Ceasefire in Syria: Turkish policy sets Syria on new path

- Published

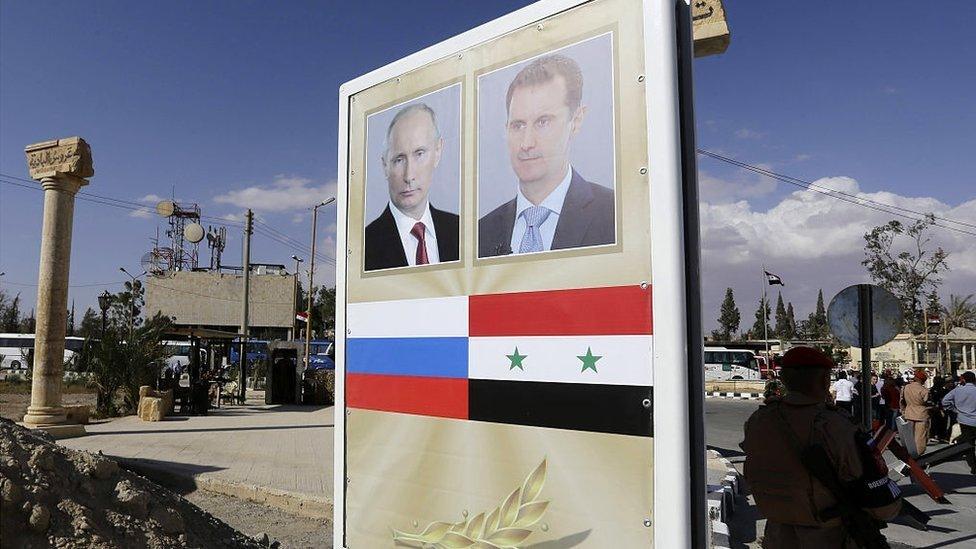

Turkish President Erdogan (L) and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin (R) have become unlikely allies

If the ceasefire brokered by Russia and Turkey holds, it will be welcomed by most people in Syria - but the odds seem stacked against it.

Several previous ceasefires have collapsed, and new clashes have already broken out in several parts of the country amidst sharp differences in interpretation of the latest agreement by the Syrian opposition and the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

But not all past ceasefire attempts have failed. And this time dramatic shifts in Turkish policy towards the Syrian conflict may alter everything.

Political investment by major external powers is clearly critical for any ceasefire deal to succeed.

The "cessation of hostilities" that was brokered by the US and Russia in February 2016 produced a major drop in levels of violence in all regime- and opposition-held areas for some two months.

Its eventual collapse was likely, but not inevitable.

East Aleppo is calm, but evidence of its violent recent past is everywhere in the city

Other, more localized ceasefires were mediated by Iran in the city of Homs in May 2014 and January 2015 and by Iran and Turkey in the large towns of Zabadani, Foah and Kefraya in September 2015.

These were flawed and highly coercive arrangements that had to be renegotiated repeatedly, but they allowed the evacuation of fighters and wounded and some supply of humanitarian assistance.

Russia and Turkey appear sufficiently invested politically to make the latest ceasefire work.

But in seeking to encompass all parts of Syria not under Islamic State control, they are hostage to the two parties that have the least stake in a general truce: the Assad regime and Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, formerly known as Jabhat al-Nusra until ending its formal affiliation to Al-Qaeda last July.

Their gradual military escalation and counter-escalation was the principal reason for the ultimate collapse of the February cessation of hostilities agreement.

Already, the Assad regime has claimed that the latest ceasefire does not include Jabhat Fateh al-Sham. But opposition spokesmen say the opposite: that only areas under IS control are excluded.

The regime has lost no time since the ceasefire went into effect to mount fresh air strikes on areas north of the city of Hama known to be strongholds of Jabhat Fateh al-Sham.

The latter organisation has been striving for much of 2016 to become the dominant opposition force in the northwest of the country, and so there is a real risk that it will use the resumption of fighting as a means of splitting or radicalizing other rebel groups and bringing them under its fold.

Russia has sought to contain this issue by isolating Jabhat Fateh al-Sham from the rest of the armed opposition. Its announcement that the Islamist Ahrar al-Sham rebel movement, which it had previously designated as a terrorist jihadi group, had signed up to the ceasefire is a measure of how determined it is to make the agreement hold.

But the critical factor is the shift in Turkey's policy on Syria.

Previously, other armed opposition groups would have abandoned the ceasefire if Jabhat Fateh al-Sham came under attack.

Their dependence on its combat expertise and planning and command skills and the extensive intermingling of opposition fighters and areas of control in northwest Syria meant that they could not afford to stand by while it was targeted.

But with Turkey now coordinating closely with Russia and pushing for a ceasefire, the opposition can no longer afford not to stand by.

Russia's commitment to its relationship with Syria has been central to its intervention

Turkish policy has been evolving at a quickening pace. The decision to lean on the opposition to allow thousands of its fighters to abandon the effort to lift the regime siege of eastern Aleppo in order to spearhead a Turkish-backed push against Kurdish-held areas to the north last August ensured the fall of one of the most important opposition strongholds in Syria four months later.

Remaining opposition forces in the northwest have significant stockpiles of weapons and ammunition, but are wholly dependent on Turkey for further military resupply and for the flow of trade and international humanitarian assistance.

Turkey has not abandoned the opposition completely, but it is clearly working to a new set of policy assumptions and objectives in Syria. That these include a strategic decision to abandon the effort to force Assad from power is already plain.

Talk of setting up a safe zone in northern Syria has never been credible, despite considerable bluster. Moscow insiders claim Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is also abandoning his categorical rejection of significant Kurdish autonomy in northern Syria, so long as he can block the same thing in Turkey.

With President-Elect Donald Trump about to take office in the US, there is little reason for Turkey to expect to counter-balance Russian policy proposals on Syria.

President Assad - whose picture is seen at the centre of a Damascus peace vigil - now has far less reason to worry about Turkey

These calculations prompted Turkey to accept the fate of Aleppo - which it had long presented as a "red line" that the Assad regime should not cross - and then to broker a ceasefire with Russia immediately after its fall.

The alacrity with which the main political and military opposition groupings have announced their support for the latest ceasefire is the surest measure of the extent of the shift in Turkey's policy and of its determination to enforce compliance, whatever the provocations from the government side.

The real question, then, is not whether the latest ceasefire will hold, but how far Turkey will go in making the Syrian opposition accept what comes next, should the peace talks jointly sponsored by Russia and Turkey take place within the next month as officially scheduled.

Indeed, even if the ceasefire fails or if the talks are unsuccessful - or not held at all - Turkish policy towards Syria is set on a new path.

For the Syrian opposition, in particular, what comes next is more of a threat than a challenge.

Yezid Sayigh is a Senior Associate at Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut.

- Published29 December 2016

- Published14 December 2016

- Published30 September 2016

- Published21 December 2016

- Published2 May 2023