Syria conflict: The biblical river at the heart of a water war

- Published

The Barada river runs through the heart of Damascus

The flashpoint for Syria's war, six years old this March, has in recent days taken the form of an elemental struggle over water.

The drinking water supply to some 5 million residents in the Syrian capital, Damascus, was cut on 23 December by the Damascus Water Authority, who say rebels have contaminated it with diesel. Rebels deny this, saying bombing by the government has damaged the infrastructure.

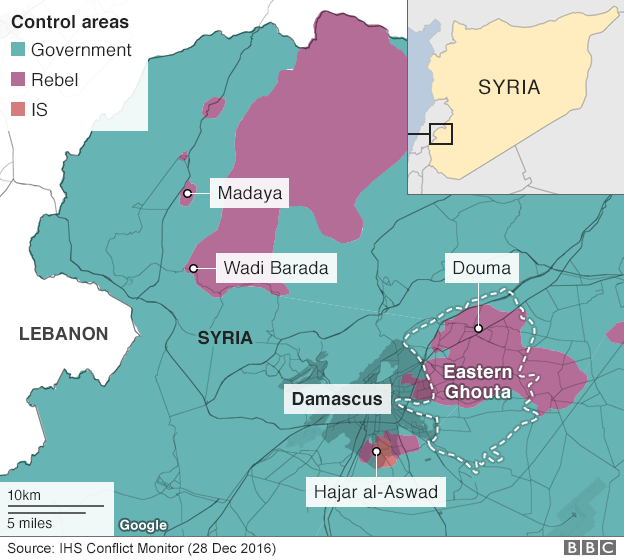

The historic water source of Ain al-Fijeh lies in the valley of Wadi Barada, 18km (11 miles) north-west of the capital, where a cluster of 10 villages has been under rebel control since 2012.

Local people joined the revolution early on in protest against government neglect, corruption and land grabs made legal under new state land measures, where whole hillsides were requisitioned for sports clubs and luxury hotels.

Both sides have blamed the other for damaging the water supply

Water provision to Damascus has been drastically reduced

On 22 December the Assad government, using barrel bombs dropped from helicopters and supported on the ground by Lebanese Shia militia fighters of Hezbollah, began a campaign to take control of the strategic valley and springs.

The timing was significant, just days before the announcement of the countrywide ceasefire brokered by Russia and Turkey on 29 December.

Network of waterways

The Barada Gorge was cut through the Anti-Lebanon Mountains eons ago by the Barada river, which still runs through the centre of Damascus.

Today the river is just a shadow of its former self, diminished for most of the year by drought and pollution to a dirty trickle by the time it reaches the city centre.

But in earlier times it was the source of the city's legendary fertility, and the reason for its location in an oasis of gardens and orchards known as the Ghouta.

A Roman aqueduct system still exists alongside the river

The river was and still is fed by the meltwaters of Mount Hermon, Syria's highest peak. Mentioned no less than 15 times in the Bible, it retains its snow-capped summit till early June.

The amount of snowfall in winter is a direct indication of how much water Damascus will have throughout the year.

The Barada river, known in ancient times as Abana, was supplemented through seven further rivers whose course was diverted by means of elaborate channels constructed as far back as the Roman era.

Guided by aqueducts into the centre of Damascus, the city was fed by a complex network of waterways and channels that allowed water to flow in and out of every house.

Sophisticated Ottoman water distribution points throughout the city also allocated water in agreed quantities to the public bathhouses, mosque ablution areas and public drinking fountains.

Even today most houses have a special drinking tap in their kitchen directly connected to the spring.

Coffee houses

In high summer families would come to Wadi Barada on Fridays and holidays, often renting a riverside platform for the day.

Rigged up as tent awnings open only onto the river side, they formed an idyllic private arbour where families could relax, enjoying the coolness of the fast-flowing river.

Little iron ladders were fixed onto the platforms, so that children could climb down and swim.

A swimming platform and ladder used by picnicing families along the river

In the 16th Century it was along the banks of the Barada river on the outskirts of Damascus that the first coffee houses grew up.

Pilgrims would assemble, waiting for the annual Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca to set off in one huge joint caravan, protected in numbers from raiding desert tribesmen.

Many engravings from the 19th Century show scenes of coffee houses on the banks of the brimming Barada.

Latin inscriptions

Near the village of Souq Wadi Barada, huge gaping holes in the cliff above can be still be accessed.

They are part of the original Roman water system: elaborate tunnels cut into the rock, conducting the meltwaters into the aqueducts of Damascus.

On sections of the old Roman road between Baalbek and Damascus, inscriptions in Greek, the official language, and in Latin, the language of the soldiers, can still be seen, describing how the road was rebuilt higher up to avoid destruction by flooding.

Latin inscriptions can be seen at the side of the road above Wadi Barada

For Hezbollah too the battle is a geographical one. They regard this area as their backyard, connected to their Baalbek stronghold in Lebanon.

The Syrian government claims there are fighters from the al-Qaeda-linked Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (formerly Jabhat al-Nusra) present in Wadi Barada, to justify its ongoing campaign. Local residents insist there are only Free Syrian Army moderates.

Since both UN monitors and Russian officials have been denied access to the area by Hezbollah checkpoints, the truth remains hidden - as so often in Syria - behind the fog of war, or in this case, beneath the waters of the Barada.

Wadi Barada and villages in the valley

Diana Darke graduated in Arabic from Oxford University and is the author of several books on Middle East society, including My House in Damascus: An Inside View of the Syrian Crisis (2016). Follow her on Twitter, external.