Islamic State leaves trail of destruction in Syria's Palmyra

- Published

Lyse Doucet surveys the damage to Palmyra's Roman-era theatre

Fariha remembers the exact moment when Islamic State fighters shattered her life in Palmyra.

"It was a quarter to five in the morning. We were asleep and heard a knock on the door," she tells me as we sit on thin, grey mattresses in an abandoned school in Homs, 160km (99 miles) from her home.

This makeshift shelter, in the ruins of a Homs neighbourhood, is a refuge for her and five children, as well as 29 other families, who fled the brutal rule of so-called Islamic State (IS).

"They shouted at me to cover myself then entered my house, weapons in hand, and took away my husband and niece," she recalls as her little ones huddle close, listening, wide-eyed and silent.

Her 15-year-old nephew and her brother-in-law were also taken at that fateful time when IS first stormed Palmyra in 2015. They had their throats cut.

"They killed a lot of young men," Fariha adds, in her softly-spoken story of unspeakable savagery.

Dark chapter

As IS loses ground in northern Syria, more and more gruesome accounts are emerging of their catalogue of crimes.

IS militants have destroyed large parts of the historic site

Damage to the Roman-era theatre is clear to see

Families like Fariha's suffered twice over when IS lost, and then recaptured, the Roman ruins of Palmyra and the adjacent city.

Now, after a second occupation, lasting only three months, the area was seized a few weeks ago by Syrian forces, bolstered by the blistering firepower of their Russian and Iranian allies.

Palmyra's deserted buildings now yield evidence of its dark chapter.

The same small word

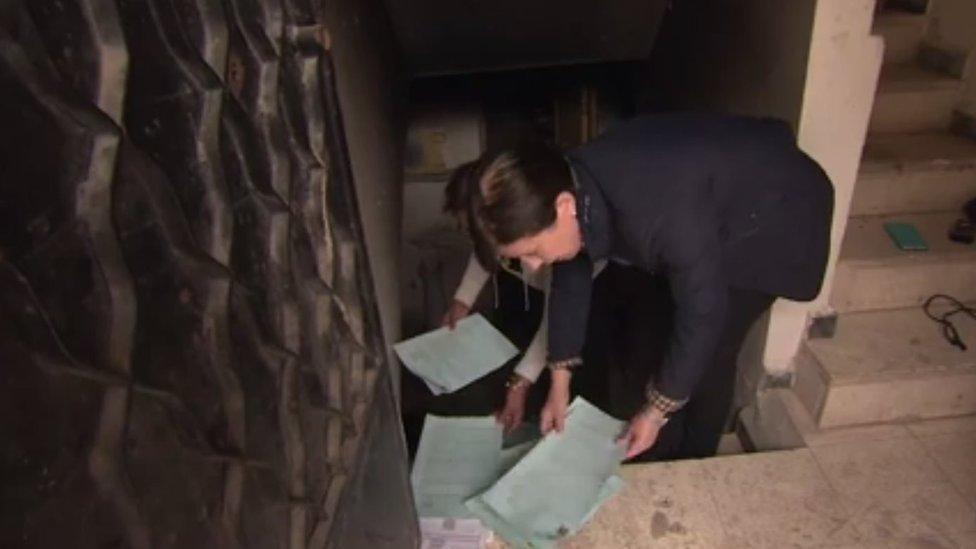

In the blackened basement of one villa, Syrian soldiers show us what they describe as a makeshift court room.

Lyse Doucet examines Islamic State paperwork condemning people to death

Mounds of blue files strewn across the floor are a measure of IS's scales of justice.

On one file after another, there's the same small word scribbled in Arabic: "qatl" - executed.

It was the fate of a woman named Farizha for "spreading corruption on earth".

Marwan met the same end for "turning from Islam".

Others faced floggings or fines.

Two men, both named Ahmed, were sentenced to be "thrown off the top of a building". No reason is listed on their joint file.

A sheet of paper taped outside the door, stamped with an IS seal of authority, notifies "everyone who lives in this state that they must enrol in a course to learn about Sharia law".

"Everyone who doesn't will be punished."

Ghost town

IS rule is over here. But with homes destroyed, and without electricity or water, Palmyra still isn't a place fit to live in, or safe to return to.

Now both ancient and modern Palmyra are ruins.

The modern part of Palmyra is also in ruins

What was once a vibrant community of 75,000 is now an eerie ghost town. Charred buildings peppered with bullet marks and gaping holes scar every street.

People fled not just IS persecution but an urban battlefield including ferocious bombardment by Syrian and Russian warplanes, which flattened multi-storey buildings into stacks of concrete pancakes.

Palmyra's pain did not start or end with IS occupation. Its prison, known by the city's Arabic name Tadmur, was a symbol of torture and summary executions long before Syria's uprising began six years ago.

Syrian soldiers now go house-to-house searching for explosives and booby traps. Russian troops, camped on the outskirts of the city, are helping to demine the area.

'Revenge for the concerts'

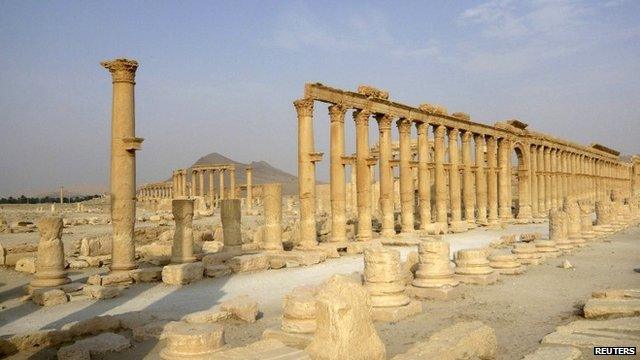

The site of the ancient Roman city nearby stands as a stark tribute to Palmyra's survival.

Despite the destruction of iconic structures such as the 2,000-year-old Arch of Triumph, Palmyra's elegant colonnaded street and striking symmetrical designs are still breathtaking.

The legacy of IS in Palmyra casts a long shadow

IS's return had bestowed a second chance to destroy more precious world heritage, but much of these monumental ruins still stand.

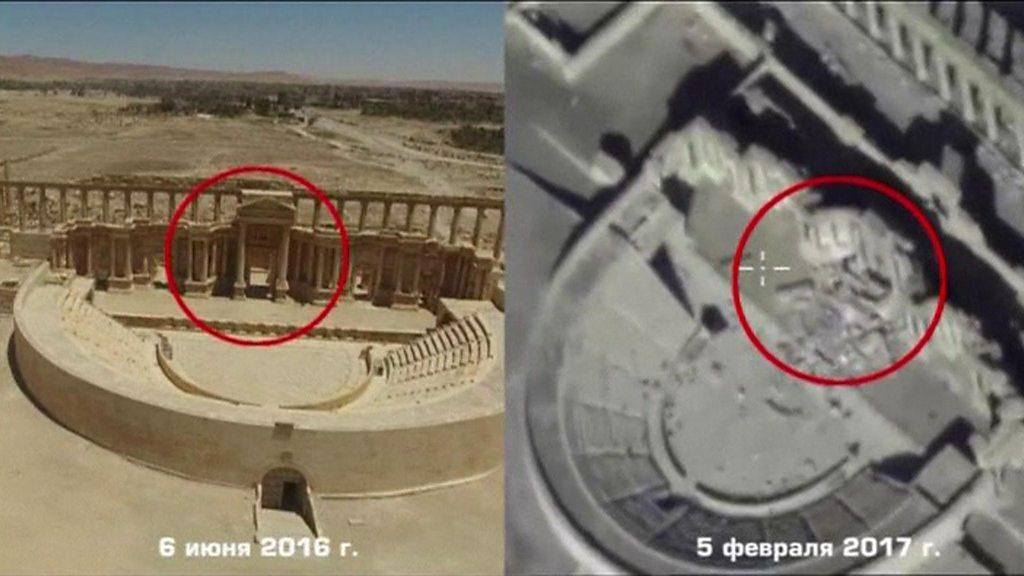

The circular Roman theatre was their prime target in January. Its imposing centrepiece, a carved facade, was smashed, leaving a jumble of jagged stone boulders on its ancient stage.

"This was their revenge for the concerts staged here by Russia's Red Army Orchestra as well as Syrian orchestras," explains a government official, who accompanies us to the site.

A dusty pile of glass candle holders wrapped in netting, and red plastic roses caked with dirt, are still tucked in some corners - mementos of the triumphal events in May 2016 when IS was defeated here the first time.

There is still evidence of the celebrations after the first defeat of IS

"Recapturing Palmyra the second time was relatively easy," says Syrian officer Colonel Malik who fought in both rounds. "The battles were more ferocious the first time."

Palmyra last fell into IS hands in December as the Syrian military was distracted by the last stages of the brutal battle for Aleppo and IS's ranks were reinforced by fighters fleeing frontlines in Mosul, crossing the border from neighbouring Iraq.

"I don't think we face the threat of losing Palmyra again," Colonel Malik tells me confidently as we stand outside the walls of the grand theatre.

"We've retaken the military airport nearby and the mountains, a space of nearly 70 sq km in less than a month, which proves IS is weakening now."

Dangerous political turf

But harder battles, including an assault on IS's self-declared capital in Raqqa, still lie ahead.

Confronting IS in their Syrian lair, closer to the Turkish and Iraqi borders, takes the fight onto messier and potentially dangerous political turf.

Hundreds of American special forces, backed up artillery and airpower, recently moved into this theatre of war to bolster an array of Syrian Kurdish forces, as well as Arab fighters.

Turkish troops are already on the battlefield, playing key roles over the past year in attacks on other IS-held towns.

All these commands face a common enemy, but also deep seated rivalries and shifting alliances.

The new US administration is still weighing how to balance a vital relationship with Turkey's President Erdogan while still making use of valuable Syrian Kurdish fighters Turkey sees as its enemy.

Turkey moved closer to Russia over the past year, but they're still on opposite sides of this war with Ankara insisting President Assad's continuing rule is what's fuelling this conflict.

The biggest question is whether President Trump's team, for whom fighting IS is the main goal, will now co-ordinate with Russia, which would end up strengthening President Assad's axis including Iran.

"The Syrian government's decision is to take back every inch of Syrian soil," insists Col Malik.

"Those criminals who infiltrated our country were supported by foreign countries like the US and the UK," he says, repeating the government's refrain that all rebel groups are creations of Western and Arab states. "They're supporting, not fighting IS."

The same accusation is levelled against President Bashar al-Assad by the Syrian opposition and its allies who charge him with turning a blind eye to IS's advance to bolster his narrative that this is a global war against terrorism, not a fight for political change.

The days of IS occupation may be counted, but its legacy casts a long shadow over a punishing war whose end is still nowhere in sight.

- Published13 February 2017

- Published1 September 2015

- Published1 September 2015

- Published19 August 2015

- Published21 May 2015

- Published21 May 2015