Obama and the Middle East - too little, too late?

- Published

Why now? What's the Obama administration playing at? Isn't it all a bit too little and much too late?

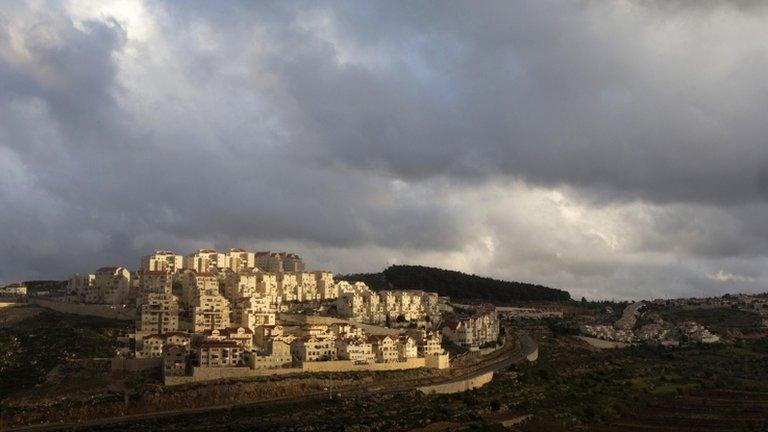

There's been much scratching of heads since the US took the unusual step of allowing a resolution condemning Israel's settlements policy to pass the UN Security Council last week.

And since John Kerry's speech on Wednesday, Obama's critics have spoken out against the president and his secretary of state for something they see as an unwarranted betrayal.

The former US diplomat Elliott Abrams, writing in the conservative Weekly Standard, called the speech "the last defence of a policy that has achieved nothing except damaging bilateral relations".

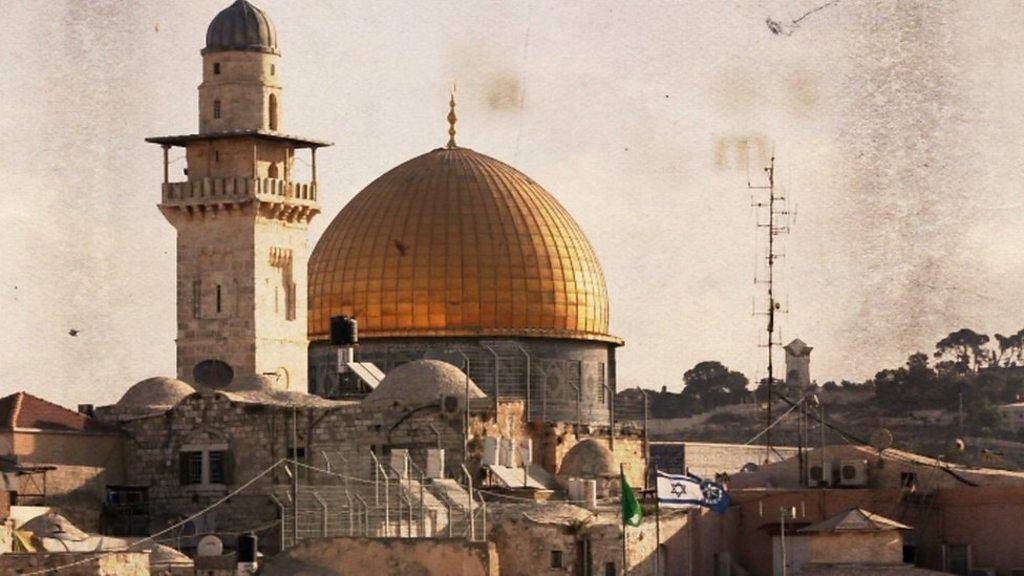

Others suggested that while there was nothing remotely original about the solutions Mr Kerry offered - anyone familiar with recent decades of Arab-Israeli diplomacy will have recognised the formulas on settlements, Jerusalem, refugees, etc - the timing rendered the whole exercise futile.

Israel's Prime Minister Banjamin Netanyahu strongly criticised John Kerry's speech

In The Times of Israel, journalist Avi Issacharoff, external, said Mr Kerry had set out principles "any reasonable person…knows will form the basis for any future negotiations between the parties".

But as someone who had welcomed the Obama administration's early efforts to secure a breakthrough between the Israelis and Palestinians, Issacharoff said Kerry and Obama had allowed the two-state solution to "fade from history".

"Perhaps it was Benjamin Netanyahu who broke his spirit, perhaps [Palestinian president] Abbas. Maybe both. But Kerry and the US government raised the white flag," focusing instead on securing a nuclear deal with Iran, he wrote.

It's certainly true that President Obama's early intensive efforts came to nothing. And it seems likely that a poisonous relationship with the Israeli leader was one factor.

But in truth, the Arab-Israeli "peace process" had been moribund for years before Barack Obama took office.

It would have taken something fairly miraculous to revive it.

The Arab spring, the toppling of regimes and the subsequent wars in Libya and Syria also appeared to give the White House and State Department more pressing things to think about.

Obama's pursuit of the Iran nuclear deal also deepened Mr Netanyahu's hostility.

Mr Netanyahu has openly praised Donald Trump - in contrast to his relationship with Obama

The Arab-Israeli conflict didn't seem to be going anywhere. Of course, there was violence - in the Gaza-Israel conflict in the summer of 2014 and the "knife intifada" which began in late 2015 and lasted into this year.

But with the wider Middle East going up in flames, this seemed little more than the latest manifestation of an all-too familiar pattern.

However as John Kerry noted, the reality on the ground has steadily deteriorated.

What might just seem like more of the same - violence, incitement and the growth of Jewish settlements on occupied land - is in fact burying all prospect of a negotiated settlement and a two-state solution.

"The status quo is leading towards one state and perpetual occupation," he said.

US Secretary of State John Kerry: "The two-state solution is now in serious jeopardy"

Mr Kerry's speech was long and frequently passionate. His strong convictions - and his deepest fears - were much in evidence. Rarely has an American official spoken with such clarity or fervour.

So what?

With just three weeks to go before Barack Obama leaves office, and with a strongly pro-Israel president-elect breathing down his neck (usually via Twitter, external), what's the point of merely decrying the world as it is? After years of inaction, can this late intervention possibly do any good?

Outgoing presidents have occasionally felt the need to set out their Arab-Israeli stall before stepping down and handing the keys to the White House to their successor.

Bill Clinton did it in December 2000, announcing a set of "parameters", similar in tone but more detailed than the principles outlined towards the end of John Kerry's speech.

These were followed, in late January 2001, by the Taba Summit, which brought Israeli and Palestinian negotiators closer to an agreement than they had ever been.

Israeli PM Ehud Barak met Bill Clinton at the White House to appeal for peace - weeks before Mr Barak's electoral defeat

But Bill Clinton's departure from office was followed, within weeks, by Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak's defeat at the polls.

With the second Palestinian uprising raging and a new, more hawkish Israeli leader, Ariel Sharon, in power, the Taba accord was quickly forgotten: a tantalising glimpse of what could have been.

As it happens, a peace conference is looming this time too.

Representatives from dozens of countries will meet in Paris in mid-January and it's been suggested that agreements reached there could find their way into another UN Security Council resolution, before Donald Trump takes office.

But the omens are not good. Taba was everything Paris will not be: intimate and detailed.

As the Taba talks wrapped up, a senior Palestinian official told me that for the first time, his side had perceived the outlines of a viable future state.

Could the Paris talks result in a blueprint, followed by an international seal of approval from the UN?

Possibly, but with Donald Trump telling Israel to "stay strong" and promising much more robust support for Prime Minister Netanyahu, the most right-wing government in Israel's history may simply decide to sit on its hands and wait for the storm to pass.

- Published1 July 2016

- Published21 March 2013

- Published4 May 2016

- Published22 October 2015

- Published28 December 2016

- Published15 October 2015

- Published28 December 2016

- Published29 December 2016