Can dealmaker Trump seal Middle East peace?

- Published

The world is waiting to see where Donald Trump stands on complex issues in the Middle East

A president-elect who prides himself on the "art of the deal" is about to confront a mire in the Middle East where deals are sorely needed, but so very hard to clinch.

Across the Middle East and beyond, many are pondering Mr Trump's declarations in the heat of the campaign, his still sketchy comments in sit-down interviews, and his first choices for his team in White House Inc.

Last week's Sir Bani Yas Forum in Abu Dhabi, an annual gathering of foreign ministers and prominent regional experts, provided a snapshot of the uncertainties and ambiguities before Mr Trump formally takes charge on 20 January.

A respected US commentator derided a businessman without experience in governing who "discovers our policies while speaking." He summarised Mr Trump's foreign policy thinking as "contradictory impulses."

Others urged everyone to "give him time."

"He likes to do deals, so there could be opportunities," remarked an Arab ambassador.

So unpredictable is the man about to assume the mantle of the world's most powerful president that one policy expert warned "he could open hotels in Iran or go to war with Iran".

Diplomats are unsure whether the next US leader will bomb Iran or pursue business there

The region presents the property tycoon turned President-elect with a number of complex deals to try to strike: end a devastating war in Syria; resolve a destructive conflict in Yemen; untangle the geopolitical knots which harden these tensions and are threaded through parallel wars against so-called Islamic State (IS) and Al Qaeda-linked groups.

Mr Trump has already cast his eye on the most elusive agreement of all - an Israeli Palestinian peace accord.

"That's the ultimate deal," he told the Wall Street Journal in an interview shortly after his electoral victory. "As a dealmaker, I'd like to do... the deal that can't be made."

But its the nearly six-year-long conflict in Syria which is likely to be his first test.

In his latest and most extensive interview, with a group of New York Times editors and reporters, the president-elect seemed to hint at greater engagement than his so far single focus on defeating IS. But it was still bereft of details or depth.

When asked what he would do about the Syria conflict he replied: "I can only say this: we have to end the craziness that's going on in Syria."

Then, intriguingly, he asked to go off the record about "one of the things that was told to me."

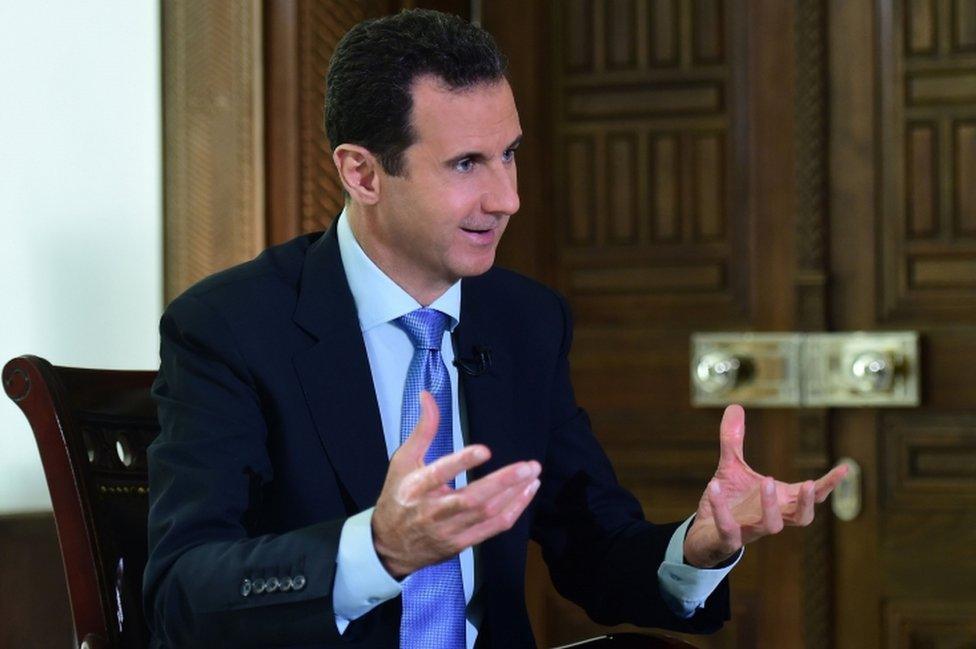

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad said he remains "cautious in judging" Mr Trump

Over the past year, Mr Trump repeatedly said he would team up with Russia and its ally President Bashar al-Assad to take on IS. Ending extremist groups' control of territory in Syria and Iraq is also one of President Obama's principle aims, which is now making progress.

But Mr Trump has been publicly nailing his colours to a different mast.

"I'm not saying Assad is a good man, because he's not," Mr Trump told The New York Times in an interview earlier this year. "But our far greater problem is not Assad, it's ISIS," he said, using an alternative name for IS.

As for the US-backed rebels, he's said "we have no idea who these people are".

"Wait until he gets his first intelligence briefing," cautioned one Western analyst at the Forum hosted by the UAE's Foreign Minister Sheikh Abdullah Bin Zayed.

"Will he really want to abandon the rebels, especially when he realises that Russia spends more time attacking them, rather then IS?"

What Trump victory means for the world

Mr Trump has made no secret of his admiration for strongmen including Russia's President Vladimir Putin, arguably the most influential dealmaker now when it comes to crises like Syria.

Before Mr Trump's electoral victory, I asked a senior State Department official which options for Syria would be presented to the next administration.

The response: "It depends on what kind of relationship we want with Russia."

A Russian expert at the Abu Dhabi Forum predicted that Hillary Clinton's defeat meant a step back from what could have been "a kinetic collision in Syria."

He said President Putin and Mr Trump speak the "same language," but could still be pulled apart by conflicting interests.

And Mr Trump will face stiff resistance in the US Congress, where prominent Republicans like Senator John McCain denounce the Russian and Syrian bombing as "barbaric".

Mr Trump must decide what kind of relationship he wants with Putin's Russia

There are wars within wars in Syria. Strengthening the Putin-Assad axis would also bolster Iran, a country Mr Trump repeatedly warned he would "get tough with".

Turkey's President Erdogan may also be the kind of authoritarian leader Mr Trump is drawn to, but he also has strong red lines in neighbouring Syria, most of all stopping the advance of Syrian Kurdish groups the US is now relying on to fight IS in northern Syria.

The president-elect has also threatened to tear up "bad" deals, including Iran's nuclear agreement, which limits Tehran's nuclear programme in exchange for sanctions relief.

"Only someone who wants to send us into an unknown world would tear it up," remarked a senior Gulf Arab official.

It's Iran's influence and interventions across the region that most Arab states, and Israel, want to stop. President-elect Trump is likely to find support in the Republican-dominated Congress to move in that direction.

For now, most Arab leaders appear to be keeping an open mind about the man soon to lead their most important foreign ally.

They've been bitterly frustrated by President Obama's reluctance to intervene more forcefully in Syria, and his efforts to ease Iran's isolation.

The president-elect has promised to end what he calls "bad" deals, including Iran's nuclear agreement

Syria's opposition leaders and activists are still hoping Mr Trump will revise his first simplistic draft of his Syria policy.

"If he wants a partner to fight IS, he will find one in us," former opposition spokeswoman Bassma Kodmani told me in a recent interview.

But for some activists, there's a growing worry that nearly six years into a punishing war, ending President Assad's rule will become even less of a priority for the US. The Syrian leader has already said Mr Trump could possibly be "a natural ally."

Once in office, a president-elect who says he makes decisions by instinct will be held in check by what's often invoked as the "system:" US lawmakers; the security establishment; vested interests and new views across his administration.

What is, for many, a surprising ascent to power is likely to keep bringing surprises.

- Published2 December 2016

- Published9 November 2016