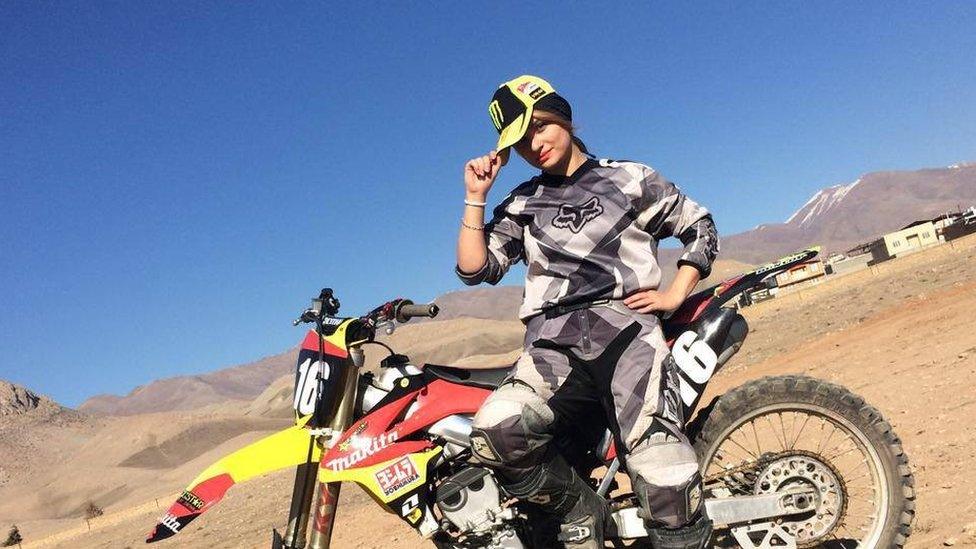

Behnaz Shafiei: Iran's trailblazing female biker makes history with women's race

- Published

After a three-year campaign, Behnaz Shafiei has been granted permission for her race

When Behnaz Shafiei crosses the finish line on Friday at the end of a dusty, rock-strewn race track in Karaj, near Tehran, it will mark both the end of a simple motorbike race and the culmination of a tireless campaign for women's rights in Iran. Whether she wins the race or not, it's a victory.

After three years of trying, the 27-year-old has won a concession from Iran's sports ministry to stage the country's first ever all-female race, despite women being barred from motorbike riding by modesty laws.

Fifteen racers will nose their front wheels to the start line, drawn from 30 applicants. As with many firsts, there won't be much of a fanfare to herald it, or possibly much of an audience. Men will be barred from the race track for the duration, by order of the sports ministry.

"This event is being handled only by women, from the organisers to the spectators to the racers," said Behnaz, down the phone from the track in Karaj, "and God willing, tomorrow it will take place".

But the risks across the country are real. Just last week, two women were arrested in the city of Dezful after being filmed riding a motorbike. Police accused them of committing an "obscene act".

And when Behnaz returns home from the track, after the dust has settled, it will still be illegal for her to ride her bike on the streets. Not that she ever really let that stand in her way.

Behnaz's obsession began at 15, on a family holiday in Zanjan in northwestern Iran where she was shocked to see a woman on a motorbike for the first time. She asked for a go and that was that, she was hooked.

In the relative quiet of the Atashgah mountains, in Alborz Province where she grew up, Behnaz could train in peace on her brother's bike. When she first ventured on to the streets, a few years later, she rode in secret, clad head to toe in helmet and leathers so no one could see she was a girl.

"You know how, when you tell a child not to touch something that's hot, she just wants to touch it more to check? Same for me," she said. "Riding my motorbike seemed to me like a pretty normal thing for a woman to do. When I saw how people reacted with shock... it just spurred me on."

It wasn't until Behnaz approached Iran's sports ministry that she realised women were banned from competing. "So I asked myself why, why shouldn't women be allowed to race? And there was no good answer."

Most of the opposition came from men, she said. "They kept telling me to go back to doing the washing and cooking. They said that women did not have what it takes to do this. That just made me more difficult, more determined to prove them wrong."

She got a green light first to practise on off-road tracks, then later to compete in men's races. The sports ministry took pains to remind her she would have to wear a hijab, she said. "Then they realised motorbike riding has a better hijab already than most sports."

But the ministry complained the hijab was not correct, so the women demonstrated to them how it was being done properly. The ministry said motorcycling was not a sport for women, so they raised the number of female participants to show it was popular. They wrote letters, they paid visits. Three years later, the ministry relented and authorised the race.

It snowed on Thursday in Karaj, covering the race track in a blanket of white. The conditions were seized on by men who wanted the race cancelled, Behnaz said.

"There are a lot of people trying to throw a spanner in the works, but the women are so determined. They picked up shovels and cleared the tracks. They mopped up the leftover water. They placed the tyres around the track - one by one and by hand - in the freezing cold.

"Every single one of them was determined that this race would take place."

Women in and around sports is a sensitive issue in Iran. Participation is on the rise, although separation of the sexes and female clothing regulations are strictly enforced. Efforts to increase equality still face stiff opposition from religious hardliners.

Women are often barred from watching men compete. President Hassan Rouhani pledged before his election in 2013 that he would loosen certain social restrictions, and in 2014 his government announced plans to allow women to watch certain men's sporting events.

But there was controversy, and protest, in Tehran in 2015 when women were banned from the stadium for a tie between Iran's hugely popular men's volleyball team and the US.

It never occurred to Behnaz not to stick at the sport she adores. "I'm persistent and I pursue the things I love, so I pursued it," she said. "And finally I succeeded." That success will be on show later when 15 back tyres kick up dust. It's the first step, she said.

"The fact that this race will be held shows that women's rights have been respected and we have achieved our demands. Not at a very high level yet, but at least we're doing something, and this is just the beginning."

Next on her personal list is a trip to the US, where she's been invited to race by a fellow female professional. She travelled to the US embassy in Dubai earlier this month to obtain a visa, but on the day she returned to Tehran US President Donald Trump announced he would temporarily ban anyone from seven mostly-Muslim countries, including Iran.

"That has left me in limbo," Behnaz said. "But I hope after this thing has passed I can reach my goal."

First things first, though: she's not sure she'll win on Friday. "From what I have seen of the girls' enthusiasm and training I don't think so. I may even come in last!", she said. But she's got a point to prove, all the same.

"You know, in Iran, women's driving skills are always ridiculed. But these same men who claim to be excellent drivers would be too scared to even watch the things I can do on my motorbike."

Majid Afshar contributed to this report.

- Published26 January 2017

- Published22 January 2017