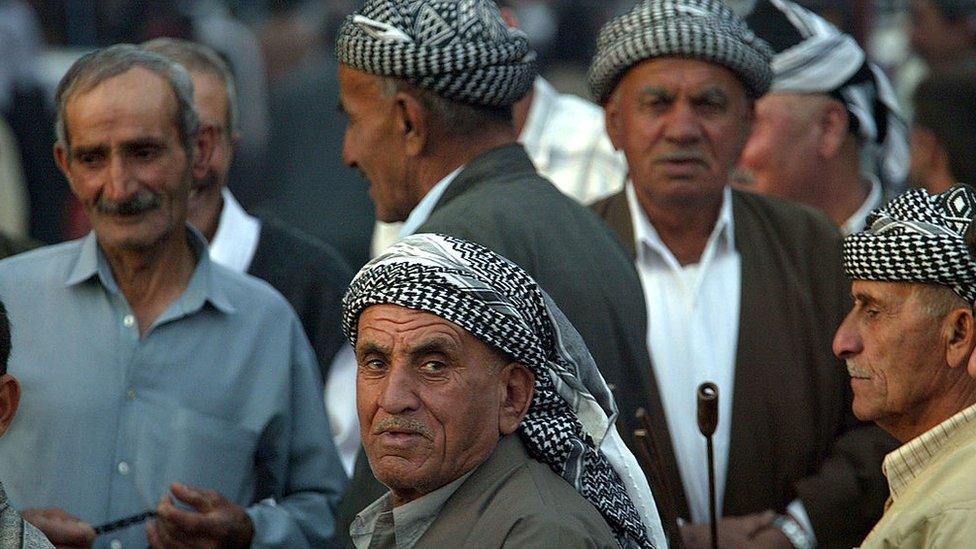

Successive governments pursued a policy of Arabization in Mosul, displacing the city's Kurds

After Iraq gained independence in 1932, successive governments attempted to "Arabize" Mosul and other areas of northern Iraq, by forcibly displacing hundreds of thousands of ethnic Kurds, Turkmens and Assyrians, and encouraging landless Arabs from central and southern Iraq to resettle there.

The policy was stepped up by Saddam Hussein's Baath Party in the 1970s and continued until the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, after which many Kurds and other non-Arabs sought to reclaim property that they said had been expropriated by the government, increasing ethnic tensions.

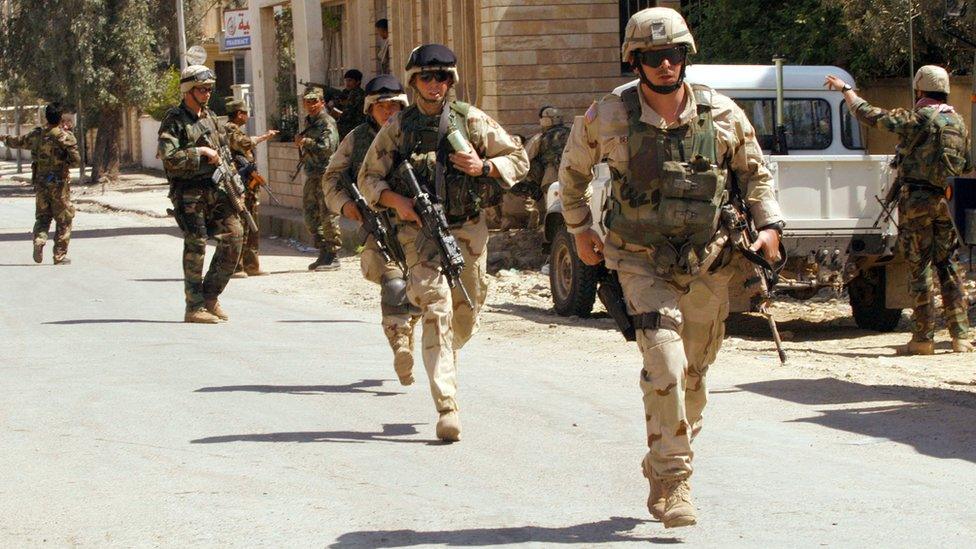

Mosul fell to US and Kurdish forces in April 2003

Kurdish Peshmerga fighters also took control of several nearby towns and villages, seeking to incorporate them into the autonomous Kurdistan Region, and a Sunni Arab boycott of the 2005 provincial elections led to Kurdish parties governing Nineveh for four years.

The Kurdish gains helped turned Mosul into a bastion of resistance to the US occupation, resulting in years of bombings and shooting by militants from al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) - a precursor to IS - and former Baath Party loyalists who portrayed themselves as defenders of Arab interests.

In 2007, many AQI members relocated to Mosul after US and Iraqi troops and Sunni Arab tribesmen launched operations to drive them from provinces to the south and west. Mosul's proximity to Syria also meant that it was a conduit for foreign fighters.

Mosul became a bastion of resistance to the US occupation

It was not until 2009 that a semblance of normality returned to Mosul, but jihadists maintained a firm hold and it was still one of Iraq's most dangerous cities.

Sectarian violence increased once again after US troops withdrew from Iraq in late 2011, and surged in early 2013 when Shia Arab Prime Minister Nouri Maliki ordered an offensive against AQI while also moving against Sunni Arab protesters, who were angered by his government's sectarian policies.

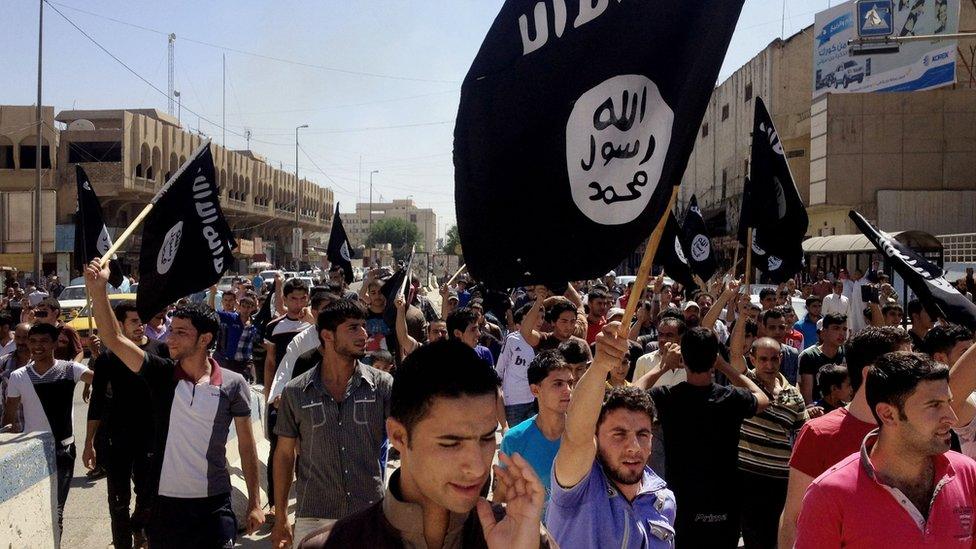

Many Sunni Arabs in Mosul initially welcomed the arrival of Islamic State militants

In June 2014, emboldened by their capture of the western Iraqi city of Falluja six months earlier and subsequent battlefield successes in Syria's civil war, militants from what was then known as Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Isis) launched an assault on Mosul. Between 10,000 and 30,000 soldiers and police dropped their weapons and fled when confronted by as few as 800 militants.

The militants then swept southwards, taking control of much of Nineveh and two neighbouring provinces in a matter of days. Half a million people fled their homes to escape the onslaught.

Days later, Isis declared the establishment of a "caliphate" - a state governed in accordance with Islamic law, or Sharia, by God's deputy on Earth - and changed its name to "Islamic State".

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi enjoined Muslims to emigrate to IS territory at Mosul's Great Mosque

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi then made his first public appearance in many years, delivering a sermon at Mosul's Great Mosque in which he enjoined Muslims to emigrate to IS territory.

Initially, many Sunni Arab residents of Mosul appeared to welcome the militants.

But opposition grew as they experienced more than two years of brutal IS rule, during which there were public beheadings and amputations, smoking was banned and women were forced to cover themselves in public. People also complained of IS surveillance and extortion, as well as shortages of water, electricity and fuel.

Mosul diary: 'I feel like I'm living in a prison'

There was also outrage when IS began destroying Mosul's cultural heritage, when videos emerged showing renowned Muslim and Christian sites being razed to the ground, antiquities inside the Mosul Museum smashed up, and colossal statues on Nineveh's ancient Nergal Gate demolished.

By the time that Iraqi government forces were ready to launch an offensive to retake Mosul in October 2016, some of the one million people estimated to be still living in the city had begun openly resisting IS rule.

Two men were beheaded, external after a number of walls in the city were spray-painted with the letter "m", standing for "resistance" in Arabic, and more than 50 people were also reportedly summarily killed for their role in a rebellion plot, external.

The estimated 3,000 to 5,000 militants left in Mosul have prepared, external to defend the city by digging tunnels, rigging bridges with explosives, preparing car bombs and recruiting children as spies, Iraqi and US officials said.

Are you in the region around Mosul? Are you from Mosul? Let us know about your experiences. Email haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external with your stories.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also contact us in the following ways:

·WhatsApp: +44 7525 900971

·Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

·Send an SMS or MMS to +44 7624 800 100

- Published15 October 2016

- Published15 October 2016